James Thomson was the author of the 14th edition of Spectacular Slovakia, published in 2009. He now writes the ‘Nice driveway!’ column for the Slovak Spectator.

‘Unknown Slovakia’ was one of the themes of the travel guide I was asked to write more than ten years ago. But even back then, a quick flick through previous editions of Spectacular Slovakia revealed that there were few places to which its previous writers had not travelled at some time (and often several) in the course of preparing the preceding 13 editions.

Partly that was because Slovakia is a relatively small place. But it was also because the guide’s writers have always been keen to uncover ‘hidden gems’ and have gone to some unlikely places trying to find them. Luckily for me, I would have to do the same.

All I want is some halušky

One cliché invariably leads to another: namely, going ‘off the beaten track’. Which sounds very romantic and exciting. On occasion, it actually is. But I didn’t have to stray very far down some tracks in Slovakia to appreciate why they were not being beaten with much enthusiasm.

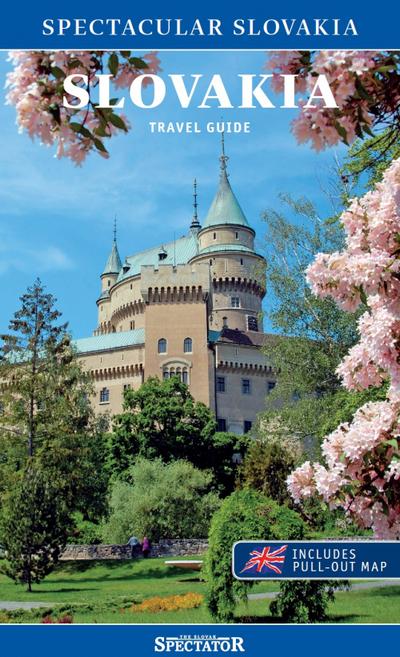

A helping hand in the heart of Europe: Slovakia travel guide.

There was the city of more than five thousand souls in the east where the only dining option on a hot summer Saturday afternoon appeared to be the less-than-enticing staničný bufet (i.e. railway station bar). Or the Low Tatras limestone cave (I have to confess, with apologies to the speleologically inclined, that these all looked the same to me) which felt justified in asking visitors to pay 300 Slovak crowns (yes, the currency was different then – this was about €10) on top of its already ambitious entrance fee just to take photos. And the village museum in Trenčín Region whose last recorded visitor had preceded me by ten months – for reasons that quickly became apparent.

Luckily, there were many more places worth going the extra mile to see: the ancient beech forests of the Poloniny National Park, on a warm summer’s afternoon, were sublime; the pretty village of Lúčka, with its Hussite church and hillside location in a valley of the Slovenský Kras (Slovak Karst) region; the East Slovak Gallery in Košice, which had just been impressively renovated but still boasted its ‘Historical Hall’ where Czechoslovakia was re-founded at the end of the Second World War; the rolling fields, dotted with vineyards, east of Levice; the ghostly remains of the Romans’ left-bank bridgehead on the Danube at Iža, near Komárno; the golden reds and yellows of the Small Carpathians in autumn.

Remembering and forgetting

Some of the locations I visited (often to the good-natured bewilderment of my local contacts) were chosen because of their recent historical significance. But occasionally I would have trouble finding anyone who knew much about that history. For instance, in a back-street plot in Veľký Meder, in southern Slovakia, lie the remains of more than 5,000 Serbian soldiers from the First World War. They were prisoners of war there, and (I was told) died in a typhus outbreak. But there was nothing to record their fate beyond a simple plaque.

The birthplace of Milan Rastislav Štefánik, Slovakia’s very own warrior, aviator, scientist, diplomat, polyglot and nation-builder, in Košariská, was unable to sell me even a postcard of the great man. (The museum was otherwise excellent, with well written and well-translated captions to the displays about Štefánik’s amazing but tragically short life.)

