AFTER A slight downtick last year, the future of Slovakia’s cinema production again looks promising. The first major film event of 2011, the recent Berlinale, brought into the spotlight several young talents who might become the leaders of what the Berliner Zeitung called “a small Czech-Slovak New Wave”.

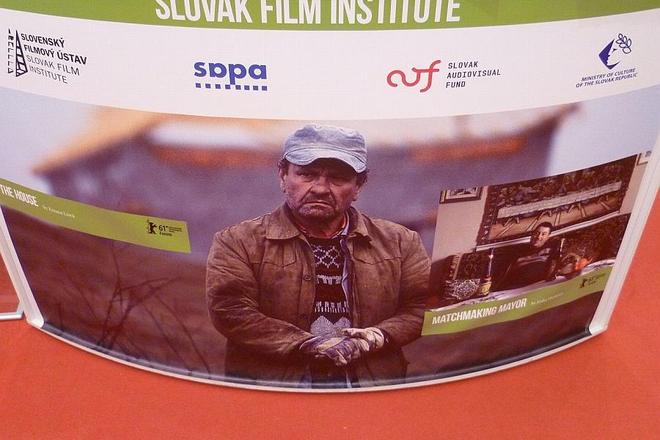

“It is not commonplace for us to have as many as two new movies with Slovak participation at the Berlinale,” said Alexandra Strelková from the Slovak Film Institute, referring to Slovak director Zuzana Liová’s feature The House (Dom) and Czech director Erika Hníková’s documentary Matchmaking Mayor (Nesvatbov), both co-produced by Slovakia and the Czech Republic. “Our Central European Cinema stand at the European Film Market, which we traditionally share with our colleagues from the Czech Republic and Slovenia, was this year really swarming with film professionals who inquired both about the two movies screened and about the current state of Slovak cinema,” she told The Slovak Spectator. However, the buzz and excitement soon spread outside the market, too.

Matchmaking Mayor, a story about a mayor’s idea to hold a matchmaking dance for his village’s singles, was praised by Variety for its “forthright, amusing approach to topical subject matter” and it even received Der Tagesspiegel Readers’ Jury Award. Marek Urban, the Slovak co-producer of the movie, explained that the early idea behind Hníková’s third documentary was very different from its final version.

“Originally, the movie was called “Weddings According to the Mayor” and it was supposed to be a film about a mayor who has the recipe for the present-day phenomenon of singles,” he stated. “But as usually happens with documentaries, reality is the best screenwriter and our “Wedding Village” became “No Wedding Village” [in Czech] despite all the mayor’s efforts.” As Hníková explained in a press release, what makes the film unique is exactly this mayor who governs the eastern Slovak village of Zemplínske Hámre. She added that people who have not started a family by the age of 35 can, of course, be found elsewhere in Europe, but Matchmaking Mayor is also about different kinds of solitude, about the village milieu where traditional values no longer apply, and about the mayor’s Sisyphean struggle.

The House was equally successful at attracting the attention of the visitors to the Berlinale. According to the Sme daily, the premiere of the movie was followed by enthusiastic applause and cheers as well as by a long discussion with director Zuzana Liová and actors Miroslav Krobot, Táňa Medřická and Judit Bartos.

“I had only finished the movie two weeks before so I was very tired and did not have any distance from my work,” Liová told The Slovak Spectator. “But when I saw the reaction of the audience, very positive and emotional, energy came back to me all at once. The journey from the script to a finished film had been a tough one, but seeing some people with tears in their eyes after the screening made me feel it was worth it.”

The House tells the story of a teenage girl who wants to escape her remote, sleepy hometown to work as a babysitter in London. However, her father has other plans and is building her a house next door. He is all the more obstinate as he had previously started constructing, but failed to complete, another house for his elder daughter who had managed to flee the family nest.

Variety called the movie “perfectly proportioned”, regarding Liová as the equal of her regional contemporaries, while The Hollywood Reporter recommended The House “for lovers of Ken Loach-style realistic dramas built on naturalistic performances, sans the politics”.

Liová, who has received many international awards for her previous works said she chiefly draws inspiration from people around her. “Through my film I attempted to show the difficulty of understanding each other and asking for what we actually want, be it a mere hug,” she remarked. “The two half-finished houses, unwished-for yet sincerely offered, symbolise my characters’ inability to open themselves before one another.”

Michal Kollár, The House’s Slovak co-producer, said that the film, which was shot over a period of two years, was very dear to him in many respects. “The House is unusually genuine and simple,” he said. “It evokes the deepest emotions and forces us to reconsider our values. Within 90 minutes, Zuzana achieves what a soap opera does not achieve within a hundred episodes.”

And it seems the Berlinale is only the first swallow in the possible upturn of Slovak cinema: at least 15 feature and documentary movies produced and co-produced in Slovakia are expected to be released in 2011. These include, for example, Apricot Island by Peter Bebjak, Cherry Boy (Čerešňový chlapec) by Stanislav Párnický, and Gypsy by Martin Šulík. However, compared to the neighbouring countries, the situation is not yet satisfactory, filmmakers agree. Kollár said that for Slovak movies to become more numerous the distribution system of state film subsidies should be improved, which in turn cannot be achieved without more public support. “Nobody questions the amount of money received by tennis or ice hockey players for their individual training, yet these sums often exceed the yearly budget allocated to the overall domestic film production,” he told The Slovak Spectator. “I believe the public should be informed about the necessity of increasing this kind of support.”

A billboard advertising Slovak films at this year's Berlinale. (source: Courtesy of Fog'n'Desire Films)

A billboard advertising Slovak films at this year's Berlinale. (source: Courtesy of Fog'n'Desire Films)