You can read this exclusive content thanks to the FALATH & PARTNERS law firm, which assists American people with Slovak roots in obtaining Slovak citizenship and reconnecting them with the land of their ancestors.

The Holocaust was an extreme tragedy that caused immense suffering; among the families affected is that of American Gregory Stein. His ancestors emigrated from what is now Slovakia at the start of the 20th century. After the Second World War, all contact with family and relatives in Europe was lost and it was assumed that they had perished in the Holocaust, and with them the connection to this part of the world, besides an old postcard and a Hebrew Bible.

As is a recurring theme in these series, things changed during the pandemic.

Although Stein himself had been interested in genealogy for quite some time already, his search brought him only limited information. Then in early 2020, he got a call from a man in San Francisco that set him on a path to discover not only several dozen living relatives scattered across the world, but to trace his family origin back to early 19th century, to the territory of present-day Slovakia.

Next to no connection

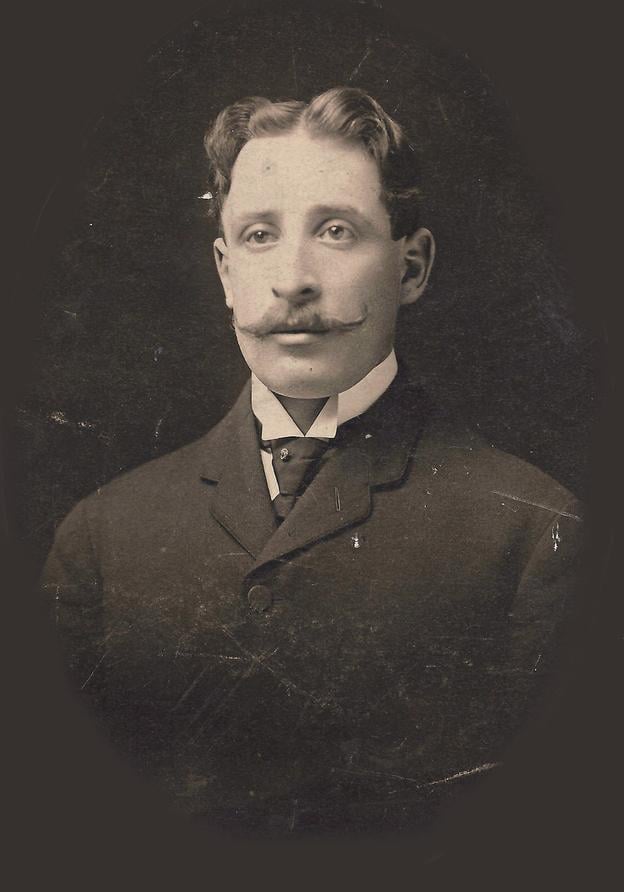

Even before he learned about his family history, Stein knew that his great-grandfather, Nathan Stein, was from a family of eight kids. Together with his younger brother, he emigrated to the US in 1902 when they were in their early 20s. They didn’t know the language, and had just a handful of dollars in their pocket.

They settled in Hubbard, Ohio, and worked as butchers, probably something they had picked up back home. Both got married and raised their kids there, but never returned to their homeland. Stein got to meet his step-great-grandmother, but not his great-grandfather nor his great-grandmother, who both died before he was born.

What was perplexing to Gregory Stein was that despite them being from the territory of present-day Slovakia, they spoke Hungarian. That can be explained by Magyarisation, an assimilation process of non-Hungarian inhabitants of the Kingdom of Hungary that saw them adopting the national identity and language.

His grandfather continued to work in the food industry – he was a coffee salesman and later started a business making frozen foods for restaurants, hospitals, and schools. It grew to the point where he was able to sell it in 1980 to Oscar Mayer, a large, national corporation.

Like many others, Stein tried using Ancestry.com to learn more about his family. The resources were, however, limited at the beginning. He found his great-grandfather’s naturalisation papers, ship manifests and similar documents. Also, there was a postcard that Nathan Stein passed down to his son and so on until it got to Gregory Stein. In it, there are several people, probably in their 50s, and several names are written on the back. There was no date, but it looks like it was taken in the 1930s.

Aside from an old Bible, it was the only connection with Europe he had.

"There was no family, they had lost touch with everybody. As far as we knew, everybody had been killed in the Holocaust and that was it. That was kind of the end of the story," Stein said.

Scattered around the world

In early 2020, Stein got a call from a man named John Temple, a professor of journalism living in San Francisco, who turned out to be his third cousin once removed. That set him on a path of discovery of almost 40 family members from various places around the world that had ended up scattered around the globe due to the Holocaust.

