The museum, residing in the only still preserved and functioning synagogue in Bratislava, has one permanent exhibition and one temporary exhibition which changes every season. This time around, the exhibition called Each Family Has Its Story tries to present objects preserved in the families of 20 members of the Bratislava Jewish community and to connect them with a specific person and his or her story.

“Today, we do not tell stories, they are often replaced by social networks, by the internet,” head of the museum, Maroš Borský, said at the exhibition opening, adding that items bear memories connected with them. The items shown include artworks (a paintings, a textile collage) and religious instruments (scroll – or megillah – of Esther, a mezuzah, etc.) but also everyday tools like glasses, cutlery, clothes hanger, a carpet remembering six generations, scissors, a watch, and so on, which are connected to a person through some kind of story and which are sometimes also the only evidence of the person's existence for the younger generations. Owners, makers and finders of these things often perished before the descendants were born, or are remembered only vaguely.

This can be true in many families and many cases, especially in countries that experienced world wars, as Slovakia did.

Jews’ fates in Slovakia

However, in Jewish communities, such cases are more the rule than an exception, not to mention that sometimes whole branches or whole families were killed within a short time, during the Holocaust.

“In 1940, the Bratislava Jewish community had 15,109 members,” co-author of the exhibition (with Monika Vrzgulová), Peter Salner, said. “By 1945, there were 3,500 of them – and many of them were Jews from other parts of the country who moved here.”

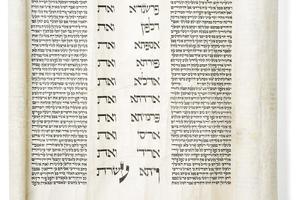

One such case was the family Preis who were deported from Sabinovská Street in Prešov during World War II. After they returned, they found the almost all their belongings were aryanised (i.e. seized) or simply stolen – only those without much value were left. Katarína Samolovič, the aunt of the current owner, Ivan Pasternák, rejoiced when she found the scroll of Esther belonging to her mother at the bottom of a closet, wrapped in old, ragged clothes. The scroll was valueless for Christians but of great importance for the family.

This megillah, apart from the emotional tie for the family, has also a huge importance for the Jewish communities and has been used by two of them, first in Prešov and then in Bratislava.

Living abroad

Apart from those who came to the capital from other places, there were also many survivors who left the city for other locations, usually abroad. This is the case of Thomas Frankl, son of painter Adolf Frankl who was born in Bratislava but later left to live in Vienna; not so far from the city he felt connected to. The painting by Adolf Frankl, called Our Arrest in Bratislava, shows the detention of his family. “Father did not want to leave the city he loved and could not believe the same bad things that happened to Jews in Germany and Austria would happen also in Slovakia,” Thomas said during the opening. “Fortunately, he survived. But on Jom Kippur when also our uncle came, our family was driven out of our flat and across the city centre – a true Via Dolorosa for us, with a woman shouting in the Panenská Street “They deserved this!” Then, at the railway station, mum – a beautiful and bright woman – started talking to a German soldier and claimed we were a Christian family and father was detained by mistake.” Thus, they were given accompaniment and survived, with the help of locals.

Some of the other items are a painting of the synagogue in the Czech town of Kroměříž that was bombed in 1942, or a Persian carpet of the Shirvan type which was one of the few things a Jewish girl who survived the Holocaust was allowed to take when forced out of the house of her parents.

Some of the items testify of a relatively happy ending when the owners survived the war and could keep them, while some others commemorate people whose place in the family remained vacant after a violent death.

In one case, the commemorative item, a watch, was thought to bring luck to the survivor – the mother took it instead of her broken watch to work one day... and as she worked with forged documents and was reported by one woman as Jewish, she was deported to the Czech camp in Terezín and returned with it after the war. She considered it a good-luck charm but gave it back to her son who left for Israel in 1949.

The items are completed with photographs of their owners, often whole families, and also with stories.

It is advisable to also consult the bilingual catalogue of 75 pages which sums up the relatively small, intimate exhibition that runs until October 8 – on Fridays and Sundays, except for Jewish holidays – in the Jewish Community Museum in the synagogue on Heydukova Street.

Adolf Frankl: Our Arrest in Bratislava - The Leaders of Evil (source: Courtesy of Jewsih Community Museum, Bratislava)

Adolf Frankl: Our Arrest in Bratislava - The Leaders of Evil (source: Courtesy of Jewsih Community Museum, Bratislava)