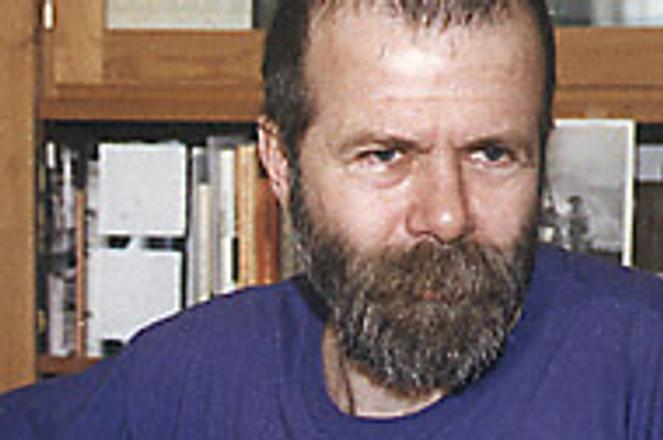

Martin Klein may be headed to prison for an article he wrote in 1997 which a court said libelled the Catholic Church.photo: Ján Svrček

Slovak journalist Martin Klein is a self-styled lone wolf. He was never a boy scout, nor did he serve in the army, and he finds the thought of being lumped into any group of men - especially a group of convicted criminals - intolerable. Nevertheless, he has elected to go to jail rather than pay a court fine, and says that if he can do his time in solitude, he won't mind too much.

"I've always been something of a loner," he says.

Klein, 54, doesn't need to be behind bars to feel isolated, but that's where he may be in the coming months. After being fired by Radio Free Europe Prague in 1997 for writing a controversial article for the Slovak weekly Domino efekt, Klein has been unable to find regular work for four years, and in June 2000 was convicted of libel by a Slovak court for the article and sentenced to pay a 15,000 crown fine or spend a month in jail. Since losing an appeal in January, Klein has vowed to go to prison rather than pay the money.

"One, I don't have the money. Two, I don't think I should go to jail for expressing my opinion," he says.

Klein's trouble started in March 1997 when Slovak Catholic Archbishop Ján Sokol appeared on state-run Slovak Television calling for a ban on the Hollywood film The People vs. Larry Flynt because its promotional poster - an actor posing as a crucified Christ in a woman's crotch - degraded the crucifix.

Klein, a rabid anti-communist and an ardent opponent of former Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar, was outraged that the Archbishop, whose name had appeared on a list made public in 1992 of people who had worked with communist Czechoslovakia's secret police (known as the ŠtB), was moralising to the nation on Slovak Television, which he says was controlled by Mečiar.

This article, published in 1997, landed Klein in hot water with the Catholic Church, the courts and his fellow journalists.photo: Domino efekt

Having settled into a new job at Radio Free Europe as a political commentator and film critic, Klein couldn't resist when Peter Schutz, editor-in-chief of Domino efekt (an intellectual political weekly and precursor to today's weekly paper Domino fórum) asked him to write a response to the Archbishop for his commentary page.

"There were plenty of articles calmly refuting the archbishop," says Klein. "I wanted to say it more radically, to hit him so that he would remember."

Both the Archbishop and the media community soon had reason to remember Klein. The 800-word article he wrote that appeared in the March 28 - April 4, 1997 issue of Domino efekt contained seven Slovak vulgar expressions for the act of sex; writing about Sokol in an abstract fashion, Klein also made reference to a scene in The People vs. Larry Flint in which it is suggested that an American television evangelist has had sexual intercourse with his mother. Klein's piece also questioned why "decent Catholics" did not leave an organisation headed by a communist collaborator.

"I used some ideas from the movie, but the point was that a person who worked with the Communist secret police had no right to lecture the nation on movie posters," says Klein.

Klein admits the style was harsh; others believe he crossed the lines of taste and ethics.

"I thought the article was disgusting," said Štefan Hríb, editor-in-chief of Domino Fórum, which was created when Domino efekt folded, and a former colleague of Klein's at RFE. "That sort of language would be appropriate for a novel, but not for a newspaper."

Klein's former colleagues have praised his skills, if not his judgement.photo: Ján Svrček

Archbishop Sokol did not sue, but two Catholic organisations complained to the Slovak Attorney General's Office, which charged Klein with libelling the Catholic faith. In Slovakia it is illegal to libel "a race, nationality, or religious faith".

In The People vs. Larry Flynt, American pornography mogul Larry Flynt was sued because of a cartoon published in his Hustler magazine that suggested that preacher Jerry Falwell had had sexual intercourse with his mother. The court in the Flint case ruled that libel laws did not apply to satire, accepting the argument of Flynt's lawyers that setting boundaries for satire was "a matter of taste, not law".

Klein's lawyers, however, did not stress that the text of his Domino efekt piece - which begins "As is commonly known, the earth is flat" - was satiric. They argued that libelling a leader of an organisation was not the same as libelling the organisation itself, and that the sentence "I don't understand why decent Catholics do not just leave an organisation headed by such an ogre" could not be libellous because it was not a statement of fact.

The court disagreed. It ordered Klein to pay a 15,000 crown fine or spend a month in jail. Klein lost his appeal in January 2001 to a regional court. In the middle of March, Klein received a notice saying he had to pay the fine in two weeks or be taken to jail. He allowed the two week period to expire and is waiting to hear from the police.

The high-profile media case that wasn't

When he lost the appeal, Klein expected that the Slovak media would circle its wagons around what he considers an important free speech issue. But since then Slovakia's 30 most popular dailies and weeklies ran a total of only four articles, three opinion pieces and one letter to the editor on his case.

