Russia had to invade Ukraine in order to protect Russian-speaking people from genocide at the hands of the Zelensky regime—so claims the Kremlin’s propaganda machine.

And nearly half of Slovaks believe it.

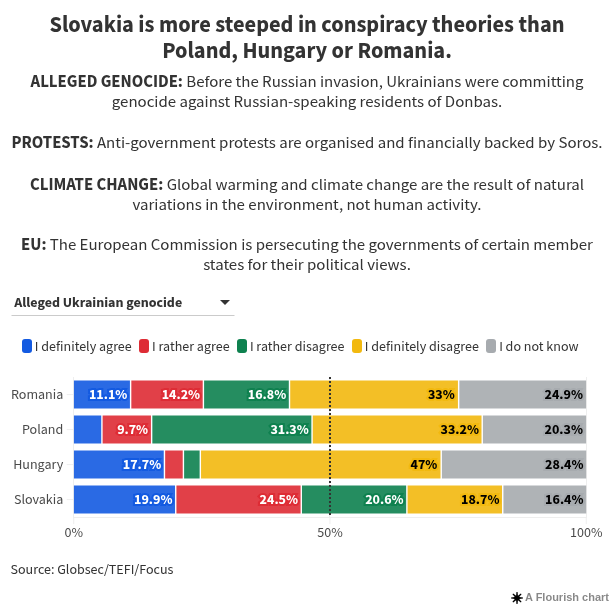

An exclusive poll conducted by the Focus agency and the Globsec think tank for the international project Eastern Frontier Initiative (TEFI) shows that 44 percent of Slovaks accept this disinformation narrative. Only 39 percent believe the opposite.

The same survey was carried out in Hungary, Poland, and Romania. Of the four, Slovakia came out as the most conspiracy-prone.

The military conflict in eastern Ukraine began in 2014, and since then international organisations such as the United Nations and the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe have monitored developments and human rights violations in the region. None have found any evidence of genocide or the targeted killing of ethnic Russians by Ukrainians.

That has not stopped Slovakia’s disinformation scene from regularly recycling the Kremlin’s genocidal claims. These assertions circulate not only on fringe websites and Telegram channels, but have also been repeated by coalition politicians—including Foreign Minister Juraj Blanár.

Last year, in a televised debate, Blanár claimed that between 2014 and 2021, Ukrainian forces had “murdered 14,000 people in Donbas”, citing a UN report. But the figure he referenced refers to all casualties in the conflict—Ukrainian, Russian, civilian and combatant—not to deliberate killings by Ukraine.

Soros and climate change

A large portion of the Slovak population continues to believe in the conspiracy theories and disinformation that circulate in the public sphere.

One of the most enduring is the claim that anti-government protests are organised and financially supported by billionaire financier and philanthropist George Soros. According to a recent survey, 44 percent of Slovaks agree with this theory, while the same proportion reject it. The so-called “Soros explanation” was first invoked in Slovakia by Robert Fico—then and now prime minister—following the 2018 murders of journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová.

Since the start of this year, as anti-government protests have continued, Fico has shifted focus to a different conspiracy theory: that the Georgian Legion is behind the protests and is attempting to organise a coup in Slovakia. Soros, notably, has not been mentioned in recent weeks.

Still, Fico has continued to push a narrative that the European Commission is punishing him for not holding the “right opinions”, particularly regarding Ukraine.

Nearly half of Slovaks believe that the European Commission persecutes certain governments for their political views. In contrast, 41 percent do not share this belief.

Another widespread conspiracy theory in Slovakia is the idea that global warming is not caused by human activity but is instead the result of natural environmental changes. Around 40 percent of people believe this; 54 percent disagree.

No current Slovak politician is actively promoting this view. However, some MEPs from the far-right Republika party and former SaS leader Richard Sulík have previously made statements casting doubt on the current fight against climate change.

While Slovakia ranks worst among the four surveyed countries in terms of belief in conspiracy theories about the war in Ukraine and European politics, it is in Poland where the highest proportion of people subscribe to the climate change denial narrative.

Hungary is doing better

Researcher Katarína Klingová from Globsec notes that public trust in conspiracy theories often mirrors the attitudes of political leaders.

“Not just in Slovakia, but in other countries too, we’re seeing a trend where people believe in problematic and polarising narratives simply because the politicians they voted for – and trust – told them so,” says Klingová.

