The showing currently running at the Slovak National Gallery (SNG) offers an exhibition of Slovak modernism which was an outgrowth of European modernism but retained some domestic specifics that set it apart.

The exhibition offers works from the first half of the 20th century, mainly from the 1920s to the 1940s which were the prime years of Slovak modernism which included paintings, works embellished with graphic artwork, and works on paper. Sculpture is also included though it was a minor genre in this movement and not very advanced during this time.

Compared to Western European modernism, Slovak works are more nationally-oriented and more topical. Only a few of the artists presented o depicted urban and social issues. As Slovakia was prevailingly agricultural at that time, many of the more famous works, especially by Martin Benka and Ľudovít Fulla, reflect the rural life and the beauties of Slovak nature.

The exhibition begins with Košice Modernism – “which offers a direct step into the most avant-garde part of the exhibit”, lecturer Zuzana Koblíšková,” said. “Typically, Košice welcomed progressive Hungarian artists fleeing to a freer – both politically and artistically – atmosphere. The works of three representatives of this group, Anton Jaszus, Konštantín Bauer and Eugen Kron are displayed. Kron tended to portray people in extreme situations, even fighting for their lives”, Koblíšková added. Bauer’s style combines Cubism and Neo-Classicism; he is one of the few who focused on people from the urban underclass, with an emphasis on “urban viciousness. Not many works of Košice modernism have survived because many of the works were destroyed by a fire in the museum.

Works of some other artists are internationally famous, including Martin Benka. This exhibition contains some of his paintings which are not typical and which represent the more poetic, more Art-Nouveau-style beginnings of his work. Later, he came to admire Slovak nature in general and the Tatras in particular. He inspired other artists to depict the myths of Slovakia as well as its beauty. Other highly-regarded painters of this period and genre include Janko Alexy, Miloš Alexander Bazovský, Edmund Gwerk and Zolo Palugyay.

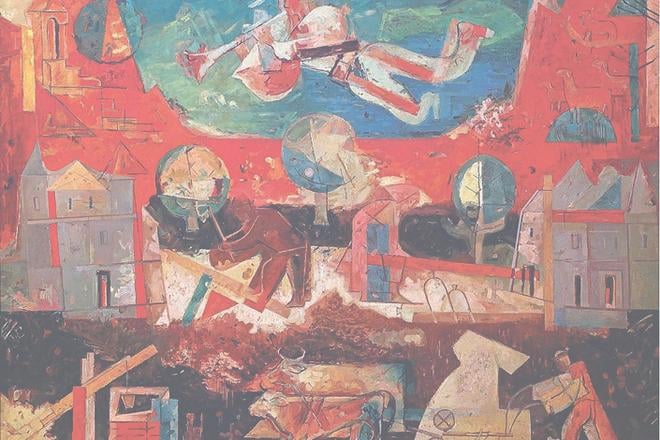

Mikuláš Galanda and Ľudovít Fulla, working with national themes, published a manifesto of modern painting – in 1930-1932 -- titled “Listy Ľudovíta Fullu a Mikuláša Galandu / Letters of Ľ.F. and M.G.” which strove to formulate requirements for modern painting in order to achieve a pure “art for art’s sake. “In his work,” Koblíšková said, “Fulla concentrated exclusively on colour and line in his series of three works made to order for a Romanesque church, called Pieseň a práca – Song and Work; and Požehnanie statku – The Blessing of a Homestead. Pieseň a práca won the Grand Prix at an international exhibition in Paris in 1937.” She added, however, that the works were so progressive that they were never installed in the church.

One room is dedicated to surrealism and to Jewish artists. Slovak surrealists exhibited in the SNG are František Malý and Imrich Weiner-Kráľ. The exhibition ends in the post-World War II period, marked by the enthusiasm and hope that prevailed after the war ended. The SNG has prepared a follow-up exhibition Prerušená pieseň – umenie socialistického realizmu / Interrupted Song – The Art of Socialist Realism that will open on June 28.

The “marginal” character of art can be an advantage, the gallery writes in its leaflet to the exhibition, as it can express “our own, domestic” version of modern art. The exhibition runs in the SNG daily, except for Mondays, until October 28. Accompanying texts are also available in English. On June 14, there will be a lecture in English on the exhibition, within the Thursday Art talk series. More information can be found at www.sng.sk.

Ľudovít Fulla: Song and Work. (source: Courtesy ofSNG)

Ľudovít Fulla: Song and Work. (source: Courtesy ofSNG)