Dezső Kóhn had too many memories. They were sticking out of his ears, his pockets, and the sleeves of his grey checkered jacket that he would only take off in the evening before he went to bed.

If he could, he would have leaked the memory of the Mlynská Kolónia in Lučenec that was turned into a Jewish ghetto in 1944 and from where he was taken later with other men for forced labour, like urine.

Kóhn brought up my father. That small fragile man had memories heavier than bones in his body, so his knees would bend and people would think he was drunk. And he often was. The old Kóhn gave my father his roots, so deep that he was never able to leave Lučenec.

He preferred to pass on only happy memories to my father. But there were pitifully few of those. In the favourite memory of Kóhn’s, uncle Poldi bácsi was selling watermelons. From time to time he cut one to pieces and spread them on the table next to a pile of pumpkins in the yard. He sat down, and pretended he was dozing off, while children came to steal pieces of watermelon from the table.

Dezső had no one to share his childhood with, that time when there was still hope that Lučenec was an amicable town. Many of his neighbours whom he knew since he was small, did not return after the war.

Cemetery without memories

He was unable to get rid of the past in a way his wife, Rézi, who as a Catholic, devoted the unbearable things to God. I think that after the Holocaust Dezső had no idea anymore where to seek God.

Perhaps Poldi bácsi would have advised him how to be a Jew in a world where they tore people up by the roots and dragged them around countries of desperation only to throw them into that empty hole that was left after them, to try and have a life.

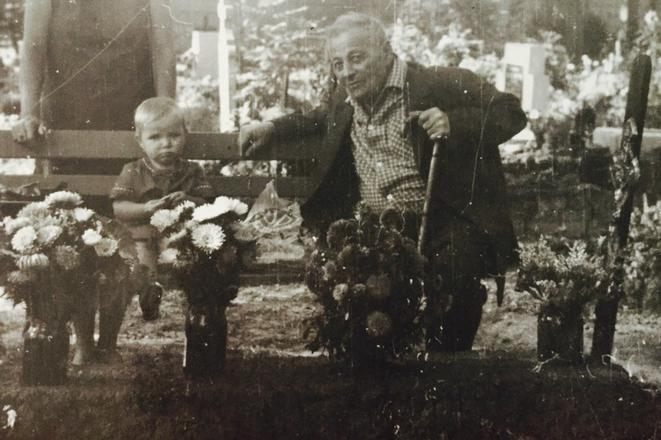

Great-grandfather often used to take me to the Lučenec cemetery. We used to sit there for hours. Close to a shabby fence dividing it from the Jewish cemetery. We never went there. I was a child, and not a fit audience for stories unlocked by cemeteries. I only remember the silence that I could not break with any amount of wailing to go home.

Too late

Today I know that the Nazis beat Dezső Kóhn so badly that he lost all his teeth. He slept in one room with the dead; and that was not the worst of his memories. Not even my father was able to collect all his heavy memories.

The memory he told us most often was the lightest one, that would make us laugh. One night, Dezső came home and something was moving under his shirt. He started complaining, what did you cook there Rezi, my bowels want to get out of my body - and something was really moving under his short. When the tension could not be escalated any further, he took a grass snake from under his shirt and put it in his grandson’s hands. It’s a harmless snake, let it out tomorrow by the river.

Dezső Kóhn was not the only one who never told his dark stories.“

Today I rake through old pictures and letters in the hope I will find something, perhaps one letter that was never sent, a card with notes, or a scrap from a diary that would tell me more about his darkest memory of the times gone by. However, part of the evil from those times remains. And that evil keeps fighting its way back to the surface, like muddy water that part of the nation still drinks from and thus nourishes the fascists.

Dezső Kóhn was not the only one who never told his dark stories.

Ari

Ari Rath, a legend of journalism, who had his country taken from him by the Nazis when he was a child, told stories also in the name of my great-grandfather. He told them in the name of all those who were unable to talk about the horrors, because they fused into one nightmare that paralysed the tongue.

When I met Ari in 2015 in the Café Landtmann in Vienna, he unwrapped one story after another, as if he spent his whole life preparing for the role of a storyteller. He said it was not a coincidence that he remembers many things clearly and he was allowed to live long enough to give testimony about the dark times.

Then he asked me about my family, about the names that my ancestors gave their children. About the scar on my arm, the memories from my childhood. I told him about Dezső Kóhn who did not leave me his stories. And he understood that.

He knew that talking about dark times is not like a few scattered sentences people share in social talks, about the children growing up and the parents keeping up, or about the holiday they are planning this year.

He also knew that we are forgetting to really listen. And this ability of ours, to listen and to understand stories, to live them anew with our close ones but also with strangers, will decide about our empathy and humanity in the future.

Departure

Let’s enter the people who might not be here in a few years, like we enter precious books, aware that sometimes a gentle gesture, a mere move of the hand, may tell more than ten sentences. Sometimes, a single sentence of theirs captures more of life than whole chapters in history books.

Ari told me in the spring of 2015 that his story remains untold, that it is open for us all who are still here. Open for us to add something, to show how decisively and resolutely we can say no to the evil that drips from everyone who toys with Nazism.

Ari Rath died on January 13, 2017.

He wanted us to learn from the stories he passed on to us as the heritage from those who could not talk about evil.“

Many felt they still owed him one big apology. Maybe in the name of humankind. But those who spoke with him understood that he did not expect us to apologise. He wanted us to learn from the stories he passed on to us as the heritage from those who could not talk about evil.

Let’s seek stories

People who know more about Europe’s dark times than just a few chapters from history books, are leaving. Those who saw the faces and gestures of desperation, who heard the cries of children, the wails of animals, smelled the stink of warehouses were people who were deposited like redundant materials, in the moments when part of humankind turned off its humanity like a lamp on a nightstand.

People who lost their closest ones and the luxury of faith that the world is alright and that the worst atrocities are only the perversions of history long gone.

People who saw their brothers and sisters crossing the lines of humanity.

But they do not need to be only stories of dark times. Sometimes we let our grandparents leave without hearing once again, with adult ears, the stories of how they lived. What they feared and what they believed. Many of us do not know how our parents grew up, because we reduced our conversations to the necessary practicalities of life.

If they leave, and we waste our chance to hear from them about what better world they imagined, and if the world we live in today is very different from what they hoped for, we will be left with just one big hole that not even our own old age can mend.

©Sme

Great-grandfather often used to take me to the Lučenec cemetery. (source: Courtesy of Beata Balogová)

Great-grandfather often used to take me to the Lučenec cemetery. (source: Courtesy of Beata Balogová)