Klein calls the light coverage "scandalous", and accuses his former colleagues in the Slovak media of being "bloody cowards".

But some leaders in the media say Klein is overestimating the importance of his case, and portraying himself as a martyr over what was, they say, a slap on the wrist.

"To be honest, there are many more important issues right now in Slovakia for the media, such as the pressure on journalists from publishers and advertisers, and libel cases taken to civil court," said editor-in-chief of the Slovak daily Sme Martin Šimečka. Sme, with three articles since the appeal in January, has covered Klein's case more than any other.

"The ruling was ridiculous, but not dangerous to free speech. The fine was really only symbolic. It would be quite easy to pay this amount of money," he added.

Alexej Fulmek, the head of the board of directors for Grand Press (which publishes Domino fórum, Sme and The Slovak Spectator) has even offered to pay the fine.

"That's not the point, the point is that I shouldn't have to pay anything," says Klein, who likens his willingness to serve time in prison on an issue of principle to the penalties paid by former dissidents under Czechoslovakia's communist regime. "None of them [dissidents] had to go to jail," said Klein. "They could have gone to Vienna, just like I could pay the fine and avoid going to jail."

Other media experts say that the absence of media reaction to Klein's case may be due to general acceptance in Slovakia of limits on free speech.

"For 150 years since the Austro-Hungarian empire, we have lived with limits on what we can say publicly about others," said director of the Syndicate of Slovak Journalists Ján Füle. "Personally, I don't believe freedom of speech means anybody can say anything they want about anybody else. If not the courts, who is going to decide where the boundaries are?"

"I don't think this is a case of freedom of speech," added Hríb. "I think it is a case of whether or not we are free to use brutal language in journalism".

Even Klein's lawyer, Ernest Valko, said that his client had broken the rules of journalistic ethics. Representatives from Valko's law office added that they had considered appealing to the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights because they believed Klein had not committed a punishable act, but were discouraged by the poor success rate of others who had taken similar cases to the court.

A media pariah

In Martin Klein's two-room Bratislava flat - along with piles of books, a computer, black and white art photography posters and a three-month old baby - there is a wooden chair. Klein purchased the chair for $500 (over two times the current Slovak average monthly salary) two days before writing the Domino efekt article, and two months after starting as a full-time reporter at Radio Free Europe. The RFE stint was a dream job for Klein, who emigrated to Germany in 1985 partly because "I always wanted to be a journalist, but a decent person couldn't be a journalist under Communism".

Klein could afford to splurge on furniture. RFE had agreed to pay him $38,000 a year (almost 14 times the current average annual Slovak wage) and cover his rent on accommodation in the centre of Prague. But the job and the money were short lived.

After the Sokol article was printed, Domino efekt was inundated with critical letters to the editor. State-run Slovak Television did a 30 minute piece on the controversy, which it aired in prime time. When RFE's management got wind of the coverage, they fired Klein for "unprofessional conduct", saying in a letter to Klein obtained by The Slovak Spectator that his article had created a "storm of protest" with which they could not allow RFE to be associated.

Klein's rebuttal that the text had been artistic rather than journalistic was to no avail. Although he remained unemployed for the next several months, he expected his career to rebound.

"I laid low for a while," says Klein. "My main concern was that Mečiar could use the case against the opposition [Klein says Domino efekt was an opposition newspaper]."

By fall 1997, Klein had found a job with an Austrian press agency, but was soon fired for holding up a sign that said "Down with Mečiar" in front of a Slovak Television camera broadcasting live at a Mečiar press conference in the run-up to September 1998 Slovak national elections.

"This TV station had made a hash out of me months earlier, and had never asked for my or anyone else's opinion," explained Klein. He admits that his press conference behaviour was unprofessional, but says he was surprised the gesture wasn't more appreciated.

"Slovak Television was a scandalous station," he says. "Someone should have given me a medal."

Klein thought his problems finding work would disappear after "we [the political opposition] won" the national elections in fall 1998, but he went without a job until June 1999, when Slovak Television hired him to work on the nightly news. He was given a test run that August as news director, but clashed with a reporter on the first day over a report on the World War II bombing of Nagasaki; he was demoted to the position of news correspondent within a month. His contract was not renewed the following June.

Since then, Klein has applied to seven Slovak media, but has not received long-term or full-time work. Slovak Television signed him to a three month contract at the beginning of this year to make two weekly programmes about tolerance. He is unsure whether they will renew his contract.

"It's a shame that he hasn't been working regularly," said Peter Schutz, who as editor-in-chief of Domino efekt in 1997 was responsible for publishing the infamous Sokol article. "There wasn't a better Slovak reporter covering foreign affairs [back in 1997]."

Klein maintains that the Slovak media is afraid of him because of the 1997 article and subsequent court case. But those that have known him for a long time say his behaviour since the article was published, especially the Slovak Television press conference incident, has derailed his career.

"He has submitted material to me, but it was unusable, as though he were trying to push me into a corner, to make me be the bad guy by having to reject it," said Sme's Šimečka. "Klein is technically very skilled, but he abuses his talent. He is provocative in a way that plays games with the reader."

Domino Forum's Hríb said that Klein had also sent him questionable articles, including an interview - with himself. "In the interview he asked himself a question about something, and then replied to himself, "How can you ask me such a question?'" said Hríb.

"I am a good journalist, and Hríb and Šimečka know it," says Klein, who, though bitterly disappointed with his court case and with his plummeting career, would like to stay in Slovakia and continue as a journalist.

"A friend asked me in 1997 what I wanted out of life. All I want is to live in a normal country, where you don't go to jail for your opinions, and if you are a good journalist you get a job," he said.

"If nothing had happened in 1997, I'd be a star journalist by now."