In January 2025, Meta founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg initiated the most significant shift in the company's philosophy, marking its biggest transformation in recent years. He expressed dissatisfaction with the governments of EU member states, threw the company's fact-checkers overboard – labelling them "censors" – and decided to adopt Elon Musk's content moderation model, which relies on ordinary users rather than professionals to flag false information.

While Meta's platforms – Facebook, Instagram and Threads – remain unchanged on the surface, fundamental transformations are taking place behind the scenes. These changes will affect the type of content viewed by hundreds of millions of American users. Already, European users are beginning to experience some of these effects, although they are currently protected by EU regulations, namely the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA).

The ultimate goal of Mark Zuckerberg – alongside Elon Musk and others – is to erase the distinctions between the American and European markets, and thus reinstate an era of self-regulation and technological anarchy.

Understanding why

Mark Zuckerberg has always been a controversial figure. His success story is that of an unassuming young man who dropped out of university to launch what became a multi-billion-dollar company. However, it is also the story of a problematic student who sought to publicly rate the appearances of his female classmates online, and whose declarations of good intent were not always easy to trust.

Zuckerberg spent years portraying himself as someone genuinely committed to the well-being of his users. This was evident as late as early 2021, when Facebook (the parent company would not be renamed Meta until months later) decided to reduce the volume of political content on its flagship platform. The company said it was prioritizing more valuable and meaningful content, accepting the trade-off that users might spend less time on the platform as a result. According to internal company statistics, within a year, users were exposed to up to 50 percent less content related to politics and social issues. Zuckerberg's decision was unexpected, and many doubted him, but the initiative persuaded some that, despite past scepticism, he was acting in good faith.

In January 2025, Zuckerberg announced a dramatic reversal. Meta's platforms were undergoing another transformation, but so was Zuckerberg himself. He is no longer a reserved figure in a grey T-shirt. He now shares more of his private life, experiments with his style, prominently wears a gold chain, and trains in mixed martial arts (MMA). His outward image has transformed, but more importantly, so has his professed mindset.

In the months leading up to Donald Trump's election, Zuckerberg cautiously and unexpectedly began discussing what he calls "censorship". Later, he officially attended Trump's inauguration, and the shift culminated in his January announcement – a turning point that dispelled any remaining doubts about his true intentions. It was not merely about the proposed changes but also about the sharp and misleading rhetoric that have accompanied them, in which he accused journalists and fact-checkers of "censorship".

Zuckerberg declared that users would enjoy greater freedom of expression and indirectly suggested that he hoped European regulators would embrace the same approach.

Dangerous reach

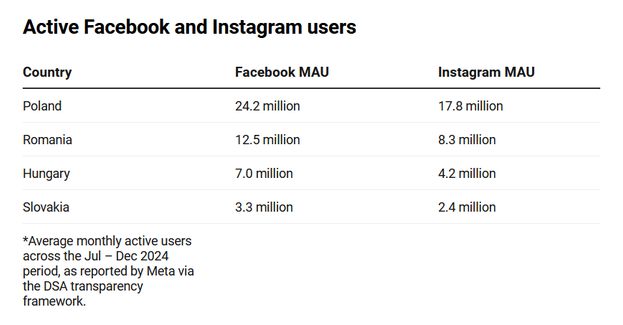

Facebook alone has more than three billion monthly active users (MAU) worldwide – individuals who log into the platform at least once every 30 days. In most European countries, it remains the largest social network. While Threads, as a relatively young platform, is still marginal, Instagram, alongside Facebook, ranks among the most widely used social media services. This also holds for TEFI countries:

In all listed countries, more than half of the total population actively uses at least one of Meta's platforms. Changes in internal policies regarding content rules and moderation, therefore, have the potential to influence a huge number of people.

The impact of these changes could affect public awareness (especially among voters) and contribute to societal polarisation. One of the primary risks is the spread of harmful content, including – but not limited to – misinformation.

A step backwards

In January 2025, Zuckerberg announced three major changes. While they were presented as efforts to enhance freedom of expression and prevent past errors that – he alleged – have led to this freedom being unjustly restricted, each of these changes comes with clearly foreseeable negative consequences.

