One year ago, we discussed the regional economic gaps between Bratislava, western and eastern Slovakia. This may have seemed as if Bratislava was the land flowing with milk and honey, but this is certainly not the case.

Today, we will look at what ails Bratislava and we will find one important issue where Bratislava significantly underperforms the rest of Slovakia.

Not in my back yard

The big issue, and one frequently discussed in the media, is the lack of housing in Bratislava proper. Bratislava has 436 apartments per 1,000 inhabitants, less than Prague, Warsaw, Budapest, and Vienna, and less than the EU average. And the trend is not favorable either: in 2020, Bratislava finished building 2,793 residences, which is less than the surrounding districts of Malacky, Pezinok and Senec combined (2,983), while Bratislava has roughly double the population of surrounding districts. When we look at started construction, the situation is even worse: the district of Senec (pop. 95 ths.) alone started building more dwellings in 2020, than the whole city of Bratislava (pop. 440 ths.). Bratislava has too few flats, and is building too few flats, further deepening the gap in housing.

The problem is, quite simply, that it is very difficult to start building in Bratislava. The developers have their own stories, but even when the city itself proposed to build rental apartments in Prievoz this year, it failed because of opposition from residents. Bratislava is experiencing what has become know as Nimbyism (from NIMBY=Not In My Back Yard), where residents oppose basically all development in their vicinity.

This, of course, explains why flats in Bratislava are so expensive and the prices keep on rising: when supply is limited, prices have to rise. And as long as supply is limited, prices will keep on rising, and people will continue to look for housing opportunities outside Bratislava, for example in Senec, putting more pressure on transportation. And herein lies the second issue.

The taxes are too damn low

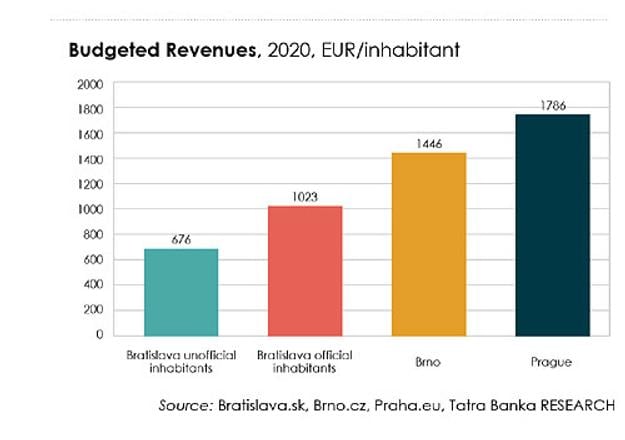

The second problem of Bratislava is that its budget is too low (a problem shared with basically all municipalities of Slovakia). When we compare Bratislava’s budget with Prague, Bratislava had budgeted revenues of €1,023 per inhabitant in 2020, while in Prague it was €1,786 per inhabitant, or roughly 75 percent more. Even in Brno, a non-capital city, without an underground metro but with trams, the budgeted revenues stood at €1,446 per inhabitant, more than 40 percent more than Bratislava.

With revenues so low, it is difficult for Bratislava to build new housing and alleviate the issue, even if it were able to overcome the opposition of Nimbys. Furthermore, it is also difficult to build and maintain a public transport infrastructure to foster suburbanisation. For comparison, Bratislava’s tram network has a total length of 41.5 km, while Brno’s stands at 70 km, and Košice’s, with roughly half of Bratislava’s population, stands at 34 km.

The opposite of Dead Souls

In the novel Dead Souls, Nikolai Gogol describes them as long dead serfs, who were, however, still formally registered and landowners were paying taxes for them. Bratislava has the exact opposite problem: the citizens are alive and well, but there are in fact more people actually living in Bratislava, than are formally registered, and, to make the opposite to the novel even more poignant, Bratislava is not receiving tax revenue for them.

This exacerbates the issues above. According to cell phone location data, the real number of people living in Bratislava is not the official number of 440,000, but instead 666,000. If that is the case, the number of flats per 1,000 inhabitants is not the above mentioned 436, but 288. The revenue per inhabitant drops to €676, less then half of Brno’s and about a third of Prague’s.

Is there a problem?

Of course, the question is, what are the downsides to this? If there is not enough housing, won’t prices rise until they find an equilibrium? If trams are not built, will people not use cars? Of course, these outcomes are perfectly possible, but just as taxes create deadweight loss, so does limiting the supply (and a low housing stock is limiting the supply).

Consider Tokyo, where new construction proceeds in line with population change, and flat prices change at the same pace as consumer price inflation. Or Berlin, which became a vibrant city and a hipster mecca precisely because of cheap housing. Or San Francisco, California, the unofficial capital of Nimbyism, where a lack of new housing priced out middle class residents and caused a homelessness epidemic.

The bottom line is that the lack of housing and finances is limiting Bratislava’s growth both in terms of people and quality of life. While defending and maintaining the status quo is a reasonable political goal, the current limits do not satisfy this goal: with low housing and money, housing will become ever so expensive, and infrastructure will continue to deteriorate.

Tibor Lörincz is economic analyst of Tatra Banka

Originally published in Connection, the magazine published by AmCham Slovakia

Author: Tibor Lörincz