“The Taste of Power” was not written to become a masterpiece.

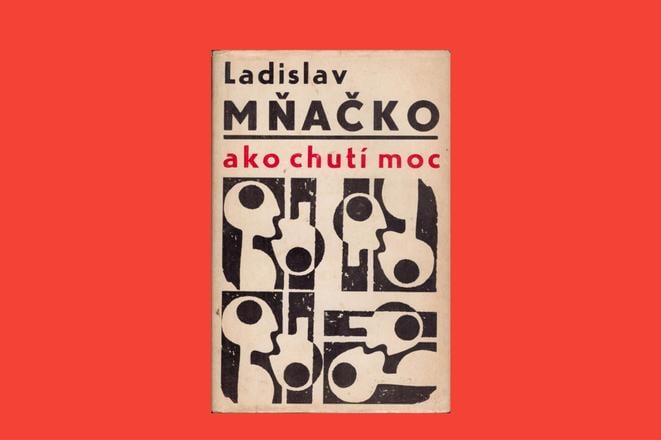

For its author, Ladislav Mňačko, the book was purely a political pamphlet wrapped in a novel, a biting criticism of the communist regime. Published in 1968, and banned soon after, the novel gained in importance after the fall of communism in 1989 in what was then Czechoslovakia, and later in independent Slovakia. “The Taste of Power” (Ako chutí moc) has become a timeless literary work, required reading in Slovak secondary schools, and a mirror held up to any politician who wields power.

In his book, Mňačko, a renowned Slovak writer and journalist who endured Nazism and turned from being a fervent communist into a fervent critic of the totalitarian regime, examines the impact of power on an individual.

The novel is set in communist Czechoslovakia in the 1950s, and takes place during a three-day state funeral for an unnamed communist official. Frank, a well-known photojournalist, describes the dead man and, in more detail, his coffin. He takes on the job of narrator, while the deceased man – despite his death – is the main character.

“A dead man was lying on a catafalque, wrapped in black cloth, his legs facing the entrance to the mourning room,” reads the opening line of the story, piquing the reader’s interest from the start.

Red street

Born on the Moravian-Slovak border in 1919, three months after the birth of Czechoslovakia, Mňačko’s family decided to move to Turčiansky Svätý Martin, now known just as Martin, a town in central Slovakia that was a cultural hub for Slovaks, soon after his birth. Here he grew up in the community of poor blue-collar workers on what was then Marx Street. This environment shaped Mňačko’s social-democratic view of the world, according to writer Jozef Leiker, who has authored two books about Mňačko’s life.

He studied to become a pharmacist, a job that he never enjoyed.

With the demise of democratic Czechoslovakia in 1938 and the corresponding rise of fascism, Mňačko decided to flee the wartime Slovak state, which was a collaborator of Nazi Germany, towards the Soviet Union. He was caught and taken to a forced labour camp in the Netherlands, from where he managed to escape. He later joined insurgents in Nazi-occupied Moravia and fought against the Nazis.

After the war, the communists gathered strength in the re-established Czechoslovakia (finally taking power in a putsch in February 1948). In 1945, Mňačko joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and started working as a journalist for Rudé právo (Red Justice), the official newspaper of the party, in Prague.

But Mňačko’s political views evolved as the communist regime revealed its true self and unleashed unrestrained terror and lawlessness. “He spent 11 years as an obedient communist, 11 years as a communist critical of the regime, and 36 years as a harsh anticommunist,” said Leiker, who always considered the talented Slovak writer to be a social democrat deep in his heart rather than a communist.

Fabricated political trials, among other injustices, turned the prominent journalist into a vocal critic of the inhumane regime. The Slovak author wrote about some of the horrors committed by the regime in “Delayed Reports” (Oneskorené reportáže) in 1963, which sold tens of thousands of copies. After being threatened with prison time by a top communist leader, Mňačko moved to Bratislava.

There, he joined the Pravda (Truth) daily and wrote for other papers as well.

Emigration

When Czechoslovakia, following the Soviet Union’s example, sided with the Arab countries during the Israeli-Arab conflict and cut diplomatic ties with Israel in 1967, Mňačko protested by fleeing to Israel. During this time, he was stripped of his Czechoslovak citizenship and expelled from the Communist Party. He spent almost a year in Israel before deciding to return in 1968.

“I came back only to leave again, perhaps forever,” he wrote in his book “Seventh Night” (Siedma noc).

Following the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops in August of the same year, he fled to Austria, fearing persecution by the Soviets for his past actions and opinions.

Subsequently, the regime banned his books.

Mňačko continued writing in Austria. By then, he had earned the nickname “the red Hemingway” in the West. He returned to Czechoslovakia after the fall of the regime in 1989, eventually settling in Prague after the breakup of Czechoslovakia in 1993, a development he did not support.

What “The Taste of Power” tells the world

In “The Taste of Power”, which was published almost a decade after his famous war-inspired novel “Death Is Called Engelchen” (Smrť sa volá Engelchen), Mňačko establishes a second line of storytelling – Frank’s memories of the deceased statesman and their long friendship – seamlessly woven into the three-day funeral narrative.

Frank’s thoughts and memories of the unnamed official increasingly overwhelm the real-time storyline of the funeral as the narrative progresses.

Throughout the novel, the narrator examines the rise and fall of the deceased statesman. He recalls his dear friend’s bravery during partisan operations in the Second World War and his passion for the revolution, which slowly morphs into blind compliance with the regime in pursuit of power and benefits. The statesman is completely stripped of his personality, morality and values as the story progresses, serving as a case study in the way that power corrupts. Divorcing his loyal and kind wife, abandoning his guiding principles, and harming those whom the statesman once held dear, Mňačko delves into a topic that was relevant long before this story was published – and remains so today.

