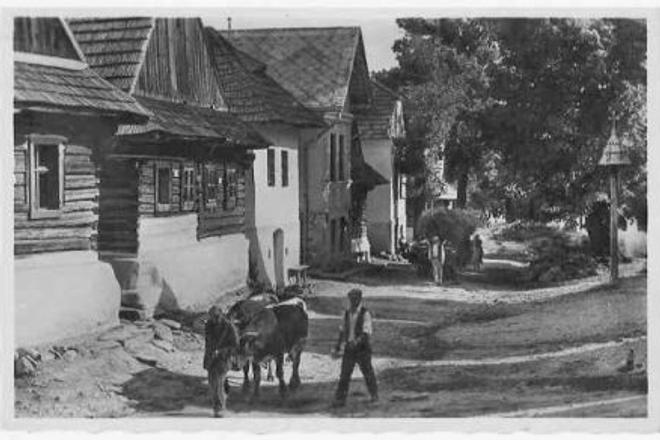

Looking at the village of Bobrovec in the Liptov region, one can understand why the Slovak countryside struggled so much with fires in the past. Dwellings, especially in the poorer mountain regions, used to be constructed from wood, and even those made from bricks often had a wooden roof.

Fires had fatal consequences for villages and towns. For example, in Oravský Biely Potok, fires were so frequent and intense that today only a few wooden blockhouses are left and, more significantly, the village lost its original street plan.

Due to frequent fires, villages started erecting alarm bells. However, these structures did not become widespread until after the authorities declared them mandatory.

In 1751, Maria Theresa issued the so-called Fire Patent, which mandated the construction of bell towers, particularly in settlements without churches. These towers, along with night watchmen—also a new concept—were intended to alert people in case of fire. In villages with churches, the church bells could serve this purpose.

The patent also introduced basic fire prevention principles for house construction, such as the requirement for brick chimneys and wells, along with fundamental rules for firefighting.

Bell towers of various shapes and sizes started popping up all over the Slovak countryside after the Fire Patent. In Slovakia, more than 200 alarm bell towers are registered today, several of which are protected monuments, especially the wooden ones.

In this postcard, published around 1940, we can see an alarm bell mounted on a pole on the far right.

This article was originally published by The Slovak Spectator on September 15, 2014. It has been updated to be relevant today.

In this postcard, published around 1940, we can see an alarm bell mounted on a pole on the far right. (source: Branislav Chovan)

In this postcard, published around 1940, we can see an alarm bell mounted on a pole on the far right. (source: Branislav Chovan)