EXPERTS and non-governmental organisations applauded the National Programme on Combating Human Trafficking when it was approved by the Fico government in April. But those same organisations now argue that the legislation should be amended to improve documentation of cases and provide better protection to victims.

A case in point occurred this April, when Vladimír Čečot, state secretary of the Interior Ministry, while speaking at a conference on human trafficking warned that the number of cases in Slovakia was on the rise.

“Ten years ago, police recorded just three cases of human trafficking,” Čečot stated on April 3. “By 2004, it was already 27. And last year, they investigated 13.”

But a search on the Interior Ministry’s website showed that the number of reported human trafficking cases in Slovakia has actually been on a downward trend in recent years, from 19 cases in 2006 to the 13 cases in 2007.

Edit Bauer, a Slovak member of the European Parliament from the Hungarian Coalition Party, said that human trafficking cases in Europe had reached into the thousands over the years.

“In Europe, we have between one and two hundred cases annually,” Bauer told the TA3 new channel on March 31.

She also told Euractiv.sk that investigating human trafficking is not a priority in Slovakia because the public doesn’t realise it occurs here.

“But we know of thousands of children disappearing from different institutions and refugee camps [across Europe] annually,” Bauer said.

She said that the best prevention for such crimes is an approach that steps “into children’s shoes.”

“Schools need to teach children to be sceptical of promises of extraordinarily well-paid jobs, marriage, or cheap study,” she said.

Mária Kolíková, a lawyer who focuses on the issue, told The Slovak Spectator that Slovak law should be brought into accord with that in other countries.

For example, Kolíková said, Slovak criminal law doesn’t differentiate between an “aggrieved party,” which in most countries applies primarily to cases involving loss or damage to property, and a “victim,” which involves crimes that resulted in physical or psychological harm.

“We only have the concept of an aggrieved party,” Kolíková told The Slovak Spectator. “But a human trafficking victim has been more than ‘aggrieved'. They have been abused.”

Kolíková said that another problem is that authorities often will only investigate thoroughly if the person involved in the crime is willing to testify.

But Ľudmila Staňová of the Communications Department of the Interior Ministry defended Slovakia’s treatment of human trafficking victims, calling it above standard compared with neighbouring European countries.

“Our Programme of Support and Protection of Victims of Human Trafficking provides 90 days of crisis care for Slovak citizens and 40 days for foreigners,” Staňová said.

Both amounts of time exceed the 30 day minimum recommended in the Convention of the Council of Europe on Combating Human Trafficking.

Staňová pointed out that the programme is implemented in cooperation with several non-governmental organisations, which received more than Sk5 million in funding for 2008.

These NGOs include the International Organization for Migration, the DOTYK (Touch) crisis centre, the Slovak Catholic Charity, the Cultural Association of Slovak Roma, and the Prima civic association.

The programme treated 21 victims last year, and has treated 13 this year so far, Staňová said.

On the topic of the national programme approved in April, Kolíková said it shows a commitment to helping victims, but lacks specifics on how the strategy will be implemented or measured.

“The programme is very ambitious when it comes to caring for victims,” she said. “I just don’t see how to evaluate and assess it properly.”

Kolíková said another problem facing human trafficking cases in Slovakia is insufficient communication between the Interior Ministry, prosecutors, and courts as cases are shifted between their databases.

“The data they publish makes it very difficult to track the number of defendants in each case, how many were charged, and how many were sentenced,” Kolíková concluded.

She said it is also unclear when criminal proceedings begin, end, or have been decided.

But Viktor Plézel from the Presidium of the Police Corps disagreed. He said investigators, including victims' advocates, get photocopies of both the prosecution’s case and court rulings. But Kolíková responded that no database of the cases exists, which impedes research of cases and statistics.

“It would make things much easier to file cases under one base number or base file-code in one common database from beginning to end,” she said.

Justice Ministry spokesman Michal Jurči welcomed the idea of creating a common database of human trafficking cases.

“A website would help, but it is crucial to consider all the legalities that would entail,” Jurči told The Slovak Spectator. “This is a matter for police and prosecution. The Justice Ministry doesn’t have the power to do it, or access to the specifics of ongoing cases.”

Specific cases

According to several human rights organisations, victims of human trafficking are often lured by the prospect of finding well-paid work abroad. The traffickers are often close relatives. The victims are mainly women, but there are many cases involving children, and even men. The victims usually don’t report their crimes out of fear or because they need the money.

The victims are exploited either sexually or forced into slave labour. There have been reports of their organs being used for transplant, the organisations stated.

The Slovak Spectator learned the details of some specific cases of human trafficking. The names and locations in the case related below have been changed for privacy reasons.

In Gelnica, Anna K., 25, met an acquaintance, Erika M., in a pub one day to offer her a job as a maid in Italy. Erika’s husband didn’t want her take the job, but she accepted anyway because she was unemployed.

In March 2003, Anna and Erika left in a taxi for Bologna. Upon arrival, Erika was forced into prostitution. She worked 17-hour days, and was beaten several times. Clients gave her €50-100 for oral intercourse, all of which she was forced to turn over to Anna. Erika tried several times to escape, but couldn’t. Finally, in September 2003, she managed to call her husband, who immediately informed the police. After a months-long search, Erika was rescued. Anna K. was sentenced to four years in prison.

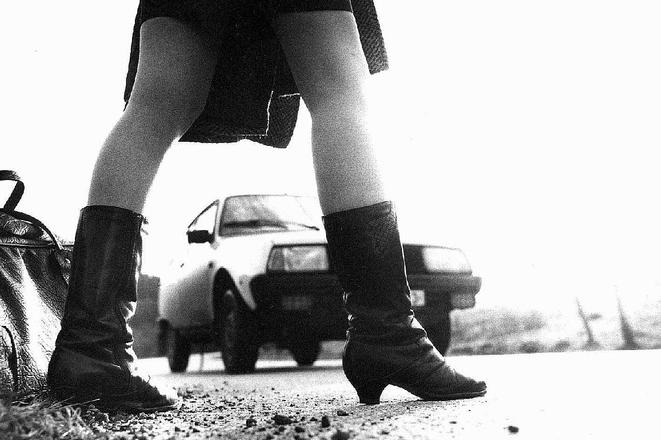

Victims of human trafficking are often forced into prostitution. (source: Sme - Ján Krošlák)

Victims of human trafficking are often forced into prostitution. (source: Sme - Ján Krošlák)