Labour productivity in Slovakia is growing, fuelled by investments and job cuts, with the latter also curbing wage growth. In 2013 productivity growth is forecast to continue outpacing wage growth. But given the current economic conditions, experts say, this improvement in productivity is not so much an advantage as an absolute necessity in order to survive amidst heightened competition.

“Over the long term, the most important factor influencing growth in labour productivity is an inflow of new foreign direct investments and associated new technologies, which enable Slovak labour to be employed in more efficient means of production,” Vladimír Vaňo, chief economist at Sberbank Slovensko, told The Slovak Spectator. “Expansion of industries with higher added value, including automotive, electronics, production of computers, electrical and optical equipment, also contributed to the robust productivity growth during the decade preceding the global recession of 2009.”

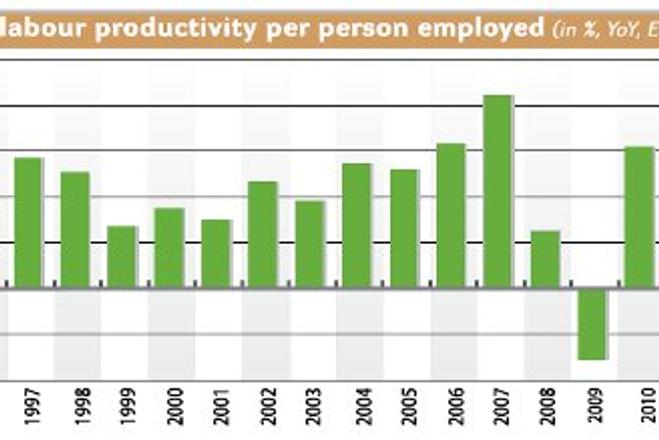

Real labour productivity per person employed in Slovakia increased on average by 4.8 percent annually during 1995-2008 period, Vaňo said, citing Eurostat statistics. During the recession in 2009, real labour productivity in Slovakia declined by 3 percent year-on-year. The following year it rebounded, rising by 6.0 percent year-on-year, as a result of a recovery in export-driven economic growth combined with payroll downsizing during and shortly after the recession. However, average real labour productivity growth over the past two years has been only 1.8 percent per annum.

Over the past few years, the development of real labour productivity has been affected by overall macroeconomic development: when the global recession hit, and real GDP fell by 4.7 percent in 2009, this also hit productivity, which declined by 3.0 percent; this, in turn, triggered layoffs, which increased official unemployment by almost 5 percentage points.

“Paradoxically, this payroll downsizing contributed to an at-first-glance impressive rebound in real labour productivity in 2010: as economic growth driven by exports to the eurozone recovered, the economy was producing higher output with less employment,” said Vaňo. “The slight increase in productivity of 1.8 percent on average during the past two years helps to explain why, while we have seen stagnation in the labour market and the unemployment rate, the Slovak economy has recorded some of its strongest growth for the past few years. In order to remain competitive, Slovak producers have little other option than to continue pushing for higher productivity and hence also better competitiveness.”

Slovakia’s real productivity growth – especially over the past seven years when it averaged 3.3 percent – compares relatively favourably with other central European countries, according to Vaňo. Real productivity growth in Poland was 2.3 percent on average over the same period, 1.6 percent in the Czech Republic and only 0.1 percent in Hungary.

Vaňo said that it comes as little surprise that Slovakia’s real productivity growth has exceeded that of the more developed eurozone members.

“An emerging economy growing from a lower starting base should be able to record not only faster potential real GDP growth, in order to catch up with the developed economies, but likewise, emerging economies should also be able to eke out stronger real productivity growth, in order for living standards (and incomes) to approach the levels of the developed countries,” said Vaňo. “The only sustainable way to increase household incomes is to create conditions in which the annual real growth of wages does not exceed the pace of real productivity increases.”

Vaňo added that the opposite, i.e. average wage growth that outstrips productivity growth, would be detrimental to the competitiveness of companies, industries and the country as a whole, as has been seen in Hungary over the past decade.

The average gross nominal monthly wage increased in Slovakia by 2 percent year-on-year to €784 during the third quarter of 2012, Ľubomír Koršňák, an analyst with UniCredit Bank Slovakia, wrote in a bank memo. This represented the seventh consecutive fall in monthly real wages, down by 1.6 percent.

“Also during the third quarter nominal wage growth lagged behind labour productivity growth, which was 3.8 percent,” wrote Koršňák. “Such a development should also persist during the ensuing quarters.”

Koršňák expects that wage growth will continue to be restrained by the surplus of unemployed labour on the market, as well as by public-sector wage signals.

“The growth of nominal wages should also lag behind the growth in labour productivity during the following quarters,” wrote Koršňák. “However, decelerating inflation should contribute in 2013 to a moderation in the decline of real wages.”

According to Vaňo, sufficient growth in real labour productivity is a necessary precondition for, but not a guarantee of, commensurate real income growth.

“Keep in mind that one way of increasing labour productivity is to produce the same amount of output with less labour, i.e. by laying off staff,” said Vaňo. “The development of average wages, especially over the past five years, is driven by forces of supply and demand in the labour market. With registered unemployment close to the highest levels since April 2004, the labour market is a buyer’s market, i.e. employers have the upper hand when it comes to annual flat wage hikes.”

Vaňo warns that during the recent period of global economic turbulence in particular, improvement in productivity is not merely an option but an absolute necessity in order to survive in conditions of heightened competition and meagre demand. The development of labour productivity and wages will depend on actual economic growth.

“It is very likely that Slovakia will continue bleeding jobs, i.e. that employment will decline, in 2013,” said Vaňo. “Hence, if we manage to avoid recession, the combination of a slight growth in economic activity coupled with a decline in employment might actually generate positive growth in real labour productivity. However, these would not be the kind of macroeconomic statistics to be cheered, as they would be partly the result of a bloodbath in the labour market.”

For more information about the Slovak labour market, HR sector and career issues in Slovakia please see our Career & Employment Guide.

Real labour productivity per person employed

Real labour productivity per person employed