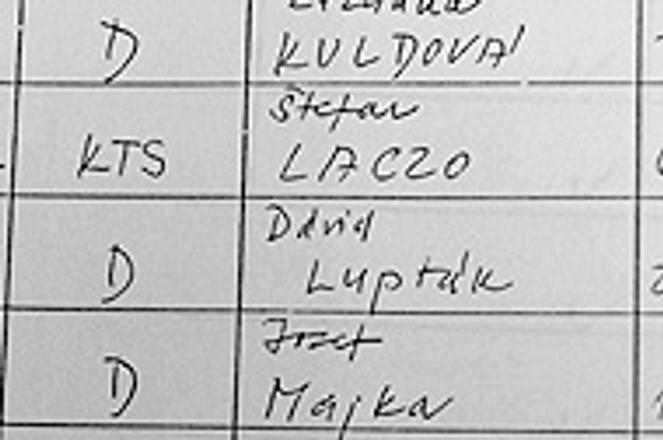

This file shows that Mečiar was a candidate for cooperation with the ŠtB.

photo: Jana Liptáková

THE NATION'S Memory Institute (ÚPN) has posted on its website a list of the files about collaborators with the Communist-era secret police (ŠtB) based on the country's Archives Act. The ÚPN also released the names of 2,927 former collaborators and agents on June 21 and made the archives accessible through the internet.

The file of Vladimír Mečiar, Slovakia's three-time prime minister, is not in the archives of the ÚPN. However, The Slovak Spectator found out that the ÚPN has the documentation on the investigation of the loss of Mečiar's files, and the files of other collaborators in the Trenčín district, from the ŠtB's former Trenčín headquarters, also known as Tisova Vila.

The loss of the files that could either prove or refute Mečiar's involvement with the ŠtB until 1986 has been attracting intense media attention.

Investigator Jozef Vaľo wrapped up the investigation and closed the file, numbered PV-007/05-1992, on October 30, 1992, saying that no crime had been committed at Tisova Vila and that no documents had been stolen from there. Vaľo said this despite several witnesses having had confirmed that they personally took the files from the headquarters and transported them to the Interior Ministry's Partizánska Street residence for Mečiar, who was serving as interior minister at the time.

Leonard Čimo, the former head of the inspection of the Interior Ministry, his driver Ján Rezník and Ján Mano, an employee of the Trenčín district police administration, have confirmed that Mečiar's files were stolen in late January 1990. Mano told investigators that he knew about "Čimo taking the documents, files, from Tisova Vila."

According to the investigation's records, Čimo told Czechoslovak police on February 3, 1992, that Mečiar, as interior minister, ordered him to find out whether the documents that the ŠtB had prepared on him were at Tisova Vila and to deliver all related documents to him. Čimo found the documents at Tisova Vila in a metal cupboard.

Mečiar's testimony in the investigation records.

photo: Jana Liptáková

"I did not search the materials in detail; I only counted the files in the folders," Čimo said. "There were eighteen. The folders suggested that these were files on secret collaborators of the ŠtB."

Čimo said that he and his driver drove the documents from Trenčín to Bratislava and handed them over to Mečiar at the Partizánska Street residence.

"I handed the documents over to Mečiar there," Čimo told the police. "I put them on the table and told him that there should be a record made of the documents being transferred. He responded that I shouldn't worry and that he would manage it."

Čimo's driver Rezník confirmed the story, though he did not remember the exact date, only that it happened in late January 1990. The driver said that he entered the villa after being asked to help and he saw some documents laying on the tables and chairs.

"Mr Čimo told me to take the files to the car," he said, adding that they drove straight to the Interior Ministry's residence and that he and Čimo took the files from the car into the ministry's residence.

"I think that it was some form of revenge on Čimo's part because I was determined to sack him," Mečiar said in 1992 when being questioned about the case, the investigation's documentation reports.

However, Mečiar did tell investigator Ctibor Košťál that some ŠtB files on Ján Budaj, a major proponent of the Velvet Revolution, Ladislav Košťa, a former federal Justice Minister and Ivan Čarnogurský, brother of the founder of the Christian Democratic Movement Ján Čarnogurský, were found at his residence but were later completely lost.

"Some time in July 1990, when I was already serving as prime minister, on arriving to work I found an envelope on my table that contained unverified photocopies of the files on Mr Budaj, Mr Košťa and Mr Ivan Čarnogurský," said Mečiar. "I personally destroyed the three files by tearing them up and burning them."

However, the investigation records that The Slovak Spectator inspected contain certain facts that pertain to Mečiar's links with the ŠtB.

Mano's testimonies from March 25, 1992, suggest that Mečiar worked as confidant of the regular police.

"Vladimír Mečiar's screening suggested that he cooperated with Peter Martiška," he said. Working as a confidant of the police did not exclude someone reporting to the secret police, said Mano, according to the investigation's records. An earlier reconstruction of the two-page file that was torn out of the ŠtB register proved that between 1985 and 1986, Mečiar was a candidate for becoming a collaborator with the ŠtB under the codename 'Doctor' and the registration number 31048.

Ján Patrnčiak, chief of the district office of the police between 1980 and 1989, told investigators that the ŠtB bureau in Trenčín did try to re-classify Mečiar from the category of candidate to that of agent.

"The essence of the situation Vladimír Mečiar should have been involved in was the protection of military objects in Nemšová," said Patrnčiak. Nemšová was a facility used by the Soviet army.

Patrnčiak also added that the ŠtB tried to use Mečiar's contact with the brother-in-law of Prague Spring figure Alexander Dubček, the investigation records report.

ŠtB agent Jozef Mikšík has confirmed that he was in charge of securing the military facility for the Soviet army in the Trenčín district and that he often visited the company Skloobal Nemšová, where Mečiar worked as a company lawyer. He also said that he and Mečiar were friends the documentation reports.

The Slovak Spectator contacted the press department of the Movement for a Democratic Slovakia, the party of which Mečiar is head, but received no response.

Anyone who wishes to can see the ÚPN's files can request a viewing through its website, www.upn.gov.sk.

The ÚPN will send a reply within two days and notify you when the documents are ready. The files on the web will be continuously updated.

The documents can only be read in one of the institute's study rooms. Viewing anything related to foreign intelligence service requires the approval of the chairman of the ÚPN board of directors.

The Nation's Memory Institute was established in 2002 to collect and archive files related to country's communist and fascist eras.