A glossary of words is also published online.

Despite their ancestors being forced to move overseas for socioeconomic and political reasons in the past two centuries, often losing touch with their homeland, Slovak Americans have set out to reconnect with Slovakia.

“It is important for me to know where my roots are, where I come from, who I am, and why I am the way I am,” Cynthia Sandor, a 60-year-old American and native of Florida of Slovak-Austrian descent, said.

Communists took our rental car apart. They took the doors off, a large mirror with wheels rolled under the vehicle, and they searched all the luggage.“

A new chapter for a part of her family began in 1921 when her grandfather Mihaly, born in present-day central Slovakia, arrived at Ellis Island aboard the SS Hudson and settled in Connecticut, where his brother Jan had lived.

Slovaks started to embark for America on a mass scale as soon as the American Civil War ended in 1865 due to the lack of opportunities and poverty in the Hungarian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which dissolved after WWI. Though they worked hard in the mines, steel mills and on the railroads in the Midwest and Northeast, most of them decided to not return home. As many as 619,866 Slovaks resided in the USA in 1920, according to the US census, mostly in Pennsylvania, Ohio, New Jersey, New York, Illinois and Connecticut.

Nearly a hundred years later, in 2010, about 750,000 Americans were estimated to have a Slovak background. Yet, just a small number of these Americans, most of whom are older in age, are eager to explore their ancestry, researching historical records online and touring Slovakia with the help of locals.

“Prior to the fall of communism, many did not have the courage and did not know what to expect,” tour guide and amateur genealogist Viera Marecová claimed, adding that some Americans are afraid of not being adopted by their Slovak family even today.

“My blood runs through you.”

Communists were still in power in the early eighties when Sandor, then in her twenties, and her parents visited their Slovak family for a few days. They had to wait for two hours at the border because they were Americans who had flown into Germany and had driven through Austria before reaching Czechoslovakia.

“Communists took our rental car apart. They took the doors off, a large mirror with wheels rolled under the vehicle, and they searched all the luggage,” Sandor remembered. “I remember watching the German Shepherd sniff through our belongings. We just sat in a little coffee shop helpless until the complete search of the vehicle was completed.”

But it was the moments spent with her Slovak family in Bratislava and on a farm near Zvolen that Sandor has kept close to her heart, including meals at her great-aunt Mary’s home. Sandor said Mary made a gesture upon their departure from the farm that gave her chills.

“She was dressed in black, took my arm, and started rubbing it with her hand,” Sandor recalled. “My great-aunt Mary said: ‘My blood runs through you.’”

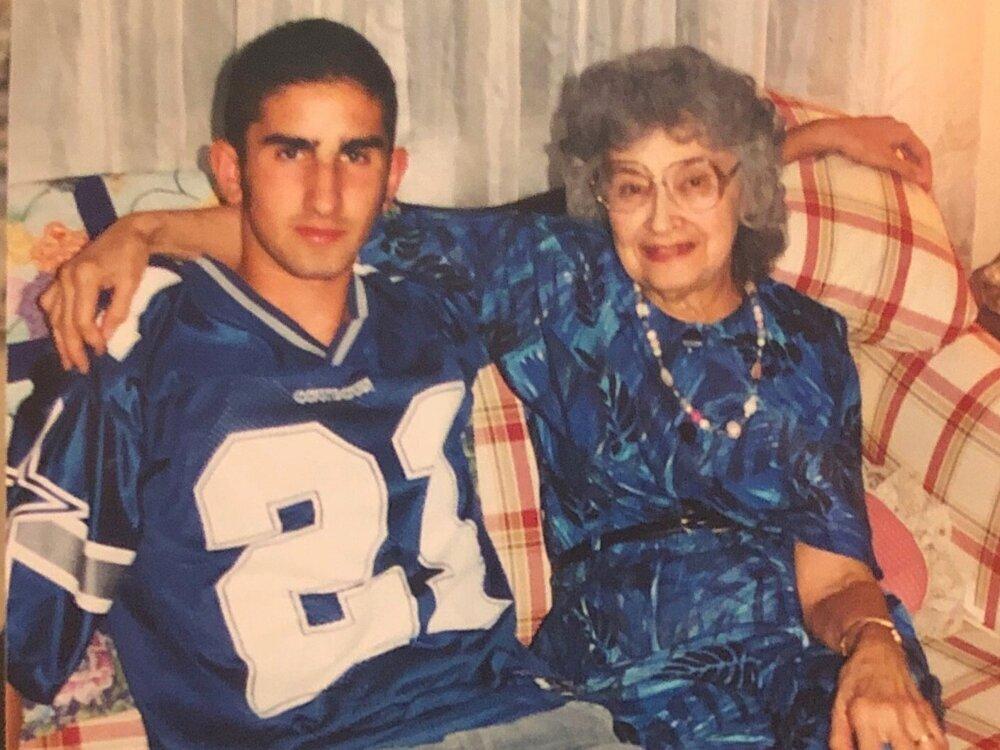

When Sandor’s father Robert, who somehow contacted their Slovak family in the eighties, died in 1991, she lost contact with them. Only old photos, in addition to memories, remain.

