The Slovak community of architects has lost one of its prominent members when architect Štefan Šlachta died in Bratislava on May 26 at the age of 76 after battling a serious disease. The funeral will take place on June 2 in Bratislava’s crematorium, the Slovak Architects’ Society (SAS) informed.

“When we were asking abroad whom they know from Slovak architecture, they mostly say - Štefan Šlachta,” architect Ján Bahna recalled for the Pravda daily. “He has brought a completely different view on architecture of the inter-war period and contributed to discovery of Slovakia’s precious modernistic architectures. His biggest merit is discovering and presentation of forgotten [Slovak] personalities of architecture [working] abroad. The history of Slovak architecture is young, not yet explored and Šlachta was one of those first who were able to explore this.”

Šlachta, born on December 6, 1939 in Ružomberok, was a student of prominent Czech architect Vladimír Karfík who designed many buildings for shoe maker Baťa in the then-Czechoslovakia. After Šlachta graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at the Slovak Technical University he became his assistant. In total he spent 13 years in proximity of Karfík.

“Here he got to know closely Baťa architecture, functionalism and the inter-war modernistic architecture in general,” recalled Bahna for the Sme daily. “The Baťa system was also a lifestyle, purity of relations and rationalisation of the environment.”

But the occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968 by Warsaw Pact armies interfered into his career too. After professors Karfík and Jozef Lacko was forced to leave the university, Šlachta had to go also. Afterwards he worked for Dopravoproject designing transport constructions. Here he participated in his most significant architectural project – designing the Lafranconi bridge over the Danube River in Bratislava.

Already when working for Dopravoprojekt he was devoted to theory and history of modernistic architecture. At that time, for example, he covered the Slovak part of inter-war modernistic architecture for the Swiss magazine about architecture Archithese, recalled Bahna.

“This was the first information about our golden inter-war period [in architecture],” wrote Bahna.

The fall of the communist regime in 1989 brought big changes also into Šlachta’s life. In 1990 he became the first president of the newly established Slovak Architects’ Society and established contacts with Slovak architects working abroad. They launched the Architecture Foundation in Frankfurt to help Slovak architecture. He also prepared the launch of the Chamber of Architects. In 1995 he became professor and later also rector of the Academy of Fine Arts and Design (1994-2000). But as his school opposed the Vladimír Mečiar government, it had problems with financing. Later he entered politics and was elected into parliament in 1998 on the slate of the Party Civic Understanding.

His last public deed was the launch of the institute of the chief architect of Bratislava, but even though Šlachta believed that he had laid foundations for such an post that used to exist here, the Office of the Chief Architect has not been fulfilling its tasks, said Bahna.

His biggest achievements thus remain in exploring Slovak architecture when he focused on personalities of the Slovak architectural scene completely forgotten in their homeland. These include, for example, Friedrich Weinwurm (who designed for example Nová Doba blocks of flats in Bratislava), Eugen Rosenberg (who along with partners led the most important architectural studio in Great Britain in the 1960s and 1970s which designed, for example, Gatwick airport; but also Ladislav Hudec who designed and built the first skyscrapers in Shanghai. He published results of his research in books Unknown known (Neznámi známi) and Return of those who left (Návrat odídených). His research and publication works earned him the Award of Emil Belluš.

Šlachta in Petržalka

Šlachta considered himself to be a modest man. Even though he was a recognised architect, he lived in a flat in a housing estate in Petržalka.

“I’ve never zest to present myself by a super house even though many are saying that an architect should have such one,” said Šlachta as recalled by the SITA newswire. “I grew up in a family house and know how much work there is around a house.”

Šlachta recalled a visit to a friend of his in Finland living in a two-room flat in a housing estate, who told him that even though he can afford better housing he did not have a reason to move as he was living in a very pleasant environment with a lake next to his house; in winter he could ski right from his home. This experience led Šlachta to present Petržalka as a city’s borough with functions for a full-fledged life, not only as a housing estate for dwelling. For this he was awarded the Personality of Petržalka in 2014.

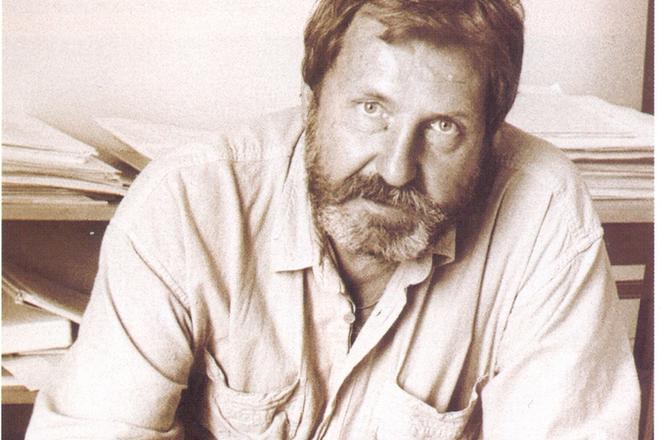

Architect Štefan Šlachta (source: SAS)

Architect Štefan Šlachta (source: SAS)