During WWII, Temple’s mother was living in a basement with others, including a French doctor. The house had been taken over by the Nazis to serve as their headquarters. Since they were in need of medical help, they wanted the doctor to help them. He agreed on the condition they would not kill the Jews and thus saved their lives. After the war, his mother emigrated to Canada. Interestingly, Temple was able to find the family of the French doctor.

However, Temple's mother had a brother but didn’t know what had happened to him. When John visited Yad Vashem, a memorial to the Jews killed in the Holocaust as well as people who helped them, located in Jerusalem, he left a record of his uncle there.

This record was picked up by a genealogist in Budapest, a dear friend of a distant cousin of both Gregory and John who had been doing her own research into the family history at the time. She then contacted John. They then hired the genealogist who started digging into everything.

"She spoke enough Slovak that she could figure out what happened. Long story short, over the next couple years, she figured out all these relatives we had and people that had emigrated," Stein said, adding that after the war, some moved to places such as Canada, Australia, and Israel. There were even other relatives in Budapest who had no idea they were descended from Jews from Slovakia. Even after the war was over, antisemitism was still rampant and those who survived found their homes occupied by people who didn’t want to give them up. With nothing to hold them, they left.

The mother of the relatives that now live in Haifa, Israel, had survived for a couple of years during WWII by hiding and living in the woods in Slovakia as a small child. They knew they had some connection to Slovakia, but nothing beyond their mother’s connection. This digging helped them fill in the blanks as well.

Closing the loop

"We kept digging and digging and really found tons of information and connected all these people. Then in the summer of 2022, there were 38 of us and we got together in Budapest for a sort of a family reunion," Gregory Stein recollects, adding that they figured out they were Slovak and descendants from a Stein lineage that goes back to the early 1800s. Stein's great-great-great-grandfather was Izsák Stein, who was born in 1807 in the village of Hanfalu (now Huncovce) in the historic Spiš region in northern Slovakia, and his great-great-great-grandmother was Hani Friedländer, born in Liptovský Mikuláš in 1809. Both are buried in Liptovský Mikuláš in the cemetery that was converted to a park in 1991. Other ancestors were innkeepers, merchants, businessmen and lived in communities below the High Tatras.

Sadly, they also discovered that many family members perished in the Holocaust. They were either shipped out to the concentration camps or just ended up in the ghettos. The genealogist was able to identify several distant family members and their last places of residence. There is a project called Stolperstein, the goal of which is to commemorate Holocaust victims. A Stolperstein is a small brick bearing a brass plate with a name on it. They had five of them made for lost family members and were able to install them in Budapest.

Among the 38 relatives who met was Anna, an elderly woman now in her early 90s, who was a young girl during the war. She remembers living in a ghetto and seeing people getting shot. According to Stein, she had not talked about it before. This gathering allowed her to close the chapter.

They hired a bus to get them to Poprad near the High Tatras to visit the whole area. Unfortunately for Stein himself, he got Covid and became symptomatic on the way and had to return home. However, he returned the following year to see everything.

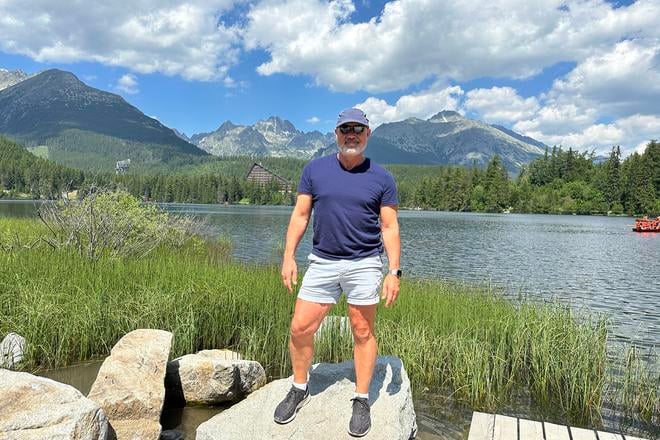

"It was the trip of a lifetime. I went back, rented a car, drove up and spent several days up there, saw all the little towns, the old Jewish cemetery, and the old synagogue that is now a tourist destination. I fell in love with the place. It's so beautiful and I learned a lot about my history, walked the streets and went to the graveyard where my great-great-grandparents were buried. It was really pretty special to be able to sort of close the loop," he recalls.

The only thing that dissapointed Stein was that he couldn't find anybody that was related to him in Slovakia.

"I guess it's reassuring, though, that sentiment has changed, young people have a much different perspective. There's much more tolerance for other perspectives and other people. I never felt any antisemitism," he says.

To remember

When the Slovak parliament passed the law that allowed descendands of Slovak emmigrants to become Slovak citizens in 2022, Stein seized the opportunity.

