HELENA looks rather amused by the idea of granting an interview. She tries to arrange her hair a bit and bursts into a laugh when I tell her that I work for radio, not TV.

“Don’t ask me difficult questions, please!” she says, gently pushing aside one of her teammates poking fun at her newly found celebrity status.

“I have been taking care of children in school so this is how I get to know their parents too,” Helena explains. “I am here to make sure that they go with their children to regular check ups at the doctor, get them vaccinated and follow the treatment they were prescribed. I take care of adults too.”

Helena takes a few steps back, puts her palm near her ear pretending she receives a phone call from a hospital, apparently a nurse asking her to go to family X to tell them that they should come to pick up a family member. She hangs up the imaginary phone.

“Everybody here knows me and I know that if I shout the name of that family they would not bother to reply but if I go and knock on their door they have to deal with me,” she says. “I must admit that sometimes I have to threaten them with calling the police because they find all sorts of excuses. I know that life is very harsh for them but I have to be serious about this because it is my responsibility to be....ahmmm.... this....ahmmm...” I suggest the word mediator and she quickly repeats it after me, her voice full of pride.

“They know that when they need help, if I call the ambulance, saying who I am and explaining what the problem is with my bit of expert knowledge, the ambulance will come in five minutes, whereas if they themselves call, it comes much later.”

Helena would be happy to demonstrate how to deal with an infected wound on a child’s arm or check my pulse. Then she switches to the topic of hepatitis, which is a serious issue in the communities that she is in charge of and which is “a disease of poverty that can be prevented through vaccination,”she expertly adds.

Although in her late 40s, this woman has the enthusiasm of a child willing to show the latest trick she learnt. She graciously surfs through medicine, social protection, labour market policies and even a bit of finance when she gets angry about lending policies that discriminate against people from her district.

“I want to do this job as long as I can. I like it. My family supports me, especially my children, they are proud of me. I want to train other people in my community too. But I will tell them from the very beginning that it’s not an easy job at all.”

Once she had to go to a family and bring them the news that their child had died in hospital.

“It was hard,” she says. “I felt like a doctor who lost a patient.”

Helena does not have any academic title before or after her name. No Mgr, no Ing, no MUDr no MPH (Master of Public Health). She is a Roma healthcare assistant. When I met her in 2013 she was living in a poor segregated district of Košice, Slovakia’s second largest city.

I thought of her a few days ago when going to pick up my drug prescription from the shiny brand new building of a hospital in downtown Bratislava. A nurse barked at me “Neviete čítať?” (Can’t you read?) and slammed the door in my face. My sin? I accidentally stood in front of the wrong office.

I think of Helena when I attend press conferences with at least an MPH title holder in the panel who keeps on repeating “To sa nedá” (It cannot be done).

I think of Helena when some neurotic pharmacist holding my insurance card issued by the second largest health insurance company in Slovakia in her hand keeps on asking me whether I have health insurance and when I point to the card she replies: “But you are a foreigner.”

Helena belongs to my “other Slovakia” – the open, enthusiastic, and daring one.

Anca Dragu is a journalist withRadio Slovakia International, which is available in Bratislava in English on 98.9 FM at 6:30pm and 8:30pm and atwww.rsi.sk. The opinions expressed in this blog are her own.

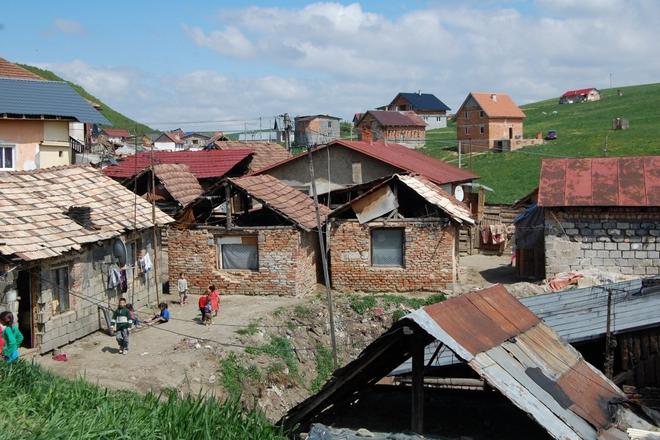

Roma settlement in Markušovce (source: Ingrid Ďurinová)

Roma settlement in Markušovce (source: Ingrid Ďurinová)