As a small child I used to go with my parents and older brother to the Šúr Nature Reserve near the village of Svätý Jur close to Bratislava. At that time in the 1970s it was a mystical land for me, where my brother and I went on exploratory trips to the concrete pools of the former open-air pool in the spring full of tadpoles. Or I imagined how the carousel, from which only a rusty structure remained, once worked. In the grass under ancient oaks we were finding the mandibles of the European stag beetle, which resembled deer antlers. When I returned here sometime in the first decade of the 21st century, I hardly recognised the place. Around the originally solitary oaks, a new, dense forest had grown. I could see them in their full bucolic beauty only in the winter, when the fallen leaves made their monumental silhouettes visible.

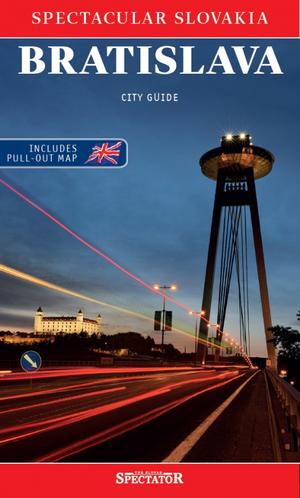

Lost in Bratislava? Impossible with this City Guide! (source: Spectacular Slovakia)

Lost in Bratislava? Impossible with this City Guide! (source: Spectacular Slovakia)

Today, it is possible to admire them again all year round. Nature conservationists, in cooperation with the local self-government, freed the oaks from the young forest and returned cattle grazing to the location. The restoration of the silvopasture has already borne its first fruit - experts have already observed the occurrence of several interesting species of insects and birds.

“Many people do not even know what a treasure Šúr is from a European point of view,” said Peter Lipovský from the non-profit organisation Regional Association for Nature Conservation and Sustainable Development (BROZ). “It is a rare combination of wetlands and forest-steppes characterised by extensive biodiversity. It includes Panónsky Háj, Pannonian Grove in English, an open forest consisting of solitary oaks. In the past, such a silvopasture was common in our country, but today we have it almost nowhere else in such a large area.”

The allure of Panónsky Háj

Šúr Nature Reserve

-Consists of the wetland Šúrsky forest and the forest-steppe Panónsky Háj grove

-Šúr is the largest wet moorland alder forest in Slovakia and one of the last original forests of this type in central Europe. The area of the national nature reserve is 991 ha.

-More than 300 important species of animals, 202 species of birds, 300 species of darning needles, 707 species of butterflies, 85 species of bees, 33 species of ants, more than 120 species of rare plants and other organisms live here.

-Panónsky Háj represents a complex of rare remnants of lowland open thermophilic oak-elm forest. It was the result of long-term human activity in the country, when a xerophilic grove with solitary common oaks, occasionally Austrian oaks, without dense undergrowth was grown here due to grazing.

-One section is a salt marsh with the occurrence of endangered plant species

-The Klenoty Šúra educational trail leads through the reserve. It is 4.1 km long and has six stops. It was built in 2006.

The strip of the unique open oak-elm forest lines a wetland alder forest, which is the core of the Šúr nature reserve. It once served as a pasture for cattle, as the inhospitable gravelly soil on which it grows was never nutritious enough to grow grain or other crops. The cattle grazing ensured that the solitary oaks were not overgrown with young trees.

Nature adapted to grazing and the result of this symbiosis of man and nature was a rare habitat with an unusually rich and varied composition of animals, especially insects and birds. The rarest of them are, for example, the largest European beetle, the stag beetle and the great Capricorn beetle or the European roller and the Eurasian hoopoe.

After unsuccessful attempts to dry Šúr and turn it into agricultural land, the consequences of which it is suffering from to this day, Šúr was declared a nature reserve in 1952. They then expelled the cows from the area as it was not appropriate to graze cattle in the reserve. However, this meant such a change for Šúr that it almost turned fatal.

“This effort for greater protection almost destroyed the object of protection itself, because when grazing stopped in the 1950s, Panónsky Háj started to be overgrown by young trees and began to decay,” said Lipovský.

Oak, as a light-loving tree, suffers from a lack of light in a dense forest and therefore has a shorter lifespan. Really old oaks grow solitary. Therefore, the young trees, which grew after the banning of grazing, almost killed the oaks.

“These oaks were growing as solitary trees for 150 or 200 years,” explained Matej Čičo, forester and director of 1. Svätojurská, a municipal company administering the forest of Svätý Jur. “They did not need to stretch up for the light and therefore had wide, spreading crowns. When they began to be overgrown with young trees, mainly maples, they could not compete with them. If it remained that way for another 20-30 years, they might have been completely suffocated.”

Cows are again taking care of Panónsky Háj. (source: Jana Liptáková)

Cows are again taking care of Panónsky Háj. (source: Jana Liptáková)