Some sins of omission were more troubling. For instance, I was told by a senior official at the state-funded institution whose job it is to ‘preserve’ Slovak culture that wartime leader Jozef Tiso was not a fascist. I had already learned elsewhere – from some of the excellent Slovak historians that I was fortunate enough to meet – that this was the same Jozef Tiso who presided over the the authoritarian, Nazi-allied Slovak State; who led a party whose uniformed paramilitary wing carried out massacres and reprisals against Slovaks who opposed it; and whose government stripped Slovakia’s Jewish citizens of their rights and property before deporting most of them to Nazi German death camps.

But according to this official, he wasn’t a fascist. It left me wondering quite what you had to do to qualify.

It seemed that a small but influential minority of Slovaks equated patriotism with a duty to excuse or deny the actions of the country’s former leaders, no matter how odious. Sadly, this attitude persists, and if anything such views have become more mainstream in recent years, as the presence of a nakedly neo-fascist party in parliament now attests.

As it happens, Slovakia has a fascinating and in many ways inspiring history – how many other countries can boast such a peaceful and successful transition to independence and democratic freedom? But it’s a story that few foreigners will bother to learn while Slovakia itself remains so confused about it.

Under your own power

Faced with the challenge of seeking out new places, my rather unimaginative response was instead to go to some of the old ones by novel means.

My bicycle carried me along the Danube to Komárno, along the Morava to the Czech Republic, from the Orava valley to Zakopané in Poland and, in one slightly surreal day trip, through the Carpathian foothills to Uzhhorod in in Ukraine.

The river routes were fairly easy, but even the hillier sections were manageable. I didn’t bump into too many other touring cyclists, apart from one sunburned Canadian who had ridden all the way down the Danube from Germany. There were plenty of riders cruising up and down the Danube paths near Bratislava, but outside the city I had the cycle paths and back roads pretty much to myself.

I would have liked to do more. Central Slovakia in particular has good roads, rolling hills and light traffic: perfect cycling territory. But time was short and I had people to meet.

People and places

Some of them were unforgettable.

A helping hand in the heart of Europe for you: Slovakia travel guide.

A helping hand in the heart of Europe for you: Slovakia travel guide.

The director of culture in Svidník District, in northeastern Slovakia, for example. She casually mentioned during my visit that she was leaving the next day with her folk ensemble for a festival in Makhachkala, Dagestan (!). By bus (!!). When I expressed my admiration for her commitment to folklore, she brushed off my praise as if a multi-day bus journey on some of the worst roads in Europe to one of the least stable parts of the continent was nothing out of the ordinary.

In Hronský Beňadik, in central Slovakia, the local tourist information officer, who was on a one-man mission to alert Slovaks to the historical importance of his adopted town (to wit, a rather confused tale of Roman legions, fire from the skies and heavenly intervention), presented me with a CD of his crooning (not quite as bad as I had feared) and insisted on showing me the ‘mediaeval castle’ he was building in his back garden. I assumed there had been a translation failure (our only common language being schoolboy French) – but there was the ‘castle’ alright.

Or the manager of the roadside salaš near Ružomberok who it turned out had until recently been a sommelier for Gordon Ramsay, one of London’s top restaurateurs, but had just returned to open his own restaurant.

Two wheels good, four wheels… scary

As well as cycling, I spent a lot of time in cars and buses.

Having had some experience of Slovak roads in the 1990s, it’s fair to say they had improved. However, it struck me several times during my travels that some people’s driving had yet to make a similar transition.

On the principle that it takes one to know one, and having myself taken four attempts to pass my driving test, I regard myself as something of an authority on bad driving. Yet even I had to take may hat off to the highway tailgaters, red-light jumpers and lunatics swerving through villages at 120km/h. (Curiously, the police seemed to do the same, and appeared mainly to target innocuous-looking people driving old Škodas instead of the real maniacs.)

