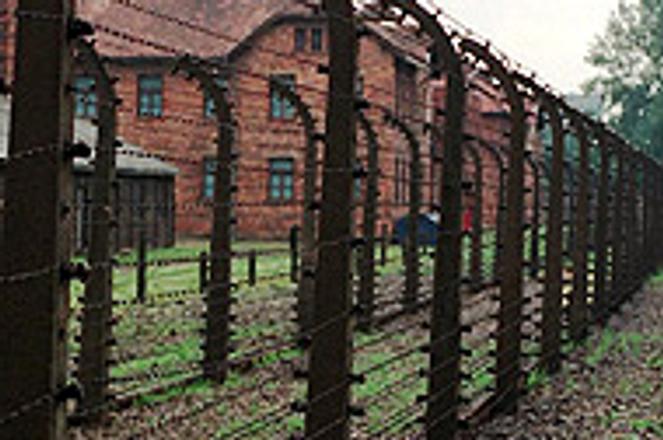

Some analysts are unhappy with the "superficial" response of Slovak politicians to the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitzphoto: TASR

THE WORLD looked back on one of its darkest periods in history this month - the Holocaust. January 27 marked the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz in Poland.

The UN General Assembly held a session January 24 to mark the liberation anniversary. The session was the first of its kind in the history of the UN General Assembly.

Six million European Jews (out of a population of nine million) were exterminated during the Holocaust. Millions of others - mostly Poles, Roma and Soviet prisoners - were taken to labour camps and perished in Eastern Europe.

The Auschwitz liberation commemoration celebrations throughout Europe are seen by many as the region's first collective reflection on the Holocaust and its actions during the 1940s.

Prime Minister Mikuláš Dzurinda expressed deep regret over the fate of those who lost their lives, homes, relatives and friends during World War II.

Dzurinda told the news wire TASR that Slovaks should remember the Holocaust as the absolute denial of freedom and life, and the liberation of Auschwitz as the ultimate destruction of a distorted ideology.

"I believe this sad memory will be a reminder to future generations," Dzurinda said.

He also said that Auschwitz and its liberation would remain one of the greatest symbols, even in the 21st century, of the fight to end crimes against humanity.

According to Dzurinda, Auschwitz has become synonymous with Nazi cruelty and violence, and the suffering and death of innocent people.

Slovak media outlets were critical of the country's politicians for their avoidance of mentioning Slovakia's role in the deportation of tens of thousands of Jews to death and labour camps in neighbouring countries.

According to the daily SME, Slovak politicians do not see a reason to apologize for the deportation of Jews from Slovakia, since the Slovak Parliament formally apologized for them in a declaration adopted in the early 1990s.

In 1939, based on a national census, 136,000 Jews lived in Slovakia. According to estimates, 105,000 Jewish men, women and children did not survive the Holocaust.

Slovakia's two strongest surviving Jewish communities are in Bratislava and Košice. Bratislava's Jewish community numbers is around 1,000 people, many of them Holocaust survivors.

The Slovak state during World War II ran active anti-Semitic campaigns and followed anti-Semitic policies. Slovakia sent its first transport of Jews (several hundred young women from Stropkov and neighbouring villages) to Auschwitz on March 25, 1942. Nearly all perished within the year.

Historians estimate that between 60,000 and 70,000 people were deported from Slovakia, destined for the various Nazi death and labour camps in the East.

Grigorij Mesežnikov, political analyst and the head of a Bratislava think tank, the Institute for Public Affairs, told The Slovak Spectator that the reactions of Slovakia's political elite to the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz were "insufficient, superficial and sterile."

According to Mesežnikov, the reactions "show that the Holocaust is still a rather sensitive topic in Slovakia".

"None of those who publicly reflected on the event tapped into the core of the horrors. This shows that Slovakia and its political elites still have an unresolved relationship with Slovakia's wartime state. Our government at the time was responsible for the liquidation of tens of thousands of Slovak citizens," the analyst said.

Apart from Jews, the Nazi regime also killed some 23,000 Roma. Klára Orgovánová, the cabinet's appointee representing Roma communities, said Slovakia is still "unable or unwilling to come to terms with its history, fix what can be fixed and mourn what cannot be fixed".

"Painful memories of victims - millions of Jews and a hundreds of thousands of Roma - will remain a memory that will become more painful if it is confronted with ignorance, rejection or even denial of past suffering," Orgovánová said in a public statement.

"This sad anniversary should motivate us to deepen our understanding ... This is the only way we can, in the future, reach the truth, and forgive," she said.

Representatives of the Milan Šimečka Foundation (NMŠ) also think that Slovakia has yet to come to terms with the Holocaust. It is currently pushing the issue into the peripheral vision of the public.

"If society is unable to perceive the evil of its past, it is questionable whether it will be able to recognize these tendencies today," NMŠ said in a statement published by the news wire SITA.