Ukrainian version | Slovak version

It was a Thursday, and Oleksandra Potrohosh was standing on a pavement outside the Russian embassy in Bratislava. She was barefoot and half-naked, her body and underwear were covered in blood-red paint and her mouth was taped shut.

In her left hand, she held a blue-yellow sign that read: “Rape is a war crime.”

More than three months into the war in Ukraine, on June 2, 2022, she and several other female activists, including former journalist Alexandra Demetrianová, protested against the sexual violence being commmitted by Russian soldiers in Ukraine, while most people in Bratislava went about their everyday lives. On the radio that day, they may have heard news about Slovakia sending howitzers to Ukraine and the EU adopting a new package of anti-Russian sanctions.

The protest was far from Potrohosh’s only response to the war.

The Ukrainian artist, who in the world of art goes by Kasha thanks to a friend who invented the name by accident, created the “Berehynia” artwork. It was one of her very first pieces of art that reacted to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The goddess Berehynia is considered a symbol of good and positive forces of nature in Ukraine, but Potrohosh decided to reimagine the symbol in her video installation. Naked, she paints her body, which represents Berehynia for this purpose, using blood-red paint in front of a camera.

“I stain the symbol with blood, an attribute of war,” the artist explains in a post on Instagram. “At the same time, I put [two figures] in opposition: a male representing war, and a female representing a victim.”

Earlier this year, Potrohosh created an artistic performance, “Body Scars”, to remind people that Ukrainian people, often women, continue to be raped by Russian soldiers. After a while, Potrohosh takes her clothes off, revealing signs like “loot” and a “sex slave” painted all over her body. The performance, which resembles a ritual, recounts the story of a woman who has her own place in society but who turns into a number after being raped.

“The most powerful artworks of mine are those that I created during the war,” she tells The Slovak Spectator.

Inspiring uncle

Potrohosh, an ethnic Slovak who holds Ukrainian citizenship, was born in the western Ukrainian city of Uzhhorod. She is a Rusyn, a member of the Eastern Slavic ethnic group who live in the cross-border area of Ukraine, Poland and Slovakia. Known to Slovaks as Subcarpathian Rus, this region was once part of interwar Czechoslovakia, the Kingdom of Hungary and the Soviet Union, none of which now exist, before it became part of modern-day Ukraine.

“I have a lot of mixed roots,” she says.

There are Ukrainians, Slovaks and Hungarians in her family. For example, one of her grandfathers was a Hungarian Slovak from Prešov, eastern Slovakia, who moved to Subcarpathian Rus in the interwar period and remained there.

Potrohosh was born into a family of physicists. Despite studying mathematics in secondary school, she has always been attracted to art. Her uncle, a blacksmith, was a huge inspiration to her.

“I admired him,” the artist told the fjúžn magazine, “He was such a beautiful authority for me and also proof that you can make money with art.”

It took time for her parents to get used to the fact that their daughter wanted to earn a living as an artist. But even today, she does not share all her art with them.

“It’s better that way. They’re still conservative when it comes to creativity,” Potrohosh explains.

She was 18 when she came to Slovakia to pursue studies at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design (VŠVU) in Bratislava. It was her first trip abroad, but she was used to hearing Slovak. She grew up watching popular Slovak children’s television programmes such as “Elá Hop!” and “Večerníček”, as well as the Slovak-language version of the Japanese animated series Pokémon.

Accepting her own self

Still, she had to overcome several fears in Slovakia.

The artist initially struggled to reveal to people where she came from. She thought that people would not like her being Ukrainian.

“Therefore, I used to tell people that I was from ‘the east’” she says.

The more she was asked such questions, the more tired she grew of such evasive answers. Today, she admits that the reason for dismissing those questions was the search for her own identity as well.

Potrohosh says that she has always felt like a ‘white crow’, which is a Ukrainian term for an odd person that stands out in the crowd. It took the artist some time to accept who she was and to embrace the often ‘demonised’ Ukrainian phrase. Today, she even says that being the ‘white crow’ gives her more freedom.

Her school and the war, but also situations at the Foreigners’ Police office in Bratislava, where she was reminded many times that Slovak was the official language in Slovakia, or by a cab driver who told her that Ukraine would lose the war, ‘helped’ her to start realising and embracing her roots more.

“Now, I can present myself as a Ukrainian artist,” she says, “Before, I felt that I should suppress my identity.”

At VŠVU, the Ukrainian had to work harder than her classmates. She had no formal art education, despite taking some art lessons as a child and trying to study pottery at the Transcarpathian Art Institute. After one year at the institute, she decided to move to Slovakia. In addition to studying art history and theory, she was also worried about her drawing skills. She often doubted herself. It was an intermedia course that she took in the Slovak capital that gave her a boost and showed her that there were many other ways to create art. Her concerns vanished.

