The interview, originally in Slovak, was first published in the fjúžn magazine.

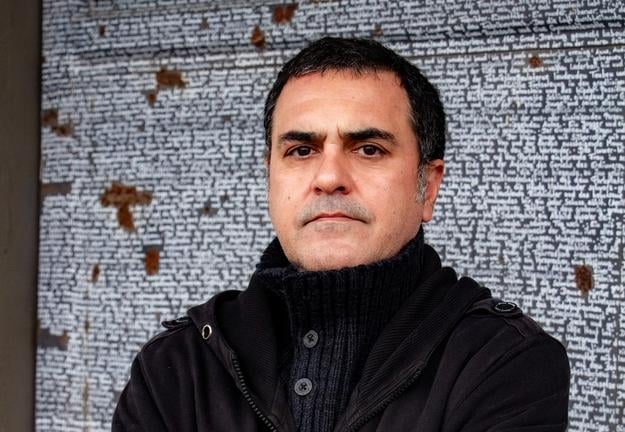

Farhad Babaei (born 1977) is an Iranian writer. He has written and published two collections of short stories and more than ten novels. Over the past decade, most of his books have been banned due to heavy censorship, and his name has appeared on the blacklist of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. He was never allowed to officially publish his books in Iran, although some of them were circulated as samizdat editions.

Several of his short stories and articles have been published in cultural magazines and literary websites abroad, while some of his novels have appeared through English-Persian publishing houses in London and Germany. Earlier this year, one of his novels was translated into German. He is also the author of two short documentary films made in Iran and Germany.

Despite numerous threats, constant censorship, interrogations and arrests, he refused to allow any control over his writing. Determined to continue working freely, he applied in 2019 to the international organisation ICORN (International Cities of Refuge Network) for temporary refuge.

He found that refuge in October 2023 in Bratislava, which selected him as its first ICORN resident. The Slovak capital thus joined the network of cities offering temporary shelter to persecuted writers and artists. Bratislava’s entry into the ICORN network was made possible through the cooperation of the Milan Šimečka Foundation, the City of Bratislava, and literarnyklub.sk, which coordinated the residency.

What are your stories about?

In recent years, I have been writing about different families, their members and relationships. Earlier, I focused on people who feel lonely even though they have families or friends. I am particularly interested in human rights restrictions, especially those affecting Iranian women. I try to shed light on what they go through in a dictatorial country in the Middle East — on the injustice they face.

For example, when a woman in Iran wants to divorce her husband, it is not at all simple. The man’s demands and needs always come first. The woman is secondary, even when she has objective reasons for divorce — such as her husband’s infidelity.

You explore this topic further in your unpublished story Bahram’s Condition for Nahid.

Yes. Nahid accidentally finds an erotic video on her husband Bahram’s phone, in which she can see an unknown woman’s face and hear his voice. She confronts him and files for divorce. However, he sets a condition — despite the fact that she is in the right — that he will grant her a divorce only if she sleeps with him one more time. Nahid refuses.

How does it end?

The ending is open — I leave it to the reader. Through this story, I wanted to highlight the absurd conditions Iranian women face. Once a couple is married, only the man has the legal right to file for divorce.

Women cannot even travel abroad without their husband’s permission. They cannot apply for a passport unless their husband is physically present.

Where do you find inspiration?

This story reflects the real experience of a friend of mine. I wondered what happens to a woman whose husband imposes such conditions.

But I also see similar situations in the lives of my sister, mother, aunts and friends. The police intimidate women to stop them going out without a hijab. At one secondary school, officers even stormed in using tear gas to frighten the girls — many ended up in hospital.

In the metro corridors, men are stationed to check how women are dressed. If a woman’s hijab is missing or “worn incorrectly”, the violence from police can be so severe that it may lead to death — as in the cases of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini and 16-year-old Armita Geravand.

Yes, Mahsa Amini’s case triggered huge protests in the country. Many young women took to the streets. You joined them as well.

In Iran, it is forbidden to write about relationships or intimacy — you are not even allowed to mention having a pet at home. How did you feel when the Ministry of Culture first asked you to remove certain passages from your book?

I grew up in a society steeped in censorship. Early in my career, I didn’t fully realise how deep it went. My goal was simply to publish at least one collection.

The first two books I wrote were automatically sent by the publisher to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance for approval. A year later, they told me that one of the stories — 60 pages long — could not be published. It was completely deleted. In the second book, they objected to two stories and demanded I remove words such as embracing, kissing, or dancing. It was absurd — I had written an ordinary story about a middle-aged man.

