IT NEVER promised to be an easy undertaking, even when Slovakia’s economy was described as a central European ‘tiger’. Now, with the global economic downturn taking its toll on all sectors, the cross-country highway linking Bratislava in the west with Košice, Slovakia’s second city, in the east – a project that politicians have been promising the nation since the early 1990s – is proving devilishly difficult to complete, and promises to extract much more sweat from both the state and the private enterprises involved.

The government of Prime Minister Robert Fico had originally hoped that with the help of public-private partnership (PPP) projects the state could at least get somewhere close to its earlier promise to complete the highway, excluding tunnels, by the end of 2010. Politicians stuck to this plan even after the full eruption of the financial crisis. By mid October 2009, however, it was clear that achieving these ambitions will be difficult, to say the least.

The tightfistedness of banks when it comes to lending to mega-projects, as well as higher financing costs, could throw barriers in the way of even the most realistic plans, according to observers.

Transport Minister Ľubomír Vážny recently suggested that the country will finally get the highway, with all its bridges and tunnels included, in 2014.

The highways project carries one of Slovakia’s heftiest price tags of all time: rough estimates talk about €21 billion over 30 years.

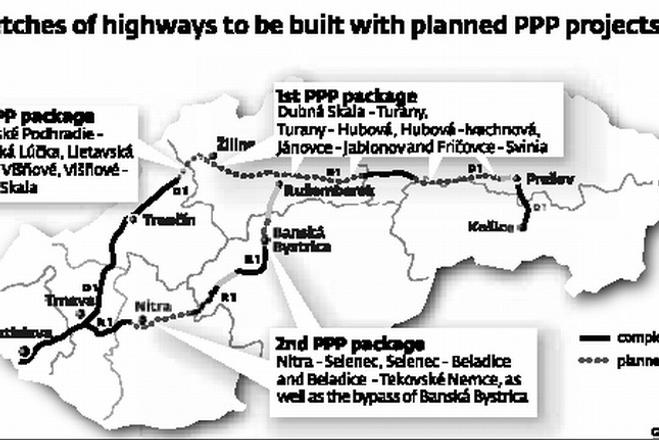

The PPP projects are supposed to cover 150 kilometres of national highways. These are to be managed in three packages: sections of the D1 highway make up the first and third packages; while construction of parts of the R1 dual carriageway in central Slovakia making up the second package.

The first package should be concluded in terms of its financing with the contractor by February 15.

In mid October the Transport Ministry said it now regards 2013 as a realistic date for completion of the sections included in this package, the TASR newswire reported. The pre-crisis completion target was 2010, excluding the more demanding tunnels, which should have been added to the completed sections by 2012.

The ministry has not yet set a date for the financial wrap-up – also known as financial ‘close’ in official parlance – of the third package, but the state still hopes to reach agreement with PPP contractors. If it fails to do this, it will have to seek money from public sources. Vážny has admitted that relaying only on resources from the state budget would be a problem.

However, the government hopes to achieve progress with the third package before the general election scheduled for next year, picking a contractor by the end of October 2009 and wrapping up the project financially by mid 2010. The second package already has a private partner and the project was financially closed on August 28, according to the SITA newswire.

On October 16, the highway plans gave the impression of having moved ahead. The construction of all five sections of the D1 highway within the first PPP package has officially started, and with it an image typical for the pre-election period: Prime Minister Robert Fico and Transport Minister Vážny laying a cornerstone for a highway tunnel near Žilina.

The construction of the 75 kilometres of the D1 highway, from Dubná Skala (near Vrútky) to Svinia (Prešov district) will be financed through the first PPP package. Fico has estimated that the costs of this package, with its four tunnels and 106 bridges, will be €2.1 billion. The state will pay approximately €4.2 billion in instalments over 30 years for the construction, operation and maintenance of the five sections.

Even though financial close is expected in February, Fico explained that preparatory works are already starting on a 35-kilometre section, at a cost of €17.8 million, according to the SITA newswire.

Meanwhile, the government on October 21 approved an additional €11.56 million from the state budget to complete the financing of the D1 highway.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) will supply €1 billion to the project while the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development will provide €250 million.

“We regard the fact that these renowned international institutions have joined our PPP projects as positive,” Irma Chmelová, executive director of business lobbying group the PPP Association, told The Slovak Spectator. “These institutions conduct their own independent audit of projects and they do not invest into projects which lack quality. Moreover, in the case of the EIB such financing allows access to cheaper resources than via commercial banks.”

