You can read this exclusive content thanks to the FALATH & PARTNERS law firm, which assists American people with Slovak roots in obtaining Slovak citizenship and reconnecting them with the land of their ancestors.

This is the second of a two-part series on how Slovak emigrants settled in and made new homes in the USA, focusing on their work, social and cultural lives. You can read the first part here.

How much did they earn?

With factories operating non-stop, workers laboured six to seven days a week in 12-hour shifts. Day and night shifts alternated every week, and each worker was entitled to a day off every other Sunday. However, Saturday evenings were a time for entertainment, which often lasted into the night.

By the early 1930s, many American factories already had modern equipment. Housed in large halls that were heated in winter, trucks could safely pass through. Workers protected themselves with gloves and aprons, but only wore light canvas caps on their heads.

In larger cities, many people commuted to work by subway, a novelty for Slovak workers, as was the busy car traffic in American cities. They had to arrive at work at least 10 minutes before the start of the shift so that everyone could man their post on time. No one could leave without being replaced. A bell rang five minutes before lunch so that everyone had time to wash their hands. Some factories had their own canteens, while in others workers had to bring their own lunch from home.

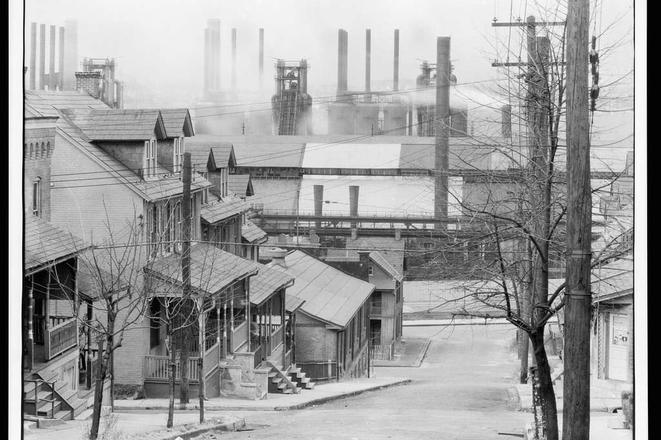

For employers, immigrants were often the last choice when hiring, but the first when laying off. Slovak immigrants worked mostly as unskilled labour in difficult conditions for low wages. Allegedly, they had little opportunity for professional development, despite the experience they had gained over time. However, many sources mention their hard work and willingness to perform physically demanding work. Despite the difficult working conditions, in the 1930s they were still convinced that they would have a worse life in Czechoslovakia.

The wages varied by area and type of work. At the beginning of the 20th century, a miner in Johnstown earned one dollar per ten-hour shift a day, six days a week. The wage was relative to the amount of material extracted, so many worked overtime. The average annual wage of urban workers rose from $1,171 in 1921 to $1,408 in 1928. By 1930, workers in Ohio earned $1,445 on average, in Illinois $1,465, in Michigan $1,555, in Indiana $1,335, and in Wisconsin $1,305. The daily wage was about three to four dollars until the mid-1930s.

The Ford Motor Company was among the best of employers, its workers earning about five dollars a day in the 1920s; by the late 1930s they earned $1.50 an hour. Based on the August 1930 story How Ford Workers Live on $35 a Week, we know that the minimum daily wage was $7 for a five-day workweek. They could earn around $1,800 a year and were entitled to two to three weeks of unpaid leave, or “vacation.”

A time of crisis and unemployment

The Great Depression had a significant impact on the lives of Slovak immigrants. In letters, they wrote about deteriorating conditions in the early 1920s. For example, Štefan Alušic from Racine, Wisconsin, wrote in 1922 how his wage dropped to 17.5 cents an hour, while many companies also reduced working hours. He himself worked only five hours a day. Similarly, Pavol Madigar described in a letter from 1924 how his work was reduced to two days a week, which meant he could not even earn a living.

In 1930s, the crisis forced many Americans to move for work. For foreigners, this often meant returning to their old homeland. Since many still owned property in Slovakia, they believed that they could better support their families by working their own land.

The correspondence of the Benkov family from Ohio, describing mass layoffs and salary cuts in 1933, also gives us an idea of the situation. The correspondence, in which associations and organisations asked for financial assistance for members in need and their families, also gives a picture of the unemployment of Slovaks at the turn of the 1920s and 1930s. The requests were so numerous that the National Slovak Association in Pittsburgh had to introduce a rule that a member could only apply for support once a year.

While employment among American women was increasingly popular, it was not so common for Slovak women in America. They were most often employed in the food and clothing industries, where in 1920 they earned $8 to $17 a week, depending on the state. In the 1920s, when many companies introduced the eight-hour workday, employees were given four extra hours of free time each day without losing their income. This allowed women to manage their household while working and occasionally earn extra money in canneries, where weekly wages reached $18 to $31. Everyone tried to use their free time actively within the community.

Keeping Slovak culture alive

Slovak communities in the US had a rich social life. Organisations regularly held dance parties, balls, New Year's Eve parties, and the like. In the 1930s, banquets were held more frequently; their popularity increased especially with the arrival of the Matica Slovenská delegation at the end of 1935.

Sports activities were an important part of life. The older generation was mainly engaged in gymnastics in the Sokol organizations, while the second generation leaned towards American sports, especially baseball. The Sokol organisations held not only sports events, but also picnics, festivals, public exercises, and trips. "The youth here are crazy about sports. That is their idol," wrote Viktor Blahunka from Chicago.

Education and literature played a key role as well. The second generation of Slovaks showed an intense interest in their roots. Czechoslovak culture, history and literature were taught at American universities, and lectures and film evenings were also held.