In the end, I decided not to publish them.

If you wanted to publish in Iran without censorship, you had to resort to samizdat, foreign publishers, or the internet — but each came with serious risks.

Yes. Still, I cannot imagine doing anything else. I love writing.

What does underground publishing look like in Iran?

I studied graphic design, so I designed the books myself. I didn’t need a publisher.

I found a printing house that didn’t ask to see a licence. I told them it was a school project. I printed about 50 to 100 copies — without barcodes or prices — and covered all the costs myself.

On social media, I simply announced that I had released a new book, available at selected cafés — owned by my friends.

You were interrogated and even arrested because of your work.

Yes, first because of my novel Mr Shapour Grayeli’s Family, which had been approved by the ministry and published legally. Eight months later, Fars News Agency (a right-wing outlet close to the Iranian regime) published a false article about the book, accusing me of depicting a sexual relationship within an Iranian family.

I expected to be arrested. When my friends read the article, they called me in fear. When Fars News Agency writes about someone, it usually means that person will soon be taken in. The agency has enormous power — even the ministry fears it.

The book was subsequently banned, and my publication licence was revoked.

Later, I was arrested again following an article in another right-wing newspaper, Keyhan — a particularly dangerous one. This happened a year after I had submitted another book to a publisher. After three or four months, the ministry banned it without explanation and erased the entire text. The article accused me of criticising former Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini and other regime figures. I was interrogated over a book that had never even been published. It was pure paranoia — a nightmare.

Was it difficult to get to Slovakia?

I waited three or four years for the opportunity — delayed by the pandemic.

Then, one day, I received an email from ICORN saying they had started cooperating with a new partner city — Bratislava — which had selected me as its first resident. Together with the Literary Club, we began preparing the necessary documents and an invitation letter. I submitted them to the Slovak Embassy in Tehran, and about ten days later, I received my visa.

Everything happened within three months of the first contact. It was quite fast — and on 1 October, I arrived in Bratislava.

How did you feel when you arrived?

On the first day, I thought it was just a dream. This was the first time I had ever managed to leave my country.

You had never been abroad before?

No, never. Even a short trip to Turkey for three or four days is very expensive. European and more distant countries are simply unaffordable for ordinary Iranians. And you need a visa — which is difficult to obtain. Iran must be convinced that you will return.

What was it like leaving for Slovakia?

I was very nervous at the airport. Security officers at the final gate checked my laptop and entered my name into their system. I didn’t have any documents proving property ownership, which could have raised suspicion that I might not return. One wrong move, and they could have cancelled my ticket and sent me straight to prison. I would have had to justify my journey to Europe before a court.

Fortunately, none of that happened.

When did you first feel relief?

On the plane. Looking out at the dark sky, I saw a flash of light through the clouds and glimpsed a country below. I thought: This plane is flying to a land where freedom of speech exists — and it won’t turn back.

I wasn’t just flying to Bratislava. I was flying towards freedom.

What are your plans for the coming months in Slovakia?

Most ICORN residencies last two years, but mine is for one year so far. I’m a little anxious about that, but I hope it will be extended for another year.

After that, I’ll have to decide whether to stay in Slovakia long-term or move to another European country. I’m 46 now, and that’s old enough to leave behind life in a country like Iran. I tried everything to be able to write and publish there — but it wasn’t possible. I don’t want to go back.

As a human being, I want to experience something other than fear — fear of religion, or of the Iranian regime.

If I were to return, I would be arrested at the airport immediately. I am that “dangerous writer” on the blacklist.

When we last met, you mentioned wanting to try things that don’t exist in Iran — like McDonald’s or Starbucks. Have you tried them yet?

Not yet — but I plan to.

Farhad Babaei (1977)

Began writing in the late 1990s, starting with short stories and expanding into novels and screenwriting.

Published his first short story collection, Her Lover Azrael, in 2006, exploring the lives of lower-middle-class couples through magical realism.

Authored several works including Nowruz, Tower, Graffiti, Jamming, Demon Land, The Condition of Bahram for Nahid, and Disintegration.

Many of his works were censored in Iran for addressing themes such as war, protest, sexuality, and religion.

His novel Mr Shapour Grayeli’s Family (Cheshmeh Publications, Tehran) was one of few to pass censorship and sold out its first print run.

Creator of the short film Period (2010) and screenwriter for short documentaries including Density of Emptiness by Shirin Barghnavard.