Many of these rituals were influenced by superstition and connected to the agricultural calendar. They are part of Slovakia's rich folklore, and much research has been dedicated to their documentation.

According to the book Slovakia: European Contexts of the Folk Culture (Veda, Publishing House of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, 1997), on the Saturday before Easter Sunday it was customary to bring food in baskets to church and have it blessed. The food was then eaten after the service and throughout the holiday, as a reward after the 40-day fast of Lent. There were usually sausages, smoked meat, cheese, cakes, and eggs.

Eggs are a traditional spring food all over the world, and are considered to be a symbol of new life and fertility. In Slovakia, they would be eaten hard-boiled or as part of another dish. In many villages, sausages and smoked meat were also an important part of the Easter meal, as were alcoholic drinks.

Meat had a significant position in Easter meals, with roasted lamb or kid the most traditional dishes. During periods when sheep breeding was slow and young animals were not so easy to come by, meat would be replaced with a cake in the shape of a lamb. This was then used to decorate the Easter dinner table.

The consecrated Easter food was considered to have healing or magical powers, and some leftovers were kept for a long time and used in certain rituals. For example, breadcrumbs were sometimes put into the ground when the fields were first ploughed. In some regions, people brought food to the graves of dead relatives, or at least visited the cemetery at Easter.

The Slovak Spectator asked three people from different parts of Slovakia about the local traditions connected to the holiday of Easter.

Nadežda Varcholováfrom the Museum of Ukrainian-Ruthenian Culture in the eastern city of Svidník speaks about the customs in the border region and the Ruthenian ethnic minority:

Maundy Thursday, just before Good Friday, was a day believed to be in the power of witches, and the traditions resembled the holiday of St. Lucia [on December 13]. People wanted to protect themselves from the magic, so they drew crosses with sanctified chalk on the doors of houses. To protect the animals, people strewed poppy seeds in front of cowsheds, because they believed that witches would have to pick up all the seeds before they could enter. On Thursday the church bells were rung for the last time, then they were tied together and from Friday onwards, people shook rattles to call people to church.

On Friday, early in the morning, girls went to comb their hair naked under a willow tree, with the hope that they would have long, beautiful hair.

The Easter holiday is called Paska in our region, which is also the name of a round cake eaten for Easter. It was usually baked on Saturday, and there was a superstition that if the cake broke during baking, it meant there would be a death in the family.

On Easter Sunday, the paska and other food were brought to the church to be sanctified. Leftovers from the festive meal were preserved and then used for other rituals, for example to ensure a rich harvest.

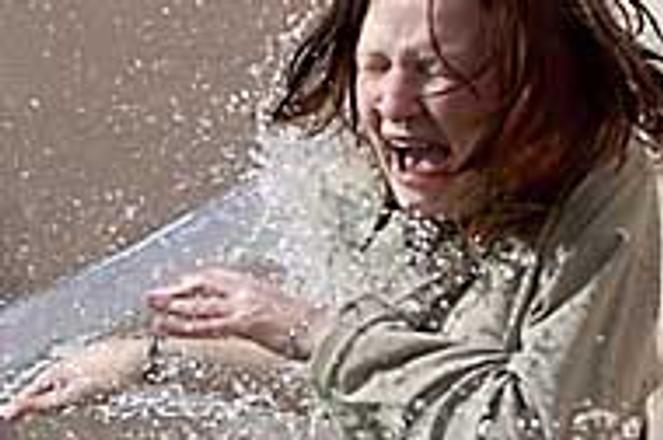

On Easter Monday, as in all other Slovak regions, girls were soaked with water by boys and men, usually in a creek or with buckets of water. The difference in our region is that we don't have the tradition of the Easter whip. It's not common in eastern Slovakia, and not among the Ruthenians and the Ukrainians anyway.

Ľuba Sýkorová,ethnographer at the Kysuce Museum in Čadca describes the rich Easter heritage of the northern Slovak region of Kysuce:

In the Kysuce region, eggs were used for various rituals connected with agriculture, but unlike in other parts of Slovakia, they were not brought to graves of relatives. The colours of the decorated eggs played an important role: The eggs shouldn't have been white, because that symbolised death. They were either red, symbolising love; or green, as a message from a girl to a man that he had a chance with her; or blue, if a girl's parents decided who she was going to marry.

The soaking and whipping of girls are very common in all towns and villages. Water symbolised life and the willow branches were chosen because it's the tree that wakes up first in the spring.

The modern version of the Easter 'bathing' is that men pour both water and perfume on the girl. But the tradition of giving an egg as a gift is slowly disappearing; most of the Easter eggs are used for decoration only.

Izabela Danterováfrom the Museum of National Geography in Galanta explains the Easter rituals practised in the region southeast of Bratislava:

For the region of Žitný ostrov, the use of coals that were sanctified during mass on the Saturday before Easter was typical during the Easter holidays. Housewives took a few pieces of coal from the church and then lit a fire from them in their home. This fire was assigned purifying powers and people believed that it would protect their house from evil and diseases.

In this region, the food was blessed on Sunday not Saturday, and the egg was eaten first and in a special way: It was cut into as many pieces as there were family members. This symbolised the unity of the family. It was said that people who ate an Easter egg together would never forget each other. Portions of the special dishes were also given to cattle and thrown into the well, which was supposed to ensure that the water tasted good.

Slovak Easter calendar

Zelený štvrtok (Green Thursday) - Maundy Thursday

Veľký piatok (Big Friday) - Good Friday

Biela sobota (White Saturday) - Holy Saturday

Veľkonočná nedeľa (Easter Sunday) - Easter Day

Veľkonočný pondelok - Easter Monday

IS SOAKING girls with buckets of water fun, or a subtle form of male dominance? (source: TASR)

IS SOAKING girls with buckets of water fun, or a subtle form of male dominance? (source: TASR)