You can read this exclusive content thanks to the FALATH & PARTNERS law firm, which assists American people with Slovak roots in obtaining Slovak citizenship and reconnecting them with the land of their ancestors.

In Germany, where he used to work on construction sites, Jaroslav Lechan realised that what he really loved was traditional crafts, and that he no longer wanted to leave his family in eastern Slovakia for a long time.

“I earned money, but I did not see my family,” the Slovak recalls of the bygone days.

When he returned home, to the village of Topoľa, Snina District, he found a job at a warehouse. Lechan knew that it was not a dream job and began to toy with the idea of starting his own business. Because he grew up on his grandparents’ farm and knew different traditions and crafts, he had a clear vision of what services he would want to offer to people. With a little help from the European Union, he eventually turned the vision into reality.

Lechan opened his own centre of crafts in Topoľa a few years ago. There, he bakes bread in a clay oven, make ceramics, and even teaches visitors how to build a thatched roof or rake grass. He also runs a sheep farm and provides accommodation in the attics of two houses owned by his family.

“A tourist usually enjoys luxury at home, here they do not need any TV in their room,” says Lechan. “What they need is peace, connection, and time in the forest.”

Topoľa is set in the Poloniny National Park, the easternmost Slovak national park. This preserve is known for its primeval forests, some of which are inscribed onto the UNESCO list, but also for the European bison and its dark skies (You can learn more about the far-flung area in our Spectacular Slovakia travel guide.).

But unless visitors from abroad or western Slovakia have a car, it may be a challenge to reach the national park and villages nestled in it. The railroad ends in the village of Stakčín. Then, only infrequent buses will take visitors to the village of Nová Sedlica, where many visitors start exploring the national park. Nová Sedlica and Stakčín are less than 40 km apart, and somewhere in between can be found Topoľa.

Local people, too, say that the region, which is squeezed in between the national park and the Vihorlat Mountains, is hard to access, making it almost impossible to develop local tourism. Still, Lechan and a handful of mayors and local entrepreneurs are living proof that things can change for the better if there is the will to do so.

National park is an opportunity, but also a burden

Despite being part of the EU for 20 years, Horný Zemplín (Upper Zemplín), a tourism region across which Poloniny spread, has been struggling.

In the village of Ulič, a stone’s throw from the Slovak-Ukrainian border, a furniture company had gone bankrupt even before Slovakia joined the EU, in 2004. It took the village a long time to recover. Today, Lesopoľnohospodársky Majetok Ulič, a state-owned forestry company and the major employer in the region, is limiting activities in cattle-breeding, growing crops, and logging in order to enhance nature conservation. Nevertheless, this has resulted in job cuts.

For the past two decades, local people in Ulič have been leaving their homes to work elsewhere, not just the jobless but also those who felt underpaid at the forestry company. They have gone to Bratislava, the Czech Republic, but also to Germany. Snina, one of the major towns in the region, was not an option for them.

“Salaries are low there,” sighs Ulič mayor Ján Holinka.

Some locals also feel that the expansion of the national park is unjust because it limits their forestry jobs, making earning a livelihood next to impossible. They cannot log wood wherever they would like to, and they have not yet learned to benefit from tourism, except for a few exceptions.

And then, there are people like Lechan who have returned to their home, to the Poloniny area, from abroad with saved money. They are not interested in farming but in tourism or other businesses.

“Young people avoid farming due to hard work and a lack of land,” the Ulič mayor thinks. “Instead, they are building or repairing private accommodation for tourists.”

Seven smaller hostels, each providing around 20 beds, were okayed last year, Holinka adds.

However, tourism in Slovakia has long faced obstacles in many forms, including strict legislation and poor infrastructure. Some of the local people underscore that building a guest house in a village without access to water supply and sewerage during summers is challenging. The nearby Starina water reservoir does not supply water to the surrounding sparsely populated villages due to high costs. Instead, water flows west, to the major eastern Slovak cities of Prešov and Košice, not to the east.

Inspiration in Poland

Poloniny National Park borders Bieszczadzki National Park in Poland. The Ulič mayor, who often visits Poland, believes that Slovak people can learn a lot about how tourism should be done from the Poles. As he points out, Slovakia has been discussing reviving tourism for 20 years, whereas the Poles have actually taken action, built the necessary infrastructure and improved their services.

“The changes on the Polish side are evident at every turn,” Holinka asserts.

In Poland, where the government tightened the protection of forests, he explains, the government also helped people living near a national park affected by such changes. In Slovakia, Holinka paints a different picture.

“With the new zoning plan for Poloniny, some of the forests that had previously belonged to people were taken by the state, which then put them under strict protection, without any form of compensation,” Holinka says, adding that some people were furious. According to him, it is imperative to establish precise regulations that will clearly define the areas that will be protected, the routes of bike trails, and the areas where guest houses will be permitted to exist.