Change of rules: Meta has decided to simplify its rulebook known as the Community Guidelines, which were previously extensive and complex. However, this simplification has created more room for negative content. In particular, borderline content that, under previous guidelines, would have been classified as hateful or offensive is now permitted. These changes primarily affect women and marginalised groups, providing greater space for misogyny and verbal attacks against the LGBT+ community.

Based on the new hateful conduct policy, users are now allowed to refer to women as "household objects or property" or to transgender or non-binary people as "it" – expressions that were previously prohibited. By contrast, it is now permissible to raise "allegations of mental illness or abnormality when based on gender or sexual orientation, given political and religious discourse about transgenderism and homosexuality."

End of fact-checking: Meta launched its internal fact-checking programme in 2016. During the following years, it proudly promoted its network of fact-checkers who verified content accuracy across dozens of languages and more than a hundred countries. Whenever Meta needed to demonstrate to regulators that it was combating misinformation, it played the fact-checking card. No longer.

Mark Zuckerberg unceremoniously abandoned independent fact-checkers – external, certified professionals – and, beyond that, falsely accused them of censorship. Yet fact-checkers never had the authority to remove content; that power lies solely with Meta's internal moderators, who, ironically, do not intervene against misinformation. By conflating these two distinct entities, Zuckerberg effectively turned on the very individuals who had indirectly helped shield him from regulatory pressure for years.

The termination of the fact-checking programme in the United States will create space for the spread of falsehoods. For Meta, this means cost savings and fewer obligations to maintain partnerships with relevant organisations.

Moreover, in the long term, it is clear that Meta's ideal scenario involves the global elimination of fact-checking, including in the European market. For now, this is prevented by the Digital Services Act (DSA) as, without fact-checkers, Meta could struggle to convince authorities that it is taking all necessary measures to prevent the misuse of its digital platforms.

Replacement of experts: Meta declares that it is not completely abandoning content verification but is merely changing its approach, adopting the model used by Elon Musk's platform, X (formerly Twitter). This involves the Community Notes feature, where ordinary users review posts in their free time.

The system attempts to determine whether individuals submitting feedback on problematic content come from different ideological backgrounds. If a sufficient number of users from opposing viewpoints agree on a correction, a notification with the note appears beneath the relevant post.

While this approach theoretically increases fact-checking capacity, in practice, it has significant shortcomings, as observed in recent years on X. One of the known flaws is that the majority of verified content tends to be less critical. In contrast, highly polarising topics, such as politics, receive minimal scrutiny, as reaching consensus among users with opposing views is significantly more challenging.

This marks a fundamental difference from professional fact-checkers, who strive to maintain neutrality in their content assessments.

Reaching Europe

The consequences for the European market are already becoming visible, because Zuckerberg has also reversed the decision to limit the reach of political content, ordering its return to an "organic" level. Allegedly, this move is a response to user preferences, as they reportedly now request more political content, despite Meta previously claiming that, just a few years ago, users had demanded the very opposite.

"The change you are referring to is indeed related to Mark's announcement and we can confirm that globally (not just in USA) we are taking more personalised approach to political content, so that people who want to see more of it in their feeds can," Meta confirmed in February in a statement for the SME daily.

At that time, Facebook users themselves began reporting the change, including those who had previously not engaged with political content on the platform and whose behaviour gave Meta's algorithm no reason to assume they would be interested in it.

Many users even reported seeing content from far-right political parties – content that starkly contrasted with their personal and political beliefs.

(Far) Right opportunity

More space for political content in the news feed opens room for competition among political parties. However, whether this competition will be fair remains uncertain.

It is well known that Meta's social media algorithms favour polarising content and negative emotion. This tendency is particularly exploited – or even abused – by populist and far-right parties. Since their political communication is often based on personal attacks and negativity, which generate high engagement rates, the algorithm amplifies the spread of such content to a greater extent.

Meanwhile, factual and truthful posts are generally less engaging. As a result, political parties striving for constructive or positive communication typically face a competitive disadvantage.