The life and death of the statesman serve as a powerful metaphor for a phenomenon still observed among political figures who rise to power today: candidates who initially seem honest and eager to improve their countries are often warped by their experience of power, forming alliances with those they once resented and abandoning their previous concern for the public. Men wage wars in the name of prestige at the expense of innocent civilian lives.

While “The Taste of Power” lacks a traditional storyline, Mňačko’s philosophical approach, combined with the narrator’s assessments, scrutiny and praise, creates two contrasting perspectives: the statesman’s life and actions, and Frank’s evaluation of his situation, underscored by resentment at the statesman’s later, power-hungry behaviour. This seems to parallel their fictional relationship when the statesman was still alive.

“Frank became his trusted companion, unofficial advisor, his black-and-white conscience,” Mňačko writes, describing their coexistence before the statesman abandons their friendship.

After examining the anecdotes that Frank presents to the reader about the statesman, paralleling the descriptions of his overly organised and rehearsed funeral service, Mňačko concludes the novel with Frank’s final evaluation of the statesman’s life.

As he lies sleepless next to his wife, Frank ponders the purpose of his friend’s life, asking, “For what was all that power that you gained? How did it taste? What did it help you to do, what did it solve, where did it lead you? Once you were healthy, powerful, full of enthusiasm. And happy. Did your happiness intensify?”

Mňačko, who died while writing his memoirs in 1994, reminds readers that power is neither good nor bad.

“Power can become good, power can become evil; it depends on who wields it.”

Ladislav Mňačko’s book “The Taste of Power” was published in 1968. (source: TSS)

Ladislav Mňačko’s book “The Taste of Power” was published in 1968. (source: TSS)

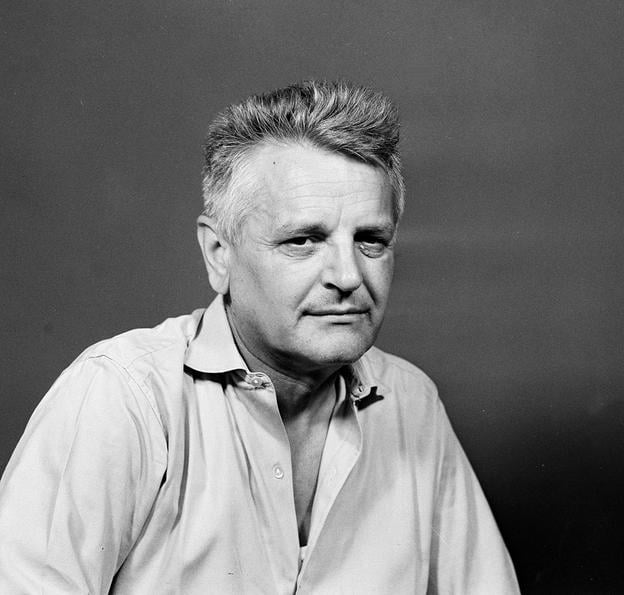

Ladislav Mňačko, as portrayed in July 1968. (source: TASR)

Ladislav Mňačko, as portrayed in July 1968. (source: TASR)

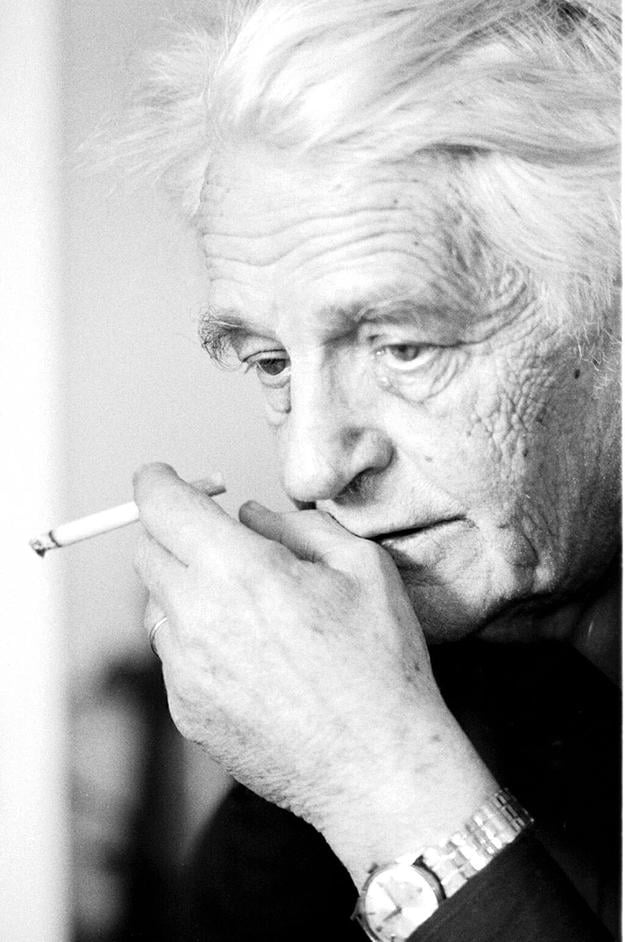

Slovak writer Ladislav Mňačko died on February 24, 1994. The picture was taken in 1991. (source: TASR)

Slovak writer Ladislav Mňačko died on February 24, 1994. The picture was taken in 1991. (source: TASR)