The email that would change my life arrived one late afternoon in January 2024. Outside, the Anthracite Coal Region of eastern Pennsylvania was caught in the grip of winter—frigid winds, snow drifting in ragged bursts, and the bony outlines of trees fading into dusk. Inside, the house felt still, almost suspended in that peculiar hush that settles before something momentous.

Then, hope arrived—delivered by an unassuming subject line: “Levoča archive research done”.

Our genealogist in Slovakia had been working for over a year, tracing records that could determine our eligibility for Slovak citizenship by descent. My mother, Cynthia, and I had been waiting for this message with equal parts excitement and apprehension. With her standing beside me, I opened the email and began to read aloud:

“Hello, John. I am glad to let you know that I found the passport records of your great-grandmother.”

For a moment, silence. Then joy. My mother and I embraced as the magnitude of the news washed over us. Gratitude, disbelief, relief—all at once. The document the genealogist had found, my great-grandmother’s 1921 passport application from her home village of Žakarovce, was the long-sought key that would unlock our Slovak citizenship.

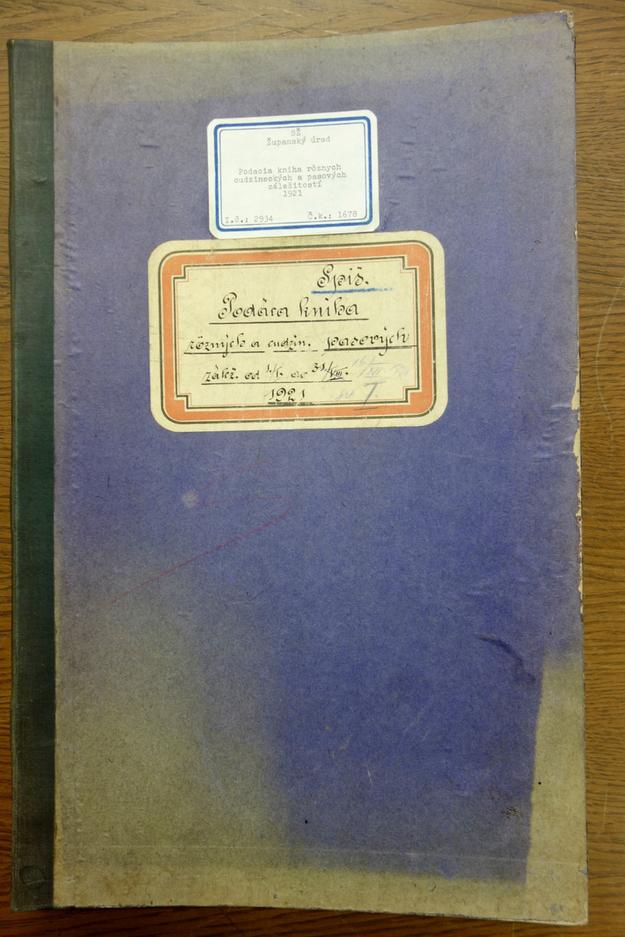

Czechoslovak passport records are among the most definitive proofs of citizenship under Slovak law, yet our genealogist had warned us that few survived from that era. Against all odds, there it was: the name Zuzana Majláth, clearly recorded in the Index of Various Alien and Passport Matters from historical Spiš County. That discovery transformed a distant hope into a living possibility. While further steps remained before my mother and I would formally become Slovak citizens in November 2024, we had crossed the most formidable threshold.

Tracing Zuzana’s path

Who was Zuzana Majláth? Though she became the cornerstone of my citizenship claim, I never knew her personally—she passed away in 1982, before I was born. Yet through this journey, I came to know her spirit.

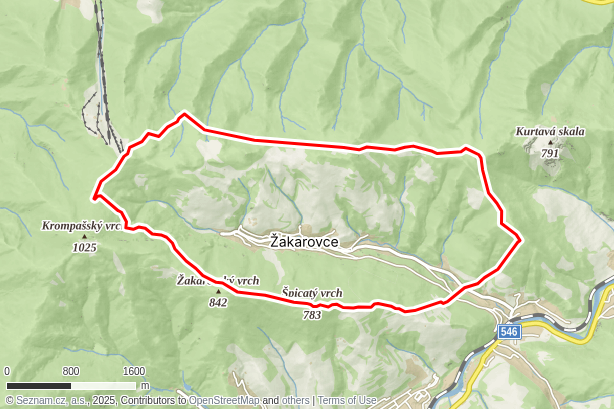

Born in 1896 in Žakarovce, a traditional mining village in Slovakia’s Gelnica district, Zuzana emigrated to the United States in 1921, part of a great wave of Slovaks seeking opportunity abroad. She settled near Hazleton, Pennsylvania—a city whose coal mines fed the furnaces of America’s industrial ascent, and whose streets became a mosaic of European immigrant life: Slovak, Polish, Italian, Irish.

There, Zuzana met and married Walenty Laskowski, my great-grandfather from Sromowce Niżne, Poland—a village perched just across the Dunajec River from Slovakia’s Červený Kláštor monastery. When I visited those same places in 2023, I couldn’t help but imagine my great-grandfather as a boy, watching raftsmen glide down the river, listening to tales of Cyprian the flying monk.

The immigrant’s strength

Life in the Pennsylvania coal towns was unforgiving. The mines demanded everything and returned little. To survive, families had to be as tough as the anthracite they mined. Zuzana embodied that grit. Family lore recalls her performing her own dental surgery when no doctor was available. On another day, when her grandchildren stumbled upon a rattlesnake, she seized a garden spade and decapitated it without hesitation.

Yet beneath her iron resolve lay tenderness. She baked bread and dumplings, took her grandchildren berry-picking, and carried a flask of cold coffee on summer days. The neighborhood children called her “Baba”. Through her stories, cooking, and customs, she kept Slovak traditions alive long after leaving her homeland.

There’s one tale I particularly love: Zuzana once told her children that her sister, Justína, had planned to emigrate with her but lost her nerve at the last minute. Later research proved that Justína never existed. Still, I like to think that story says something true about Zuzana’s nature—her flair for drama, her imagination, her way of turning hardship into legend.

Coming full circle

My search for Slovak citizenship began as a legal process. It became something far greater—a rediscovery of belonging. I suspect many people feel this same pull: the need to understand where we come from, to locate ourselves in the long thread of ancestry and story.

When I finally held my Slovak passport, nearly a century after Zuzana applied for hers, I thought of her courage—the choices that set this entire chain of events in motion. And I thought of my mother, who shared this journey beside me every step of the way.

Our story is, at heart, a circle completed. From Žakarovce to Pennsylvania and back again, from one Zuzana’s ink on paper to another’s hands holding a passport. A testament to endurance, love, and the invisible threads that bind families across time and continents.