When strolling through Hviezdoslavovo Námestie, it is easy to get swept up in the square’s tranquil atmosphere and lovely historical buildings. The tree-lined, cobblestoned promenade is irresistible, while the castle in the distance beckons from its majestic hilltop setting. But suddenly, the square ends and you are standing at the side of a busy freeway. To the left, a suspension bridge crossing the Danube is capped by something resembling a flying saucer from a 1950s sci-fi film. Directly below the road is a noisy, graffiti-encrusted bus depot. Looking over the traffic to the right, you start wondering how you’re supposed to reach the castle on the other side. You wouldn’t be the first to stand at this odd collision of old and new, and wonder, “What the hell happened here?”

It is clear to anyone who has spent time in Bratislava that the ancient city straddling the Danube possesses many charms. Yet Bratislava sometimes gets brief and ambivalent write-ups in major travel guides, and tourists rarely visit the city for more than a day. One explanation for this apparent neglect is that the communists really worked Bratislava over, using it as a testing-ground for creating a model, modernised communist city. Unfortunately, this was done with a pathological disregard for the city’s rich history, and large swaths of Bratislava’s historical sections were demolished and redeveloped as the communists saw fit.

It has been said that Bratislava suffered more damage under communism than during the Second World War, and that a third of its historical centre was destroyed. Many travellers come to Europe to revel in its stunning old world charm, but sadly find much of Bratislava’s either ruined or absent entirely.

Roughly a quarter of Bratislava’s Staré Mesto (Old Town) was bulldozed in the late 1960s for a single project: the Most SNP (SNP Bridge known also as the Nový Most – New – Bridge), and the short stretch of freeway connected to it, called Staromestská. Dubbed the “UFO Bridge” for its obvious sci-fi aesthetic, it is a major artery, bringing traffic across the Danube, in and out of the Staré Mesto, while Staromestská links the bridge with the busy intersection just north of the historical centre.

To make space for this development, much of the city’s centuries-old, historical Jewish quarter was razed, including the 19th-century Moorish-styled Neolog Synagogue. The freeway itself ploughed a deep scar through the western edge of the historical centre, and now runs less than four metres from the façade of St Martin’s Cathedral, Bratislava’s largest, most historically significant church. “If [the freeway] were any closer, it would go through the nave,” noted the travel writer Rick Steves.

Although the Most SNP could be seen as practical planning, it is difficult to deny the devastating effect it had on the Staré Mesto’s history and urban fabric. The bridge and freeway clash with their centuries old historical surroundings, and an estimated 230 buildings were demolished. The freeway isolates Bratislava Castle from the original medieval centre, and it claimed half of the once bustling Rybné Námestie and nearly all of its buildings, which were as striking as any in the Staré Mesto today. Adding insult to injury, the cathedral’s foundations had to be restored to protect them from the vibrations of the traffic that rumbles constantly by.

From its inception in 1599, the Jewish quarter evolved around Židovská Street. This strip of land between the castle and the walled medieval centre was the only place Jews in Bratislava could legally live until 1848. All of the buildings along Židovská’s eastern side were demolished to make room for the freeway, while most of the buildings along its western side were replaced by modern residential structures. One of the neighbourhood’s few surviving historical buildings currently houses the Museum of Jewish Culture.

Aside from the museum, the only thing to indicate that a Jewish neighbourhood thrived here for centuries is a monument to Jews who perished in the holocaust, erected in what remains of Rybné Námestie where the synagogue stood, along with an engraving of the synagogue on an adjacent black marble slab.

So, how did the communists justify demolishing a historically significant Jewish quarter? As in much of central Europe, Slovakia was a dreadful place for Jews during the Second World War. Roughly three quarters of the pre-war Jewish population were killed, and many of the 30,000 who survived emigrated to the US, Israel, and elsewhere. By the war’s end, Jewish boroughs throughout Slovakia were largely deserted. When the communists seized power in 1948, the regime’s hostility towards Jews dealt a further blow to the dwindling population. Many of the deserted Jewish neighbourhoods fell into disrepair. In some towns one can still see old abandoned synagogues, either boarded up and languishing or re-purposed into storerooms, workshops or even art galleries. Bratislava’s Jewish quarter was similarly derelict, leaving it more vulnerable to the wrecking ball.

While many locals were not keen on flattening the Jewish quarter, the repressive regime choked off any dissent. “People were unable to protest,” says Viera Kamenická from the Museum of Jewish Culture. “Their hands were tied.” Besides, the communists preferred creating their own monuments over saving older ones that conflicted with their ideology, Kamenická added.

The communists didn’t stop with Židovská. In 1961, a towering orthodox synagogue behind the castle on Zámocká Street was levelled and replaced by nondescript retail and office spaces. A hulking, aesthetically incongruous extension was erected over the front of the Slovak National Gallery’s Water Barracks building, masking its arcaded 19th century façade and tree-lined courtyard. Bratislava’s main train station was hidden behind a characterless 1980s add-on. The list goes on.

