At the foot of Slovakia’s Štiavnické vrchy hills, a long-forgotten hilltop settlement is giving up its secrets. Using state-of-the-art aerial scanning technology, researchers have uncovered remnants of stone structures and terraced fields stretching down the valley slopes – evidence of a rich and complex past. Their precise age remains a mystery, writes the My Levice website.

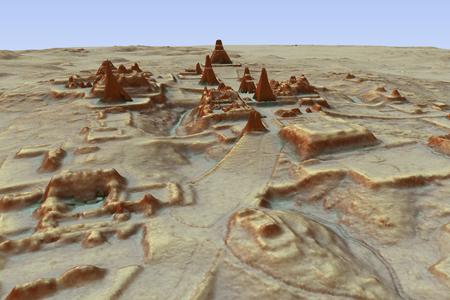

A team of geoinformatics experts from the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava has mapped the 140-hectare site using LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), an advanced laser scanning system.

The technology has not only exposed previously unknown locations but also shed new light on prehistoric fields in the Liptov region, including a vast fortified settlement dating back 7,000 years.

A forgotten fortress in the woods

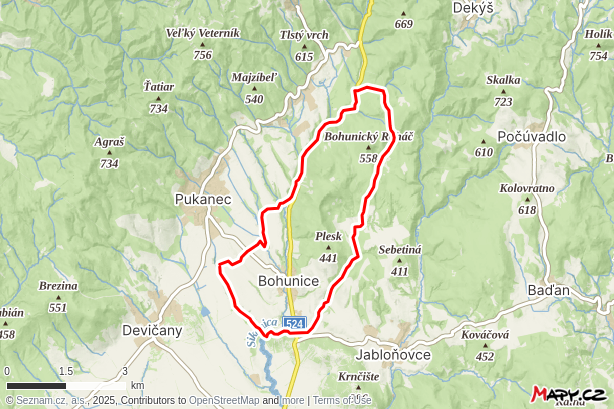

Hrádok, a historic hill behind the church in the village of Bohunice, was inhabited as early as the Stone Age. After the Tatar invasion in the Middle Ages, a fortress was built here to guard trade routes leading to mining towns such as Pukanec and Banská Štiavnica. According to the village monograph, the site later became part of an early warning system against Ottoman incursions – and offers evidence that the steep slopes were once used for viticulture.

“If you approach from Pukanec, you can still see the stone terraces,” says Vladimíra Rišková, mayor of Bohunice, a tiny village of just 155 residents.

Today, while some locals still cultivate vineyards, much of the land has been reclaimed by the forest. The ruins of the fortress remain concealed beneath the trees, with an old stone wall protruding from the earth. Similar fortifications were common across what is now Slovakia between the 12th and 15th centuries.

Tracing lost landscapes

Hrádok itself spans roughly 17 hectares, but the terraces extend far beyond, following the slopes of the Sikenica valley.

“You can see numerous terraces, as well as remnants of stone heaps – piles of stones marking ancient vineyard boundaries – and traces of vanished cellars and dwellings,” explains Tibor Lieskovský from the Department of Global Geodesy and Geoinformatics at the Slovak University of Technology.

South of Bohunice, researchers have identified even larger historical landscapes near Jabloňovce. Nearby, in Pečenice, lies the so-called “Wall of Giants” – a massive embankment stretching several kilometres across the countryside, believed to date back to the early Middle Ages.

Revealing the invisible

LIDAR technology, which measures distances using laser pulses, has revolutionised archaeological research.

“It works similarly to how bats and whales navigate their surroundings, using the time delay between an emitted and reflected signal,” Lieskovský explains.

By virtually stripping away the forest cover, the scans have uncovered a wealth of features invisible to the human eye – including burial mounds, ancient roads, mining sites, charcoal kilns, battlefields, and lost agricultural systems.

“We’ve detected previously unknown hillforts, as well as forgotten structures within known castles – ramparts, moats, and defensive lines,” he adds.

In the Veľký Tribeč region alone, heritage officials have identified more than 11,500 archaeological features across a 260-square-kilometre area. On Slovakia’s eastern plains, the scans have enhanced knowledge of Bronze Age burial mounds, tracing them across a 90-kilometre stretch of land.

Yet even cutting-edge technology has its limits. “We can detect tens of thousands of structures, but we only see their surface remains. Determining their age usually requires excavation,” Lieskovský cautions.

For now, archaeologists must take on the challenge of piecing together the fragments of this newly unearthed history.