The first package consists of sections of the D1 motorway Dubná Skala-Turany, Turany-Hubová, Hubová-Ivachnová, Jánovce-Jablonov, and Fričovce-Svinia.

Sections of the R1 dual carriageway – Nitra-Selenec, Selenec-Beladice, Beladice-Tekovské Nemce and the northern bypass around Banská Bystrica – make up the second package, while the third package comprises the D1 motorway sections Hričovské Podhradie-Lietavská Lúčka, Lietavská Lúčka-Višňové, Višňové-Dubná Skala, and the motorway feeder Lietavská Lúčka-Žilina.

However, the government needs to provide financial guarantees for all the packages. The economic downturn has complicated the process of obtaining funds for all three PPP packages.

“All the investment projects, be they in the private or public sphere, are influenced by the negative developments on the financial markets,” Chmelová said. “This influence is obvious mainly in the case of large projects, which require long-term investments, since the banks are unable in the current times to provide to the amounts needed and are requiring additional guarantees.”

The state has, however, decided to guarantee the loans, which Chmelová said the crisis has made a practice in other countries as well.

“Due to the crisis, state guarantees for PPP projects have become a normal phenomenon – even countries experienced in PPP such as Great Britain or France have not avoided providing such guarantees,” Chmelová said. “However the state guarantee for part of the loan does not mean that the private partner is freed of the duty to secure financing.”

According to Chmelová, in the case of the first PPP package the private investor is expected to secure 70 percent of the funds; the rest will be provided by the EIB.

Eurostat accounting rules suggest that the risk is not shifted back to the public sector if the guarantee or similar instrument does not exceed the prevailing part of the debt service, which means that providing guarantees for a smaller part does not strip the project of its chance to qualify as a full-value PPP project, she added.

“Moreover, in the case of the EIB, such financing makes access to cheaper loans possible, which in the case of such a financially demanding project as the first PPP package is an important aspect,” Chmelová said.

Meanwhile, Finance Ministry State Secretary Peter Kažimír said on October 21 that the three PPP highway construction projects will cost taxpayers €700 million a year over 30 years, starting in 2014.

“We deem it to be an investment in the future,” Kažimír said, as quoted by TASR. “It’s construction of infrastructure: it’s a necessity.”

As early as May the cabinet announced finance-related delays to the first package of PPP projects and approved an appendix on financing to the agreement, which is with a consortium led by the French company Bouygues Travaux Publics, to design, build, finance, and operate D1 stretches totalling 75 kilometres.

The ministry had signed the concession contract with representatives of the consortium on April 15.

The consortium, which as well as being led by Bouygues Travaux Public SA also includes the Slovak companies Doprastav and Váhostav-SK, set up a new company, Slovenské Diaľnice, to complete the project. The consortium’s bid for construction and operation of the D1 sections amounted to €3.3 billion.

Why PPP? What about the crisis?

According to Chmelová, an advantage of PPP projects is that they make infrastructure investments possible even during a crisis since payments are spread over several years.

The crisis has complicated most investment plans, including PPP projects, and has done so all around the world.

In PPP projects the private investor is responsible for obtaining the required funds and this is where the greatest impact of the crisis was felt: not only have loans become more expensive, but banks have become much less willing to provide large, long-term loans, said Chmelová.

For example, in the case of the second PPP package, for which financial close was concluded in late August, the early assumption was that a couple of banks would be enough to supply the funds, but in the end there were 14.

“At the same time the period of procurement was stretched due to problems that the crisis has brought,” Chmelová told The Slovak Spectator.

The second package has made the most progress so far. Minister Vážny signed a concession contract with Fadi Selwan, president of Vinci, one of the companies making up the consortium which won the tender – to construct 51.6 kilometres of the R1 dual-carriage way between Nitra and Banská Bystrica – on March 23. The consortium won the tender with a bid of €1.5 billion.

Although the first PPP project covering five sections of the D1 highway has not reached financial close, Chmelová said the risks of the project are pretty much the same as for the second PPP package, for which the concessionary contract was signed first and financial close was achieved later.

“Such proceedings are usual in the world today,” Chmelová said. “We do not see anything strange about this proceeding being applied also in case of the first PPP package. Of course, until the package is financially closed, there is a risk that the project will not attract sufficient resources.”

Only the second of the three public-private partnership highway projects is fully underway. (source: SME)

Only the second of the three public-private partnership highway projects is fully underway. (source: SME)