"I thought it was cool. I've got kids and I'm set up here. It’s not like I'm going to move to Slovakia. It just gives me another touch point to connect to my Slovak history," he explains, adding that he already has the Slovak living abroad certificate and the residency permit that potentially allows him to come and live and work in Slovakia.

He also submitted the application to get Slovak citizenship. Since his children are young and below 14 years of age, he was able to include them on the citizenship application as well.

"For them it's much more meaningful because they will then become EU citizens. Particularly in this day and age where the world is changing geopolitically, having options is a good thing. Their mother is Canadian, so there's that as well," he says, adding that both kids are enrolled in a French school and are fluent in French and Spanish.

"I'm making sure that my kids really understand where they come from. When they’re old enough, we'll go to Slovakia to visit all those sites and I'll tell them all the stories," he says.

"I joke that the only reason I'm doing it is so I have something to talk about at parties," he concludes, adding that he may have a hard time deciding who to cheer for in the upcoming ice-hockey world championship should both countries meet.

Spectacular Slovakia travel guides

A helping hand in the heart of Europe thanks to our Slovakia travel guide with more than 1,000 photos and hundred of tourist spots.

Our detailed travel guide to the Tatras introduces you to the whole region around the Tatra mountains, including attractions on the Polish side.

Lost in Bratislava? Impossible with our City Guide!

See some selected travel articles, podcasts, and traveller info as well as other guides dedicated to Nitra, Trenčín Region, Trnava Region and Žilina Region.

Gregory Stein at the Štrbské Pleso resort in the High Tatras. (source: Archive of G. S.)

Gregory Stein at the Štrbské Pleso resort in the High Tatras. (source: Archive of G. S.)

Nathan Stein. (source: Archive of G. S.)

Nathan Stein. (source: Archive of G. S.)

An old postcard of Nathan Stein with siblings. (source: Archive of G. S.)

An old postcard of Nathan Stein with siblings. (source: Archive of G. S.)

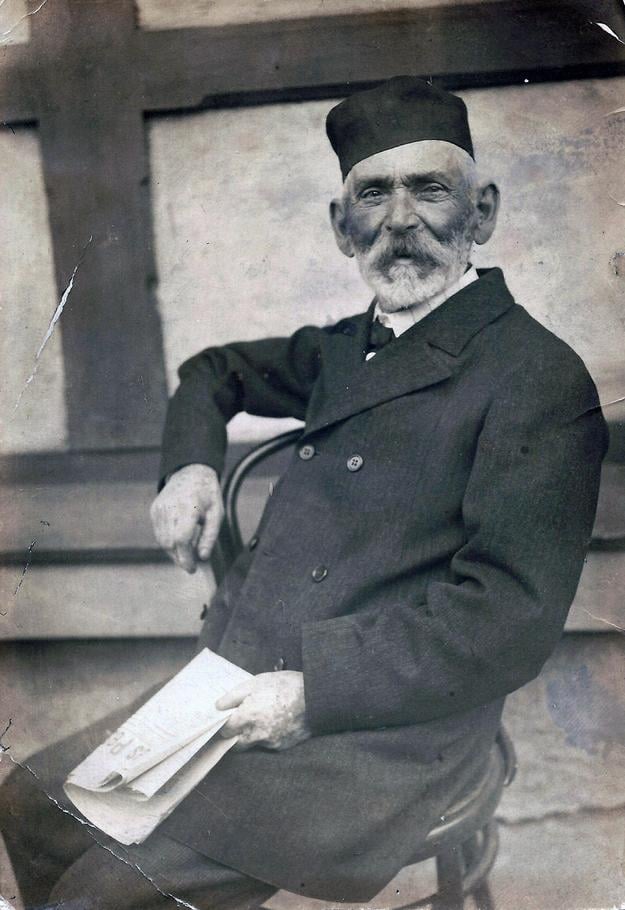

Gregory Stein's great-great grandfather, Moritz Stein, who was born in the village of Liptovský Ondrej near the town of Liptovský Mikuláš around 1840. He was an inn keeper. He and his wife are buried in Poprad. (source: Archive of G. S.)

Gregory Stein's great-great grandfather, Moritz Stein, who was born in the village of Liptovský Ondrej near the town of Liptovský Mikuláš around 1840. He was an inn keeper. He and his wife are buried in Poprad. (source: Archive of G. S.)

The grave of Moritz Stein. (source: Archive of G. S.)

The grave of Moritz Stein. (source: Archive of G. S.)

Gregory Stein at the Jewish graveyard in Huncovce. (source: Archive of G. S.)

Gregory Stein at the Jewish graveyard in Huncovce. (source: Archive of G. S.)

The Liptovská Mara water dam near Liptovský Mikuláš is dubbed the Liptov sea. (source: TASR)

The Liptovská Mara water dam near Liptovský Mikuláš is dubbed the Liptov sea. (source: TASR)