THE €42-MILLION Grandwood project to construct a wood processing plant in eastern Slovakia was seen as a life preserver to help the region combat its high unemployment. The project, however, ended before it even got off the ground, leaving behind a cloud of suspicions of attempted fraud.

Grandwood planned to build a brand new plant in the Ferovo industrial park in Vranov nad Topľou in Prešov Region. The company wanted to invest €42 million and employ 390 people over four years, and to accomplish this it sought a government stimulus worth €21.3 million, consisting mostly of tax relief, but also cash. This would have been a record stimulus of nearly €55,000 for the creation of each job. However, after suspicions emerged in the Slovak media of Grandwood making false claims about having international ties and forging a bank guarantee, the company withdrew its plans.

The company has ascribed its withdrawal from the project to a negative media campaign. Ridvan Serbes, Grandwood’s representative, announced the withdrawal in a letter to Economy Minister Tomáš Malatinský, writing that the media’s reporting of their project in Slovakia has become offensive and personal. Serbes reportedly wrote that the media had portrayed the state aid as being too high and had reported that there was uncertainty over whether the newly created jobs would remain after the aid expired. There have also been suggestions in the media that the company has close ties to the ruling Smer party and that cronyism played a role in the deal.

Ridvan Serbes is a German businessman of Turkish origin. He has been active in several companies from Switzerland, Turkey and Germany, some of which no longer operate or have gone bankrupt, the Hospodárske Noviny economic daily wrote.

A grandiose start

The project enjoyed the public support of Prime Minister Robert Fico. Directly in the Ferovo industrial park on April 16, Fico, together with Malatinský and Grandwood holding representatives, signed a memorandum between the Slovak government and Grandwood. The company’s plan was to build in the local industrial park a plant for processing lower quality broadleaf wood and production of plastic wood, especially for the ship-building industry, to be exported to Turkey, Switzerland and Poland.

The memorandum was merely symbolic, and the government postponed several times its decision to grant the stimulus after Hospodárske Noviny pointed to some discrepancies. The daily pointed out, for example, that the Grandwood limited company was launched only in 2011, i.e. shortly before it applied for the stimulus, with its headquarters listed at an address of an apartment building in Košice, and that it had yet to conduct any actual business. Grandwood stated that it belongs to the big Turkish business group Yesim Tekstil, which subsequently denied the claim.

According to the daily, Grandwood might also have fabricated a letter sent by the British bank HSBC to Slovakia’s Tatra Banka, in which HSBC reputedly confirmed that they were prepared to provide a €50 million bank guarantee to Grandwood that would serve as a guarantee towards Tatra Banka in the event that Grandwood failed to settle its obligations to Tatra Banka. HSBC told Hospodárske Noviny that they did not send any such letter. The state investment agency, SARIO, also had doubts when scrutinising the details of the planned investment, the Sme daily wrote.

The opposition party Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) filed a complaint in early May, citing suspicions of subvention fraud.

The ministry’s refusal to grant the stimulus to the company is not enough, SaS deputy Ľubomír Galko told Sme, adding that “if it is true that somebody deliberately cheated, he should bear criminal liability”.

Grandwood, as well as the ruling party Smer, argued that the company applied for the state stimulus during the term of economy minister Juraj Miškov from SaS, who green lighted the plan, Sme wrote. SaS responded that at that time the ministry gave the company a letter of acceptance because it satisfied the conditions.

Subvention fraud in Slovakia

Grandwood was not the first time the Slovak government fell for such bait, Sme wrote. In June 2006, one week before the parliamentary election, then prime minister Mikuláš Dzurinda introduced in Spišský Hrhov in eastern Slovakia the fourth most important investment in the post-revolution history of Slovak industry. The investor, Akermann, promised to build a factory for SKK16 billion (approximately €530 million) which would bring 1,000 jobs, and asked the state for stimuli worth SKK800 million (approximately €27 million). The company was supposed to produce car parts from composite materials. After some months the government realised that this was a case of attempted fraud and did not give a single crown to the company.

Fico ‘produced’ a similar embarrassment this year in Vranov nad Topľou, according to Sme.

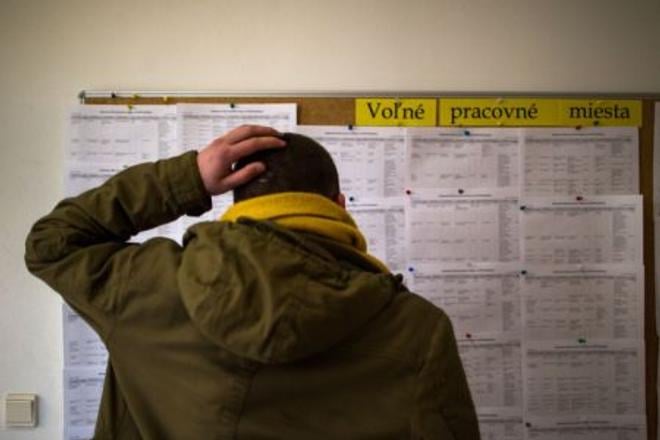

Jobless Vranov nad Topľou

Vranov nad Topľou, like all of Prešov Region, suffers from high unemployment. In the district of Vranov nad Topľou, April’s jobless rate was 24.74 percent, the seventh worst in Slovakia, and 20.52 percent for the whole region of Prešov. April’s national jobless rate was 14.41 percent, according to the Central Office of Labour, Social Affair and Family.

The town built the Ferovo industrial park with the help of EU funds, but it remains empty despite having been looking for investors for four years. The town needs investors who will bring to the park at least 700 new jobs, otherwise it will have to return the €4.3 million in EU funds which they used for the park’s construction, according to Hospodárske Noviny.

Experts see the failure to attract investors and the lack of infrastructure as behind the high unemployment in Vranov nad Topľou.

Luboš Sirota, chief executive of McROY Group, a Slovak recruitment company, says the problem with Vranov nad Topľou is that the region failed to attract investors during the investment boom 10 years ago and that nowadays it is more difficult to find investors for such regions, according to Sme.

Tibor Gregor from Klub 500, an association of companies with more than 500 employees, considers the unfinished highway across Slovakia to be a major obstacle.

“The investor will not go where it does not have a highway and has no guarantee that the truck will arrive on time and will be able to transport its products on time,” Gregor told Sme.

With press reports

The ÚPSVaR changed methodology to report the jobless rate. (source: SME)

The ÚPSVaR changed methodology to report the jobless rate. (source: SME)