________________________________________

This article was published in the latest edition of Bratislava City Guide , which can be obtained from our online shop.For those who would like to see it online first, you can read it for free here.

________________________________________

Even in the pre-communist 1940s, the city flirted with a plan to demolish the castle, Bratislava’s most iconic historical landmark. A fire in 1811 had left it a hollowed out ruin for more than a century, but eventually planners opted for reconstruction instead.

However, maintaining old structures requires active preservation and money. Several church-owned buildings at one end of historical Kapitulská Street appear on the verge of collapse, with sagging roofs and crumbling, graffiti-covered fasçades. These buildings, like most church-owned property, were seized by the state during communism, and neglected for 40 years. Although the buildings barely survived the regime, they may not survive the elements if the neglect continues. The church reportedly lacks the money to restore them, but seems reluctant to sell the property to developers. While saving these buildings could prove prohibitively costly, is it right to let them deteriorate? One suspects there would be no shortage of bids for this prime real estate.

Obviously, urban renewal is not exclusive to Bratislava. From Baron Haussmann carving grand boulevards out of Paris’ narrow mediaeval lanes, to American cities demolishing countless beaux-arts and art deco cinemas to make way for parking garages and strip malls, urban areas have always been reshaped and updated to serve the needs of growing populations. Unfortunately, this has often come at the expense of unique and irreplaceable historical structures. In Europe, however, there is growing interest in preserving historical areas, partly because they attract droves of money-spending tourists, eager to step back in time and escape the mundane settings of their own lives. An ever-growing list of protected UNESCO world heritage sites is proof of this.

But while today many people agree on the importance of preserving what remains of Bratislava’s historical centre, battles are currently being waged to prevent post-war communist-era landmarks, once objects of ridicule, from being torn down. One such landmark, the 1970s-era Hotel Kyjev and Tesco’s My Bratislava (formerly Prior) complex, is now considered a jewel of modern communist architecture, with its sleek, travertine marble exterior and stylish, retro-modern interior. However, when the UK-based Lordship Developers purchased the complex in 2006, they unveiled plans to demolish the hotel and adjacent buildings to make way for a vast complex of hotels, offices and retail shops. The plans were met with protests from the architectural community and general public, who pleaded with the city to preserve the hotel. But firm plans have still not been released. The hotel closed in November 2011 and the developers are apparently still locked in discussions with the city and monuments board over zoning regulations.

When contacted by Spectacular Slovakia in 2012, Lordship released a statement that read: “In our optimal vision the new site should unify all buildings at the Kamenné Námestie – the Kyjev Hotel, the shopping centre as well as new buildings. The revitalised square... must offer a mix of entertainment, services, gastronomy, offices and residential areas; each of these components is equally important in reviving the centre.”

Whether the company’s “optimal vision” will preserve the hotel’s retro-futuristic aesthetic remains to be seen, but any unification with the existing Tesco store could result in a modern Eurovea-style shopping centre in this area. It is difficult to determine where Hotel Kyjev will fit, particularly in its current form.

Maik Novotny, a Vienna-based architect and co-author of Eastmodern, maintains there are “several other buildings that have been and still are at risk of demolition or insensitive reconstruction. In some cases, [they] are difficult to adapt and expensive to maintain”. And although “appreciation of these buildings seems to have improved slightly,” given Slovakia’s economic climate, the risk still persists.

In light of this, one has to wonder whether anyone has learned from the mistakes that scarred the city in the past. With new office high rises and shopping centres sprouting like weeds, this remains a valid concern. It would be a shame for Hotel Kyjev to exist only as an engraving on a plaque near where it used to stand. Unless the city can welcome new development without sacrificing the old, the cycle of destruction will continue.

________________________________________

This article was published in the latest edition of Bratislava City Guide , which can be obtained from our online shop.For those who would like to see it online first, you can read it for free here.

________________________________________

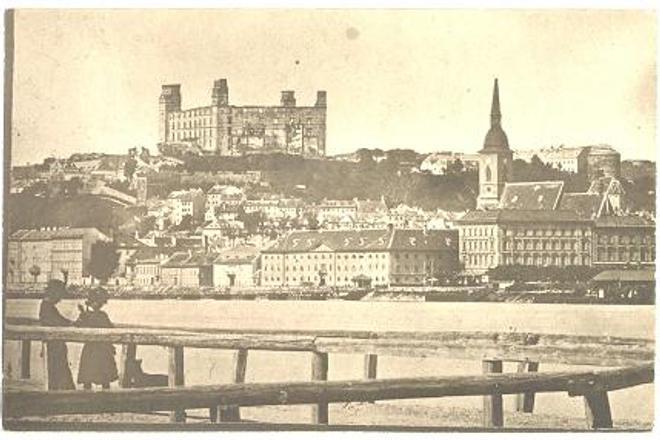

Bratislava‘s most visible historical landmark: then and today (source: Courtesy of Múzeum mesta Bratislavy)

Bratislava‘s most visible historical landmark: then and today (source: Courtesy of Múzeum mesta Bratislavy)