Hungary, however, presents an intriguing case. Despite years of being portrayed as a national enemy by Viktor Orbán, only 26 percent of Hungarians believe that George Soros is organising and funding anti-government protests. This is striking given that Soros is originally from Hungary and has been a target of Orbán’s rhetoric far longer than Robert Fico has used him as a scapegoat in Slovakia.

“After years of hearing these claims, most Hungarians have grown immune to them and no longer believe them,” Klingová suggests.

The results from Hungary surprised even Martin Slosiarik, head of the Focus polling agency. When asked whether they agreed that the European Commission persecutes governments for their political views, only 30 percent of Hungarians said yes—14 percentage points fewer than in Slovakia.

“Given Orbán’s rhetoric, one would expect the level of agreement to be significantly higher,” Slosiarik noted.

Like Fico, Orbán is largely isolated within the EU and does not shy away from attacking Brussels in front of his voters. However, recent polls show his popularity waning. He has now been caught up by opposition leader Péter Magyar, who is openly pro-European.

Shift within Hlas

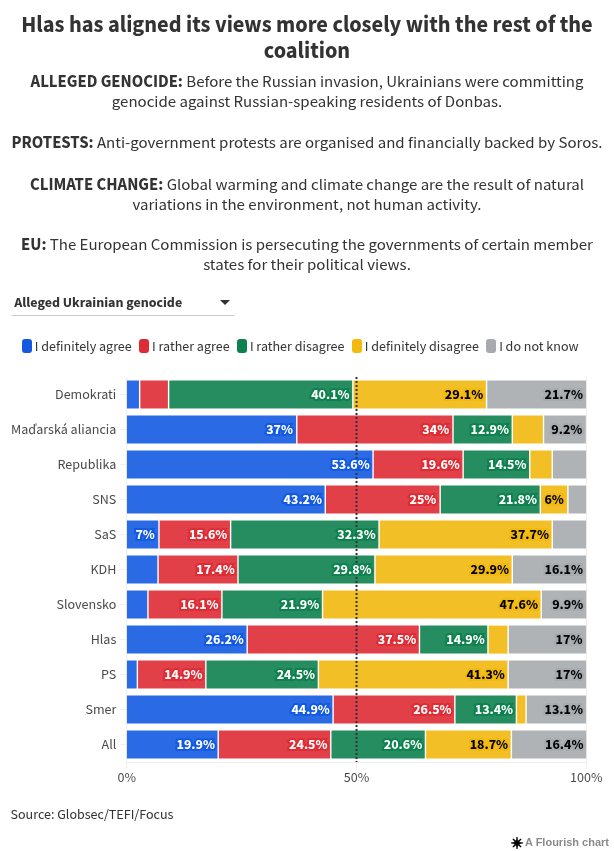

Agreement with individual statements explored in the survey is closely linked to whether respondents support the governing coalition or identify with the opposition.

The most conspiracy-prone respondents were voters of the governing coalition, the far-right Republika party, and the Hungarian Alliance.

In previous, similar surveys, differences in attitudes between Smer and Hlas voters were more pronounced. Hlas supporters typically fell somewhere between opposition voters and the rest of the coalition.

This time, however, the gap between Hlas voters and other coalition supporters has narrowed significantly—just a few percentage points. Hlas voters broadly agree with all the surveyed statements.

However, voter shifts have occurred since the election. Hlas appears to be gradually losing its more moderate supporters, with new voters tending to hold more radical views.

Opposition voters, as well as supporters of the extra-parliamentary Demokrati party, mostly disagree with the conspiracy-laden statements. “That said, even among opposition voters, agreement with several of the claims can be observed in around a fifth to a third of the electorate. So it would be wrong to dismiss these as isolated cases,” warned sociologist Slosiarik.

The Eastern Frontier Initiative

This article was written in the framework of The Eastern Frontier Initiative (TEFI) project. TEFI is a collaboration of independent publishers from Central and Eastern Europe, to foster common thinking and cooperation on European security issues in the region. The project aims to promote knowledge sharing in the European press and contribute to a more resilient European democracy.

Members of the consortium are 444 (Hungary), Gazeta Wyborcza (Poland), SME (Slovakia), PressOne (Romania), and Bellingcat (The Netherlands).The TEFI project is co-financed by the European Union.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.

Protesters during the anti-government rally "Slovakia is Europe" at Freedom Square in Banská Bystrica on 7 March 2025. (source: TASR - Ján Krošlák)

Protesters during the anti-government rally "Slovakia is Europe" at Freedom Square in Banská Bystrica on 7 March 2025. (source: TASR - Ján Krošlák)

(source: TEFI)

(source: TEFI)