By comparison, I was pleasantly impressed by the railways. Not all the trains were very modern, or particularly fast. But they were cheap and mostly punctual. And the scenery on cross-country trips was enough to while away the hours (alternatively, I discovered, express trains normally had a bar or restaurant car). Slovak trains have since got a bit newer and a bit faster, but have filled up with students and pensioners, who now enjoy state-subsidised free rail travel – so it’s worth reserving a seat for longer journeys.

Fun ’n’ frolics

One thing that struck me on my travels was the prevalence of aquaparks – and the billboards advertising them that seemed to litter the entire country.

If you haven’t been to an aquapark, they typically use geothermal sources to heat pools of water in which one lounges around (swimming is more for less discouraged), occasionally getting doused with jets of water which erupt from stainless steel tubes at odd moments.

It is my sad duty to report that the enticing young ladies in bikinis – or occasionally, togas – who feature in most of the advertising for these establishments were unaccountably absent during my visits.

As well as the pools, aquaparks (and spas, which have mineralised water) typically offer something called ‘wellness’. Exactly what this is remains mysterious: even the manager of one water-park admitted to me that he couldn’t really define it (though that hadn’t stopped him from marketing himself quite aggressively as a provider of it). From what I could gather, it involves saunas, massages and various other techniques designed to lighten the load on your mind and the bulge in your wallet.

Warm and filling

I like Slovak food. I’ve heard others complain that it’s too heavy or too meat-centric. Certainly, travelling widely as a vegetarian would have been difficult for anyone who was not addicted to fried cheese (happily, the situation is now hugely improved).

But I found the cuisine matched the climate very well. Meat dishes with rich sauces, bryndzové halušky (Slovakia’s national dish, a sort of potato pasta with tangy sheep’s cheese and bacon garnish) and guláš were good in winter; lighter fare like salads appeared on the menus in summer. Getting the denné menu (the daily special, normally a soup plus main course) was always a tasty, good-value option.

Coffee shops, which are now – in some places – reaching a level that might charitably be described as ‘peak hipster’, were even then a highlight. The cakes were an acquired taste (what is that stuff they use instead of cream?), but fresh palacinky (pancakes) were universally available. Now, it seems, every dietary requirement is catered for, while palacinky are less prevalent.

Menu translations were another dining highlight. Rarely very illuminating, they were occasionally startling. In one otherwise unremarkable restaurant near Nitra, I was offered ‘sweet breast of the landlady’. In the spirit of journalistic enquiry, I asked about this and it turned out to be a fairly accurate translation of the Slovak. However, none of my Slovak fellow-diners seemed to think it in the slightest bit unusual. I ordered the fish.

Get out there now

Slovakia was – and remains – an extremely agreeable country to travel around. It is perhaps even more so now: prices have risen but are still very reasonable, and tourist facilities are much improved.

There are very few places that don’t have a railway or bus station, a bit of mediaeval charm, somewhere cheap (if slightly eccentric) to stay and a good pub or restaurant. Nearby there will be a castle, a Gothic church or some more outlandish attraction (a bell museum, a giant stainless steel monument to a highway robber, a man selling cheese from a smoke-filled garden shed, etc.). And some amazing Slovaks.

Štastnú cestu! (Happy travels)

Find out more about region of folklore, national parks and modern attractions. (source: Spectacular Slovakia)

Find out more about region of folklore, national parks and modern attractions. (source: Spectacular Slovakia)

Hiking in Slovenský raj (Kyseľ Valley) (source: Lukáš Varšík)

Hiking in Slovenský raj (Kyseľ Valley) (source: Lukáš Varšík)

Bradlo (source: TASR, Robert Fritz)

Bradlo (source: TASR, Robert Fritz)

A wooden raft below Orava Castle. (source: Amanda Rivkin)

A wooden raft below Orava Castle. (source: Amanda Rivkin)

Enjoying thermal water in Nesvady. (source: Attila Molnár)

Enjoying thermal water in Nesvady. (source: Attila Molnár)

(source: Sme)

(source: Sme)