Sandor has not, however, given up on the idea of finding her Slovak cousins Peter and Jozef, whom she believes are still residing in Bratislava. Unlike her siblings who are not interested in their ancestry, Sandor keeps working on her family tree. In 2022, she plans on visiting Austria, Slovakia, and Poland in the hope of learning more and reconnecting with her family.

Emigrating easterners

Thanks to guides and genealogists, many Slovak Americans have managed to visit the places of their ancestors, in particular the east of Slovakia, over the years.

Being on the ground and looking for houses, relatives, and graves rather than flipping through historical records, Marecová from the Spiš region has, for example, assisted a number of Americans of Slovak-Jewish descent.

Several years ago, she helped an old Dallas man who had sought the courage to return to Slovakia all of his life. He grew up in an orthodox Jewish household in Ladomirová, by the Polish border, and moved overseas as a youngster after an argument with his father back in the thirties. Before WWII, he had urged his big family to move to America, but they declined. None of them returned home after the war.

“As soon as we came to the village, I stopped an old lady and asked if she knew the man’s family, to which she nodded,” Marecová said. “She looked at him and cried out: ‘Is that you, Jožko?’”

It turned out they were childhood friends.

Most of those who left for America had lived in eastern Slovakia, in the former counties of Uh, Šariš, Abov, Spiš, and Zemplín. The Uh county was hit hardest by emigration in the whole of Hungary, Milan Belej from the Nitra State Archives said.

Cherry on the cake

While many Slovak Americans succeeded in reconnecting with Slovakia and their families, Parviz Malakouti-Fitzgerald, an American of European-Iranian heritage, has not reached out yet.

He has known for years that he had Slovak ancestry, growing up with his mother Rita and Ohio-born grandmother Elizabeth, whose maiden name was Kolenich and was half Slovak, but his interest has become more intense in recent years as he found a larger Slovak diaspora community online.

As people older than you start to die, you feel like you are losing a connection to your past, and it suddenly became important to find out where I was from.“

A few months ago, he learned that Slovak writer Ivan Kolenič was born in Zvolen, which is the area where his great-grandfather came from. He is busy with advocacy at the moment, but he wants to put some more serious effort into finding his family’s distant relatives later this year.

“I have a big fantasy of making contact, taking my mother to the small town or towns where they are and meeting them all,” he said.

Meeting relatives is “a cherry on the cake”, genealogists approached by The Slovak Spectator agreed, but it is the toughest thing about the family search, and it cannot be taken for granted.

“Even if you find someone with the same last name in the village where the ancestors of a client came from, they are mostly older people who are worried about becoming victims of fraud. They are unwilling to speak,” genealogist Marek Rímsky emphasised.

However, most reunions end happily, according to genealogists, despite the language barrier.

Rázus, who has been in the craft for almost 20 years and founded the Slovak Ancestry group on Facebook, helped a few hundred Slovak Americans, including jazz pianist Les Horan, who recounts his story in the book They Forgot to Tell Me I Was Jewish. Through graveside flowers, the Prešov-based genealogist also helped reunite John Selecky, whose ancestors moved overseas as teenagers in the late 1880s, with his family in Bardejov.

“Selecky is the story of a typical migrant. All of his grandparents were Slovaks, miners in Pennsylvania who achieved their American dream,” Rázus recalled the story sparking his interest in genealogy.

The want comes with older age

Today, visits to the Slovak state archives by Americans are on the decline as historical records can be found on the Familysearch and Ancestry websites. Nevertheless, those who contact the institutions are often surprised by discrepancies between what they were told and what the records say.

“Their ancestors left the territory of Slovakia many times as illiterate. When they registered in the USA, various errors occurred in the dates and names of localities,” Peter Brindza of the Trenčín State Archives said.

Also, it matters in which language a name was entered in vital records, Alena Bolfová of the Banská Bystrica State Archives noted. After the establishment of Czechoslovakia in 1918, vital records were kept in Slovak, no longer in Hungarian and German.

To make things easier before her first trip to the village of her great-grandfather, Hrabušice, near Spišská Nová Ves, in 2015, Pennsylvania-born pensioner Linda Stanko decided to ask genealogist Michal Rázus to do some more research.

After her arrival, Erik Ševčík from the Adventoura travel agency, who also helped Andy Warhol’s cousin in the past, showed Stanko around the country. There is always “a lot of excitement, tears and happiness” during genealogical tours in the east of Slovakia, where most Rusyns also come from, he said. Although Stanko has found no living relatives, she developed a nice bond with other Stankos in Hrabušice who have adopted her since.

Explaining why it felt important to reconnect with Slovakia, Stanko said: “As people older than you start to die, you feel like you are losing a connection to your past, and it suddenly became important to find out where I was from.”

Listen to the Spectator College podcast with Linda Stanko:

The Spectator College is a programme designed to support the study and teaching of English in Slovakia, as well as to inspire interest in important public issues among young people.