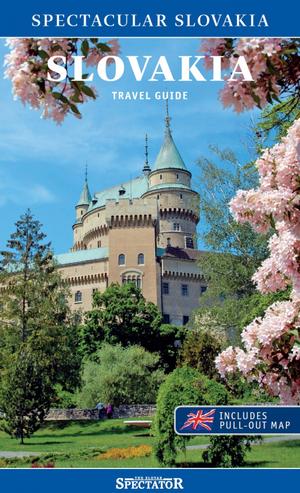

This is an article from our archive of travel guides, Spectacular Slovakia. We decided to publish this gem for our readers, as it is great example of how the face of Slovakia is changing. The country‘s pro-european orientation is now clear. The last decade in Slovakia was represented by solid economical growth and Slovak-Hungarian tensions are no longer a point of dicusision for top politicians. For up-to-date information and feature stories, take a look at the latest edition of our Slovak Travel Guide.

www.spectacularslovakia.sk

www.spectacularslovakia.sk

While Slovakia as a country may seem uncertain about its future orientation - west to the European Union or a return eastwards? - Komárno knows exactly what it wants. And contrary to what nationalist politicians believe, it does not want a Greater Hungary.

Komárno simply wants to be a part of Europe.

The city’s Euro-attitude is embodied by its newest attraction: Europe Place. The recently constructed square in the city centre consists of buildings designed in architectural styles distinct to different European countries and beyond. The Hungarian building is found next to the Slovak, the French next to the Russian, the Austrian next to the Spanish. Everyone is included here, from Greenland to Turkey, the Vatican to Transylvania.

The square was opened in December 2000 and covers 6,500 square metres of land. There is an underground car park, and ‘Euro Alley’, a shopping complex below the square. The centrepiece is the Millennium Fountain. On the whole, the square is dazzling, a dizzying swirl of colour and fine detail.

Ironically, this project of unity is found in an area that has long been divisive for Slovaks. Populists love to paint the predominantly ethnic-Hungarian residents as anti-Slovak, saying that they have the interests of Hungary dearer to their hearts than those of Slovakia. Who can ever forget an allegedly drunk Ján Slota, the former head of the Slovak National Party, making his impassioned call in 1998 for Slovaks to man their tanks and storm Budapest?

Tension

Controversy also arose in 2001 when the ethnic-Hungarian party, SMK, demanded the formation of a ‘Komárno County’ during public administration reform. The district’s voters would have been predominantly Hungarian. Party leaders said it would allow locals a louder voice in regional governments; nearly every other Slovak politician was opposed, saying the creation of such a county would be tantamount to dividing the country along racial lines.

The most recent row originated in Budapest. In summer 2001, Hungarian legislators passed a Status Law that would give ethnic Hungarians living in neighbouring countries special privileges, including subsidies for education at Hungarian schools in Slovakia. Bratislava charged the Hungarians with imposing a foreign law on a sovereign state, a law that would no less discriminate against ethnic Slovaks. Budapest responded by hinting that they would block Slovakia’s Nato entry.

Considering all the above, one almost expects to find a city on the edge, where ethnic Slovaks and Hungarians are constantly at each other’s throats (the racial division is approximately 65% Hungarian, 35% Slovak). This of course is not the case. Komárno is peaceful and friendly - and surprisingly indifferent to disparaging comments made up north about southern Slovakia.

Local economy

“People like Slota have blinders on,” said Cszaba (pronounced Cha-ba), an ethnic-Hungarian I met at Europe Place. “When they say the things they say, what can we do but shrug our shoulders? We just ignore it down here. Every country has its nationalists. Slovakia is no different.

“What they don’t seem to realise is that it is all about money. If the Slovak economy were better, Hungarians in Slovakia would not be a problem. But nobody has money. Unemployment is everywhere. So they pick on us. They say we’re trying to undermine the state, that we’re not loyal, that we want to be a part of a Greater Hungary. If we all had some more money, though, this would not be an issue.”

Unemployment has been particularly devastating in Komárno. Because it sits at the confluence of the Danube and the Váh, Slovakia’s longest river, the economy has been based around shipbuilder Slovenské Lodenice Komárno (Slovak Shipyards Komárno). But mismanagement in the late 1990s forced the firm to cut its workforce, from 5,500 before the revolution to about 800 today. The effects are felt all around town: Unemployment is at about 25%, and in the Euro Alley shopping complex only a quarter of the retail space has been opened as traders wonder who they would sell to.