“Without university, I would not have been formed in the way I am now,” she thinks.

Thanks to her university experience, the Ukrainian artist says, she could explore liberal views and accept herself and her art.

Why Potrohosh gets naked

Potrohosh characterises her art as chaotic.

In recent years, she has authored nearly 30 art projects, ranging from paintings, collages and masks to video installations and performances.

“I’m not interested in the art form, I’m interested in the topic I want to discuss,” she notes.

Feminism, self-harm, death, violence, climate change, and even the war are among the topics that she has touched upon. Currently, she is exploring microbiology and fungi in her art.

Sometimes, she gets naked to highlight how close these topics are to people who may not realise it. It was in this way, for instance, that she portrayed the impact of humans on the environment in her “Mother Nature” project, or explored the topic of Instagram, the naked body and filters in her “emoG” project.

“I’ve seen people leave during my performances because they could not handle a given topic. They experienced it so strongly through me,” Potrohosh says. “I took it as a compliment.”

Those who stay until the end of her performances sometimes decide to hug the artist to thank her.

What Potrohosh likes about art, she says, is the opportunity for her to respond to various serious topics and explore the world, but she also believes that art helps her to understand herself better – and gives people the opportunity to understand her.

‘Nostalgic Experience’

Although she has been dealing with far-reaching topics in her art, the 28-year-old artist no longer yearns to save the world. She says that she feels satisfied with the impact on her own community in Slovakia.

“That suits me better,” the artist says.

Moreover, she appreciates that her circle of friends does not judge her for the way she approaches art and depicts the world. In Uzhhorod, she says, people are more conservative than in Slovakia and could not bear the rush of explicitness in her art.

“Even the way I dress attracts many more glances in Uzhhorod than here,” Potrohosh says.

Nevertheless, she admits that the openness she feels in Slovakia may be the result of living in a bubble that she has built around herself. She fears that it would be a different – conservative, Catholic and homophobic – experience if she lived in a Slovak village. Still, it is her desire to move to the countryside.

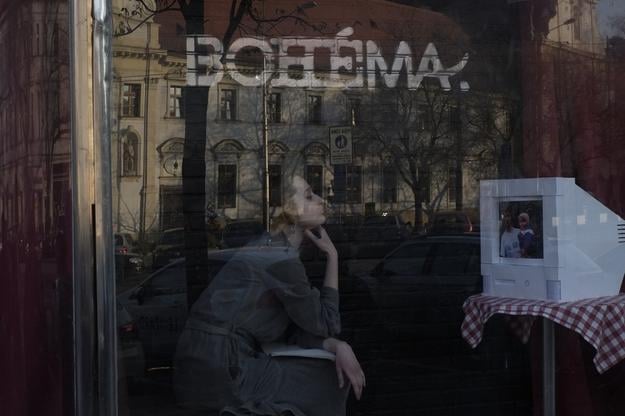

Potrohosh captured this difference of opinions in an older performance of hers entitled “Nostalgic Experience”. The inspiration came from her family. She sits in a pub window, looking at an old photo of her father and herself. As she sits there, she reflects on the relationship between her father, with his more conservative views, and herself and her own views, which are at odds with her father’s.

“His views had a depressing effect on me,” she writes in the description of the performance. “But over time, I learned to systematically separate ‘dogmas’ and to purposefully act contrary to them.”.

Potrohosh believes that what people need in order to understand others better is “the courage to change their opinions”.

This story was published with support from the International Press Institute's Ukraine regional reporting fund.

On Thursday, June 2, 2022, a symbolic protest took place in front of the Russian embassy in Bratislava. (source: bencssik)

On Thursday, June 2, 2022, a symbolic protest took place in front of the Russian embassy in Bratislava. (source: bencssik)

Kasha Potrohosh presents the Berehynia project at the cultural centre Tabačka Kulturfabrik in June 2022. (source: Facebook/Tabačka Kulturfabrik )

Kasha Potrohosh presents the Berehynia project at the cultural centre Tabačka Kulturfabrik in June 2022. (source: Facebook/Tabačka Kulturfabrik )

The Body Scars performance by Kasha Potrohosh. (source: jedinadora)

The Body Scars performance by Kasha Potrohosh. (source: jedinadora)

Some of the masks created by Kasha Potrohosh. (source: František Mihalék)

Some of the masks created by Kasha Potrohosh. (source: František Mihalék)

Kasha Potrohosh in an older performance of hers entitled “Nostalgic Experience”. (source: Courtesy of K. P.)

Kasha Potrohosh in an older performance of hers entitled “Nostalgic Experience”. (source: Courtesy of K. P.)