Ján Kepič, the mayor of Zemplínske Hámre, also agrees that Poland has less strict legislation, making everything easier compared to how things are done in Slovakia. According to him, Slovakia possesses a five-stage control procedure for the utilisation of European funds, which can be detrimental to certain projects due to a lack of sufficient time for completion. The unnecessary bureaucracy is a significant issue. Kepič cites the example of a tourist train project, which he has been working on since 2019. He still has not completed all the necessary paperwork.

Historical names of towns and villages in Snina District

Slovakia's territory was part of different monarchies throughout the history, including the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1867 until 1918. Until 1992, with the exception of the inter-war years 1939-1945 during which the Nazi-aligned Slovak state existed, the territory was a part of Czechoslovakia. As a result, the current names of Slovak municipalities were different.

Here's a list of the largest municipalities in Snina District with their historical names stated in the brackets:

Snina (Szinna)

Belá nad Cirochou (Cirókabéla)

Dlhé nad Cirochou (Cirókahosszúmező)

Kalná Roztoka (Kálnarosztoka)

Pichne (Tüskés)

Stakčín (Takcsány)

Ubľa (Ugar)

Other villages mentioned in the story:

Zemplínske Hámre (Józsefhámor)

Ulič (Utcás)

Topoľa (Kistopolya)

Osadné (Telepóc)

Runina (Juhászlak)

Pčoliné (Méhesfalva)

The full list of all Slovak municipalities, including their historical names, can be found at www.geni.sk (in Slovak only).

The fact that Polish people are more entrepreneurial is confirmed by Eva Kocanová from the local civic association Také Naše (Ours). “They are not ashamed to offer services to visitors and get paid for them. With a little invention, we can do it too,” she says. Kocanová also underlines the difference in land ownership. Despite the fact that Bieszczadzki National Park holds ownership of the land it intends to develop, facilitating the construction of tourist infrastructure by Poles, the land in Slovakia remains fragmented.

Gastronomy can attract tourists

Despite challenges, local entrepreneurs in the Poloniny area have established new companies, which is a good sign for the future of this corner of Slovakia.

Two women in Ulič began cooking "tatarčane" pirohy, also known as pierogi, 15 years ago. Today, their company, Hany Ulič, employs around 20 people. The pierogi are named after buckwheat flour, called tatarka in eastern Slovakia. Hany Ulič produces several tons of pierogi a month. The firm supplies them to various shops and restaurants.

Ten years ago, Juraj Kovaľ, the son of one of the founders of the pierogi company, and his childhood friend Miroslav Telehanič, who worked as a bartender, started their joint business - natural syrups produced from local ingredients. Telehanič had been bothered by the fact that syrups for mixed drinks contain only artificial flavours. He convinced Kovaľ to make syrups without preservatives, chemicals, artificial flavours and colours. Kovaľ, a teacher by profession, was excited about the idea, and thus they started their business in Ulič.

After initial attempts at cooking syrup in their parents’ kitchen, their products caught on in the market. They gradually began working with more fruits and flavours.

Today, they have suppliers from all over Slovakia. They also buy non-traditional fruits such as sea buckthorns and chokeberries from local growers. Three years ago, they started planting their own berries such as gooseberries, currants, blueberries and raspberries. In addition, they plan to build greenhouses for herbs.

“It is like a nursery. We can find out which bushes do well in this area, and then we will plant them in large numbers,” says Kovaľ.

They call their syrups “vlčie” (wolf) because they are directly from the Wolf Mountains, as the Poloniny are nicknamed.

The mayor of Ulič believes that Poloniny has potential as a tourist destination, particularly when it comes to the Rusyn cuisine. A minority in the country, the Rusyns are a distinct Slavic group from the Eastern Carpathians living in northeastern Slovakia.

The mayor recalls a recent visit by French tourists who were more interested in people, traditions, culture, wooden churches, and gastronomy than in forests. According to the mayor, these visitors saw the national park as an opportunity to experience the local culture and not just the natural beauty of the region.

No second Tatras, please!

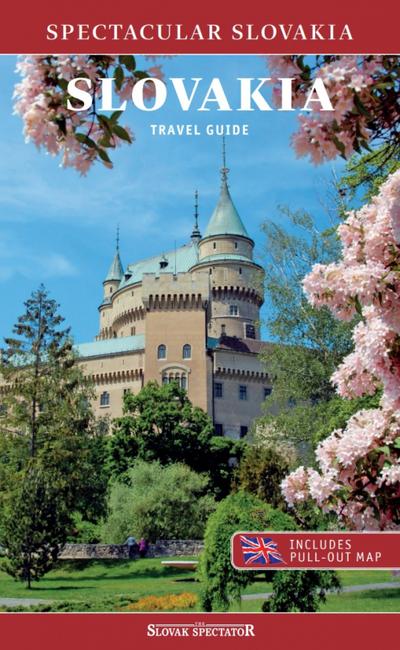

A helping hand in the heart of Europe offers a travel guide of Slovakia. (source: Spectacular Slovakia)

A helping hand in the heart of Europe offers a travel guide of Slovakia. (source: Spectacular Slovakia)

Several local entrepreneurs approached by The Slovak Spectator believe that the best years for tourism in Poloniny were during the coronavirus pandemic. Since then the number of visitors has decreased, and the region still does not see enough tourists to rely solely on tourism.