The problems here are no different from in the rest of the country, says Cszaba, who is tired of speaking about these issues. “How many times do we have to say we don’t want to go back to Hungary? These nationalists up north are pointing their fingers at Hungarians and thumping their chests for Slovaks, but what we should all be doing is working together for the EU. I prefer politicians like [Foreign Minister] Eduard Kukan. He looks around and says, ‘Okay, how can we all - Hungarian, Slovak, whoever - work together to improve our lives and our country. I like Kukan. But I don’t like politicians with tunnel-vision.”

Unexpected

Komárno may surprise first-time visitors. It is not anti-Slovak, the people are not pining for a Hungarian reunion. And contrary to popular ethnic-Slovak belief, everyone here speaks Slovak. The language of choice may be Hungarian, but people addressed in Slovak switch over with neither hesitation nor irritation. In public places, visitors are greeted with the bilingual “Jó napot. Dobrý deň.” The Irish Pub on Europe Place even has a waiter who throws in a ‘Good day’. (He speaks German, too.)

Our Spectacular Slovakia travel guides are available in our online shop.

“Everyone has to learn the national language,” an elderly man told me in Slovak. “Sure, we mainly speak Hungarian here, but if I go 100 kilometres north, nobody does. I hate that term ‘Na Slovensku, po slovensky’ (In Slovakia, speak Slovak). But - without the silly nationalist rhetoric behind it - it is true... to a certain extent.”

Euro Place. Multilingual and open-minded people. A firm western orientation. Could it be that Komárno - so often the target of national ire - is more prepared for the European Union than is the rest of Slovakia?

Komárno history

Komárno is one of the oldest towns in Slovakia. It has been settled continuously since the early Bronze Age.

The Romans built a military camp here in the 2nd century, but were pushed out by nomadic Avar tribes in the 4th century. Hungarian tribes took over in the 10th century and built the town’s first castle. King Belo IV gave Komárno municipal rights in 1265.The castle became the focus of the Hungarian Kingdom’s anti-Turk defence system. Constructed between 1546 and 1557, the remains of the Komárno defence system are today the largest bastion fortification in central Europe. It defended the city well: the Turks never conquered the city, although they did manage to burn it to the ground in 1529 and 1594. The fortification system can today be traced on foot in little over an hour. The sixth bastion, north-east of the train station, has a museum, night club and restaurant. It was reconstructed in 1991.

Komárno was granted the status of a free royal borough by Empress Maria Theresa in 1745. At the time, Komárno was the fifth largest city in the Hungarian Kingdom with 10,000 inhabitants. The economy was based on trade and crafts, ship-building, and a haulage system whereby boats were pulled upstream by teams of horses on the river bank. Komárno supplied the Royal Court with fish from the 16th century.

Natural disasters were frequent: an earthquake damaged the largest structures in 1763; a large chunk of the town and 19 boats were destroyed in a furious storm on September 17, 1848; major floods wreaked havoc in 1800, 1876 and 1880; and plague outbreaks were also common.Komárno became part of Czechoslovakia in 1920 when the Treaty of Trianon divided the city in half at the Danube. On the Hungarian side of the river is the town Komárom (population 19,600).Some 40,000 people live in Komárno today. The main sites - besides Euro Place and the fortification system - are the baroque Serbian Orthodox Church on Palatinova ulica, and the György Klapka square, named after the general who led the 1848 anti-Habsburg revolt. His statue at the centre of the square is decorated with flowers every March 15 by locals and by visitors from Hungary.

*Source: The Slovak-Austrian-Hungarian Danubeland, 1st edition.

Spectacular Slovakia travel guides

A helping hand in the heart of Europe thanks to the Slovakia travel guide with more than 1,000 photos and hundred of tourist spots.

Detailed travel guide to the Tatras introduces you to the whole region around the Tatra mountains, including attractions on the Polish side.

Lost in Bratislava? Impossible with our City Guide!

See some selected travel articles, podcasts, traveller's needs as well as other guides dedicated to Nitra, Trenčín Region, Trnava Region and Žilina Region.

Komárno (source: Ján Svrček)

Komárno (source: Ján Svrček)

(source: Ján Svrček)

(source: Ján Svrček)

Brdárka (source: Peter Dobrovský)

Brdárka (source: Peter Dobrovský)