They would subscribe to newspapers that brought news both from the US and their old homeland. Dictionaries, spelling books, textbooks, reading books and practical guides about life in America were published as well. Organizations from Slovakia – Matica Slovenská, the Czechoslovak Red Cross, the Czechoslovak Agricultural Museum in Bratislava, or private individuals would also sent literature overseas.

Even Columbia University asked Matica Slovenská for Slovak books. The Cleveland Public Library had amassed an impressive colletion of 450 Slovak books by 1918. In the 1930s, the demand increased for comprehensive books on Slovakia, which would include history, geography and economic conditions. Back in Slovakia, people yearned for historical novels and stories from the lives of Slovak emigrants in the US. The first such novel, Out of This Furnace, was written by Thomas Bell (real name Tomáš A. Belejčák, born in 1903 and died in 1961) and published in 1941.

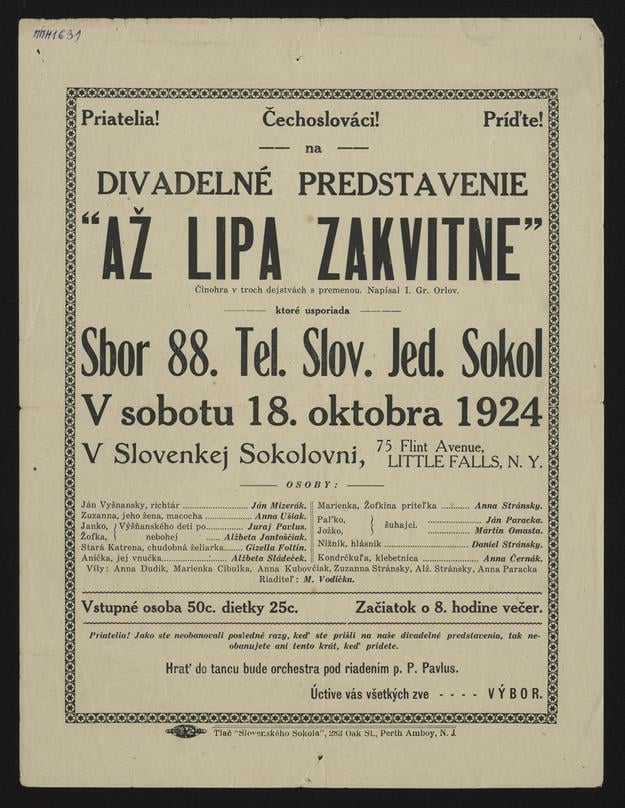

Film and theatre added to the cultural life as well. In January 1922, the film Jánošík, Captain of the Mountain Boys, enjoyed great popularity in Racine, Wisconsin. It was screened four times a day with an admission of 50 cents during the day and 75 cents in the evening. In the 1930s, a delegation of Matica Slovenská brought more films, including the popular The Earth Sings (Zem spieva) by ethnographer Karol Plicka, depicting rural life and folk culture. Volunteer theatre groups performed plays by Slovak authors. The performances were often accompanied by Slovak orchestras and choirs, and were followed by dancing.

The strong relationship of American Slovaks to their roots is also evidenced by the high attendance at Slovak celebrations and festivals. For example, on July 4, 1931, up to 6,000 visitors attended a Slovak Day in Owosso, Michigan. The programme of such events was rich - from church services in Slovak, speeches, and picnics to folk music, sports competitions and evening dances.

Slovak cuisine in America

Although not worn in their everyday lives, the traditional costumes inherited from their ancestors was particularly valued by American Slovaks.

Based on letters from their acquaintances in the US, they usually bought modern city clothes even before travelling to America or shortly after arriving. However, the traditional costume remained a part of households and was worn during celebrations, festivals, or weddings. Culinary traditions also remained alive. The first American-Slovak cookbook was published in 1892. Housewives would cook dishes known in their old homeland and passed these customs on to younger generations.

The preservation of traditions can be seen especially during holidays. At Christmas, there was no shortage of cabbage soup, roast potatoes and other traditional dishes from regions the immigrants came from. On ordinary days, Slovak women cooked temperate meals, depending on the season. Soups were frequent dishes - usually chicken broth with homemade noodles, on Sundays with liver dumplings; in the summer vegetable soups, while in the winter cabbage, bean or lentil soup.

Slovak women had to be inventive in some cases – they replaced the bryndza cheese in halušky with cottage cheese or sauerkraut, and they would fill pierogi with potato filling, minced meat, or various fruits and jams. They also prepared homemade noodles with poppy seeds or sugar and walnuts, and in the summer plum or cherry dumplings. Stuffed peppers or stuffed cabbage leaves were also popular. Slovak women often baked various types of cakes: stuffed rolls, doughnuts and also poppy seed, cottage cheese, apple and walnut strudels.

The Slovak emigration to the USA in the first half of the 20th century cannot be seen only as a change of residence, but as a complex process of assimilation in a new environment. Despite the gradual adaptation to the American way of life, they managed to preserve a significant amount of traditions from their old homeland, which significantly contributed to the strengthening of their national identity.

Slovaks managed to settle in the new country despite the many challenges they had to deal with. They were able to consolidate their roots by establishing their own communities, organisations and schools. With their presence and activities, they significantly contributed to the diversity and dynamism of American society.

Spectacular Slovakia travel guide

A helping hand in the heart of Europe thanks to our Slovakia travel guide with more than 1,000 photos and hundred of tourist spots.

Our detailed travel guide to the Tatras introduces you to the whole region around the Tatra mountains, including attractions on the Polish side.

Lost in Bratislava? Impossible with our City Guide!

See some selected travel articles, podcasts, and traveller info as well as other guides dedicated to Nitra, Trenčín Region, Trnava Region and Žilina Region.