Tourists often mention that they enjoy the natural beauty of the area but lack services and other attractions, Kováľ notes. After three days of visiting, tourists have nowhere to spend their money, according to him.

Only a small share of tourists are interested in spending a week in the woods. However, if the locals wish to attract more regular tourists, they will have to find a way to provide additional entertainment options, say, for families with children. These families are not interested in hiking every day and therefore, they need other child-friendly activities.

However, Kovaľ thinks that Poloniny should not be transformed into a tourist destination similar to the Tatra Mountains, which are full of hotels, ski resorts and attractions.

“To attract more tourists, we must offer something unique while respecting nature. Tourism is on the right track, but it will take another 10 years to develop,” he adds.

Boris Ocetník, an innkeeper in Osadné, shares a similar opinion. In his opinion, the best era in Poloniny ended with the pandemic, when people travelled around Slovakia instead of abroad during the summer.

“Thousands of tourists a day will never visit this place, but hundreds will come for sure,” he says.

Unlike the supporters of soft tourism, the innkeeper believes that the region could benefit from constructing at least one top hotel, which could attract more demanding guests in return. He acknowledges, however, that in order to attract more discerning visitors, a more robust system of support and improved access to Poloniny are essential.

The mayor with big plans

Twenty years ago, Zemplínske Hámre, near Snina, was just a small village. Apart from a grocery shop and a pub, there was nothing much to see or do. However, the village was fortunate enough to have some forward-thinking mayors who decided to revive the village’s iron-making past and attract tourists.

They obtained European funds for their projects showcasing the history of iron ore mining in the village. Today, a museum operates in Zemplínske Hámre. There is an educational trail in the village, where visitors can learn more about the history of the long-gone ironworks.

Ján Kepič, the current mayor, has revived unused routes along the former narrow-gauge railway, which had been previously used to carry iron ore. The new asphalt cycle paths have replaced the old railway tracks. In addition, Kepič says that he plans to connect Lower Zemplín (Dolný Zemplín) and Upper Zemplín regions via the Vihorlat Mountains using cycle routes. Although it takes 72 km to drive around the mountain range, it takes only 17 km to the village of Remetské Hámre, on the other side of the Vihorlat Mountains, if cyclists follow bike trails. However, the Vihorlat area also covers military forests, which are inaccessible to visitors, and a protected nature reserve.

Zemplínske Hámre also collaborates with local craftsmen, including Jaroslav Lechan.

The mayor’s dream is to build a cable car to Sninský Kameň, a stone formation in Vihorlat. The place offers a beautiful view. He also would like to see this cable car extended all the way to Morské Oko, one of the largest lakes in Slovakia, but he knows that conservationists may not like the project. Despite this, the mayor remains optimistic and hopeful.

“We don’t want a Disneyland or mass tourism here, but we have to offer people activities so they don’t get bored,” says the mayor.

Spectacular Slovakia travel guides

A helping hand in the heart of Europe thanks to the Slovakia travel guide with more than 1,000 photos and hundred of tourist spots.

Detailed travel guide to the Tatras introduces you to the whole region around the Tatra mountains, including attractions on the Polish side.

Lost in Bratislava? Impossible with our City Guide!

See some selected travel articles, podcasts, traveller info as well as other guides dedicated to Nitra, Trenčín Region, Trnava Region and Žilina Region.

The Lechans revived traditional crafts in Topoľa, Snina District, to attract more visitors to the region in eastern Slovakia. (source: SME-Jozef Ryník)

The Lechans revived traditional crafts in Topoľa, Snina District, to attract more visitors to the region in eastern Slovakia. (source: SME-Jozef Ryník)

Ján Holinka, the mayor of Ulič, believes that Slovak people can learn a lot about tourism from the Poles. (source: SME-Jozef Ryník)

Ján Holinka, the mayor of Ulič, believes that Slovak people can learn a lot about tourism from the Poles. (source: SME-Jozef Ryník)

Boris Ocetník, an innkeeper in Osadné, says that mass tourism never comes to Poloniny. (source: SME-Jozef Ryník)

Boris Ocetník, an innkeeper in Osadné, says that mass tourism never comes to Poloniny. (source: SME-Jozef Ryník)

Zemplínske Hámre mayor Ján Kepič has plans to connect Lower and Upper Zemplín via the Vihorlat Mountains using bike trails. (source: SME-Jozef Ryník)

Zemplínske Hámre mayor Ján Kepič has plans to connect Lower and Upper Zemplín via the Vihorlat Mountains using bike trails. (source: SME-Jozef Ryník)

Ruská Bystrá (source: Tomáš Hulík)

Ruská Bystrá (source: Tomáš Hulík)