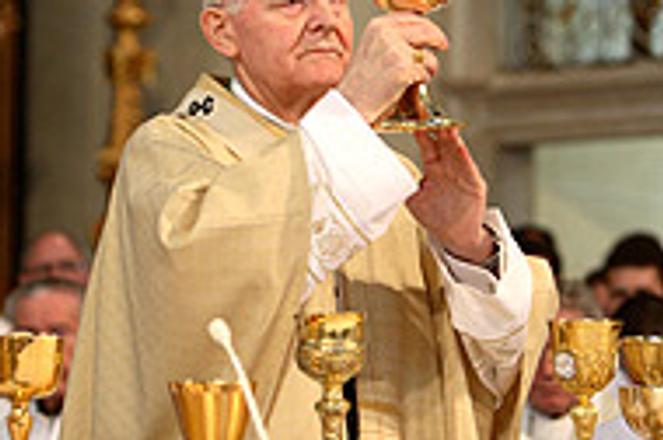

Archbishop Ján Sokol is back under public scrutiny after meeting with ÚPN head Ivan Petranský.

photo: TASR

A PUBLIC meeting between Ivan Petranský, the president of the board of the Nation's Memory Institute (ÚPN), and Archbishop Ján Sokol, who the ÚPN's archives have indicated cooperated with the communist secret police (ŠtB), has met with criticism since footage from it was shown by public broadcaster STV on May 12.

The ÚPN's job is to archive and publish documents and records kept by Slovakia's former totalitarian regimes, and not only those collected by the ŠtB but also those from the fascist regime of the first Slovak State, which was under the wing of Hitler's Germany. It aims to bring to light formerly hidden aspects of Slovakia's past and to bring the country to terms with its history.

According to STV's reporter, the aim of their meeting was to discuss an amendment to the Act on the ÚPN that would only permit it to publish documents that had been verified and proven to be true.

The meeting drew a strong response from some of the country's politicians and other observers of Slovakia's political scene.

Jozef Kovarčík, the deputy chairman of the ruling Movement for a Democratic Slovakia, was suspicious of Sokol's reasons for meeting with Petranský.

"I think that he is looking for a way to clean himself," said Kovarčík.

MP František Mikloško of the Christian Democrats also did not approve of the meeting.

"I do not think the Church should be present during the process of drafting such laws," said Mikloško.

However, when approached by The Slovak Spectator, Petranský denied that he met with Sokol to discuss amending the law on the ÚPN.

"It was a scientific conference entitled 'Communism Belongs Before an International Tribunal', organized by the Association of the Anti-communist Resistance," said Petranský. "I was invited there, just like dozens of other people were, including Archbishop Sokol, MP Rafael Rafaj [of the Slovak National Party (SNS)], and others. We met during the conference."

Petranský also said he did not think it was a problem that he had met with a Church official.

"Archbishop Sokol is the representative of the Bratislava-Trnava Archdiocese," he said. "He is the head of a religious province and so I saw no reason why I should not meet him. Due to my post, I often meet with representatives of religious, cultural and political life."

Before becoming the head of ÚPN, Petranský worked at the Archbishop's Office. His meeting with Sokol, his former boss, caused concerns that they might have been discussing a way to negate or destroy documents that show him to have cooperated with the ŠtB.

"They were looking for ways to declare that files connected to him are false," said Dušan Čaplovič, the deputy prime minister for human rights.

However, Petranský denied the possibility of a cover-up.

"We did not talk about destroying documents," he said. "Anything like that is out of question. Documents about Archbishop Sokol have already been declassified. They are widely known and it would not even be logical if we tried to destroy them now."

Petranský also ruled out the possibility that other, yet unpublished documents discrediting Sokol had been discussed along with possibilities of them "being lost in the future".

Some observers were concerned by the fact that Rafaj was present at the meeting because he is a member of the SNS, the party that nominated Petranský for the post of the head of the ÚPN.

However, Petranský denied that any political party could influence his work.

"Rafaj is a constitutional official," he said. "I meet with constitutional officials from many different parties, and Rafaj is just one of them. It is one thing to be closer to one political party than to another, but it is another thing to let it have an impact on the results of his or her work."

Petranský told The Slovak Spectator that he discussed several topics with Sokol, and the other conference attendees.

Changes to the Act on the ÚPN

Many political observers have spoken out against the possibility of changing the law concerning the ÚPN and requiring that files be 'verified' before being published.

Historian Dušan Kováč was one who disagreed with the proposed changes publicly.

"At the moment [the system] is based on the premise that the files are trustworthy and anyone who feels damaged by them can defend themselves and can try to prove their innocence," he said. "If it was the other way around, the institute may as well be abolished."

Čaplovič also criticized the idea of changing the law on the ÚPN.

"This idea could only occur inside heads that do not understand [the ÚPN] at all," he said. "The fundamental concept of the institute would be turned inside out. If the amendment passes the ÚPN will lose its purpose."

However, Petranský said critics have nothing to worry about.

"Concerning the amendment to the Act on the ÚPN, I do not support cutting the extent of information that is currently being published and declassified by the ÚPN," said Petranský. "On the contrary, I propose increasing the extent [of material published]. Most of all, it is important to declassify the files on the former members of the ŠtB - and at the moment that is practically impossible."