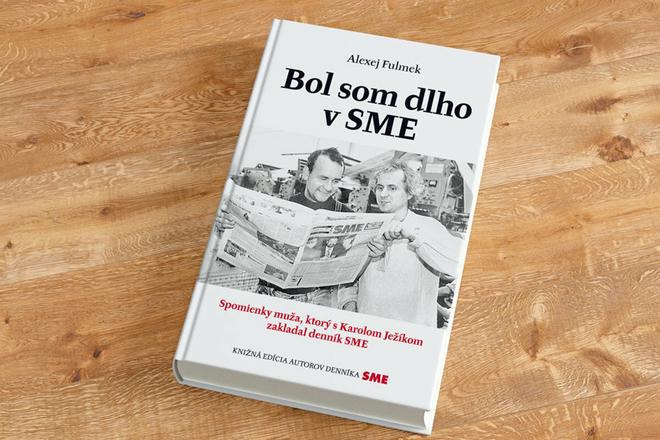

Alexej Fulmek is the CEO of the Petit Press publishing house. In 1993, he co-founded the Sme daily along with its first editor-in-chief, Karol Ježík. He has been part of the story of the daily, and the history of Slovakia, ever since. This extract is from his memoir One Flew Over the Newsprint published in the Slovak original in December 2018.

The idea came from my colleague Pavol Juračka, whose fate later took another twist that landed him in the secret service. He did not work for the newspaper when he became involved with the intelligence service. Secret services have always been interested in journalists and Slovak laws only reacted to this problem much later.

Juračka was a great reporter capable of capturing the story and drama of a situation. He used the methods of the German reporter Gunter Wallraff, who used to infiltrate specific environments and then write his stories from the perspective of a direct participant. In one of his stories, Juračka pretended to be a German businessman interested in buying uranium, Then we got a tip that there was a trade with radioactive material going on, along with proof – a small piece of metal with radioactive uranium dioxide. In the end, the police took over the whole case.

Let's go to Moscow

It was Juračka who told me: “Alexej, Gorbachev fell, you speak Russian well, let’s go to Moscow.” We went to Karol Ježík, who agreed on the spot. That very evening we stood on the streets of Moscow, ignoring the curfew, looking at the armed vehicles around us. That was when the famous picture of Boris Yeltsin was taken, depicting him as he addresses the crowd from a tank in front of the parliament, and our feature story, A Night on the Barricades.

For the first time in my life, I saw death in the streets. The dead body of a young man was hanging from the back door of an armed vehicle. It was the kind of vehicle I learned to drive during my compulsory military service. The man’s head was hitting the road. Pavol broke his ankle as he ran from a blasting cannon, and the defenders of the parliament wrote on a cigarette box for us that we were heroes who spent two nights with the defenders of the Russian parliament.

After the victory of Yeltsin and democracy, we wrote a story called Iron Felix Hung, about the destruction of the statue of Felix Dzerzinsky, the founder of the Russian secret service that preceded the KGB. Totalitarian totems were brought down, and we noticed a small detail: that the bronze statue was dismantled by a German crane of the Krupp company. We even received air time on TV news, and we wrapped up our journey with a feature story about the funeral of the coup victims.

War deprives people of rationality

Later, I directly witnessed the war in Georgia and in Moldova. To become a war reporter, one only needs a few things: to know the context of the war, to be able to get to the front, which is not always easy, to get to the politicians and to reconstruct the events that one witnesses there, in a logical sequence. And, obviously, to survive.

I was often exposed to dangerous situations in which I feared for my life, but I learned to control my fear to prevent it from paralysing me. I witnessed the suffering of people hit by the war, and that is why I am certain that it is one of the sacred duties of journalism to point to the dangers of nationalism.

Nationalism triggers wars, it is the tool of irresponsible, power-thirsty, immature politicians, it is the cause of suffering of ordinary and extraordinary people. It produces tens of thousands of refugees and thousands of dead.

Amid the murdering, I understood that in war conflicts you cannot always identify who is telling the truth and who is right, because the suffering hits one’s emotions so much that one is no longer capable to adopt rational attitudes. One is deprived of any rationality whatsoever, by the reality that one experiences on the front. In my view, this is a very dangerous psychological phenomenon of wars, which leads to some kind of social paralysis, to the loss of civilisation and to the unimaginable violence humans perpetrate on each other.

After the wars, mafia clans arise and draft their members from former soldiers who have learned to kill in the war. Nothing can replace that adrenalin for them, that exciting feeling of being able to take someone’s life and go unpunished. Nothing can replace the strong bond and the friendship between those who fight together.

There are no winners

I brought shrapnel from grenades, landmines, and bombs back home with me. Not like souvenirs, but as artefacts of the destruction brought on by war, a reminder of the experiences I have been through. I remember how I used to tell my wife not to worry about me, that it was a normal job and that I would be careful. And then, face-to-face with the war, as I was huddled in the backseat of a car crossing the frontline and driving down a road destroyed by grenades, I discovered the fundamental human fear inside of me, the fear for one’s own life, which could not care less about the professional duties of a war correspondent.

I tried to tell all this as truthfully as I could in my stories from the frontlines. I’m not sure if I always managed to do that, but the message I brought home with me was clear: the value of peace means more than anything else. In war conflicts, there are no winners on the field. Everyone loses, except those who profit from the war. And you can trust me that this is the main point.

The Slovak Spectator will publish more extracts from Fulmek's memoir in the coming weeks.

(source: Sme)

(source: Sme)