Tough decisions

It is worth noting that political speech has long enjoyed a higher degree of protection by Meta. Posts made by politicians, political candidates or elected officials are exempt from fact-checking – in simple terms, they are allowed to spread misinformation.

Despite this, Meta has, on rare occasions, intervened. One such case was that of Slovak politician Ľuboš Blaha, who at the time Meta acted was an opposition member of parliament. From 2018 he had built a Facebook fan page with 175,000 followers and became one of the most influential political figures on the platform, largely due to his dissemination of misinformation, including content related to Covid-19.

Although somewhat late to act, in the summer of 2022 Meta decided to remove Blaha from Facebook. The primary reasons cited were his hate speech and dangerous medical misinformation. However, much like in the case of Donald Trump – who was banned following the attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021 – Blaha, who is now a member of the European Parliament, was eventually allowed to return to the platform.

This reinstatement took place recently, in May 2025, without a clear explanation. While the company had previously provided journalists with a briefing and adequately communicated its decision regarding his removal, it failed to sufficiently justify the latest action, which appears to align with its new policy direction.

"After reviewing our previous enforcement decisions, we've restored MEP Blaha's access to Facebook," Meta stated vaguely, refusing to provide any further clarification to journalists.

Blaha is not the only European politician Meta has penalised. However, while previous removals were carried out cautiously, often delayed or influenced by external pressure, the reversal of such decisions might be happening more easily and swiftly. It will be important to monitor whether this develops into a broader negative trend in the European market.

It may get worse

One of the biggest concerns regarding the reversal of previous decisions and policies relates to Meta's internal blacklist – the Dangerous Organizations and Individuals (DOI) list – which includes various terrorist organisations as well as individuals spreading extremist or hateful content.

Despite being listed, Hungarian far-right politician László Toroczkai returned to the platform in late 2024, after a dispute with the company. However, he was blocked again just a few days later. His case bears similarities to that of Ľuboš Blaha, who also claims Meta allowed his reinstatement only after he threatened legal action.

Some users fear that under its new policy, Meta may become more susceptible to pressure, particularly in borderline cases where bans are challenged in court. However, the company has officially stated that no changes have been made in this regard.

"There has been no change to Meta's DOI policies. Of note, Joel Kaplan (Chief Global Affairs Officer at Meta) explicitly said in the blog that we will be focusing our automated enforcement on things like terrorism because everyone agrees no one wants that on the platform," the company assures.

What to look for

While it is evident that the shift in Meta's corporate philosophy is linked to the return of Donald Trump and the prospect of deregulating major tech corporations, the extent to which companies like Meta will succeed outside their home market, where the US administration has no direct influence, remains uncertain.

In January, it appeared that Donald Trump would push to reduce bureaucratic burdens for American companies outside the US, possibly as part of a trade war. However, while that conflict is indeed ongoing, technology firms have yet to play a significant role in it.

On the contrary, despite concerns that the European Commission might come under pressure to ease its oversight of large digital platforms, it has so far remained firm, continuing to impose hundreds of millions of euros in fines on US companies for violations of the DSA and DMA.

At present, these fines serve as the primary deterrent mechanism by which the European Union can safeguard its market from influence on European users – an influence that shapes their decisions both in the digital sphere and in the real world. From the perspective of democracy and electoral integrity, ensuring this remains the case will be crucial.

The Eastern Frontier Initiative

This article was written in the framework of The Eastern Frontier Initiative (TEFI) project. TEFI is a collaboration of independent publishers from Central and Eastern Europe, to foster common thinking and cooperation on European security issues in the region. The project aims to promote knowledge sharing in the European press and contribute to a more resilient European democracy.

Members of the consortium are 444 (Hungary), Gazeta Wyborcza (Poland), SME (Slovakia), PressOne (Romania), and Bellingcat (The Netherlands).The TEFI project is co-financed by the European Union.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.

Facebook founder, Mark Zuckerberg (source: AP/TASR)

Facebook founder, Mark Zuckerberg (source: AP/TASR)

(source: TEFI)

(source: TEFI)

(source: TEFI)

(source: TEFI)