After losing much family in the Holocaust, Frank Lowy left his birthplace. He became a multi-billionaire and a philanthropist, but kept returning to Fiľakovo, a town in southern Slovakia, looking for traces of family. He restored the cemetery and, on the site of the demolished synagogue, erected a memorial to its lost Jewish community. As this community, including his father who perished in the Holocaust, had supported the town’s football team, so did he. Sir Frank Lowy has been knighted by Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth, and he holds the highest civilian honor of Australia and Israel, and the Gold Plaque of Minister of Foreign and European Affairs of Slovak Republic. When Slovakia apologized for the tragedy unleashed on its Jews, something in Frank relaxed.

Frank Lowy’s story is part of a Global Slovakia Project- Slovak Settlers, authored by Zuzana Palovic and Gabriela Bereghazyova. The book is available for purchase via info.globalslovakia@gmail.com.

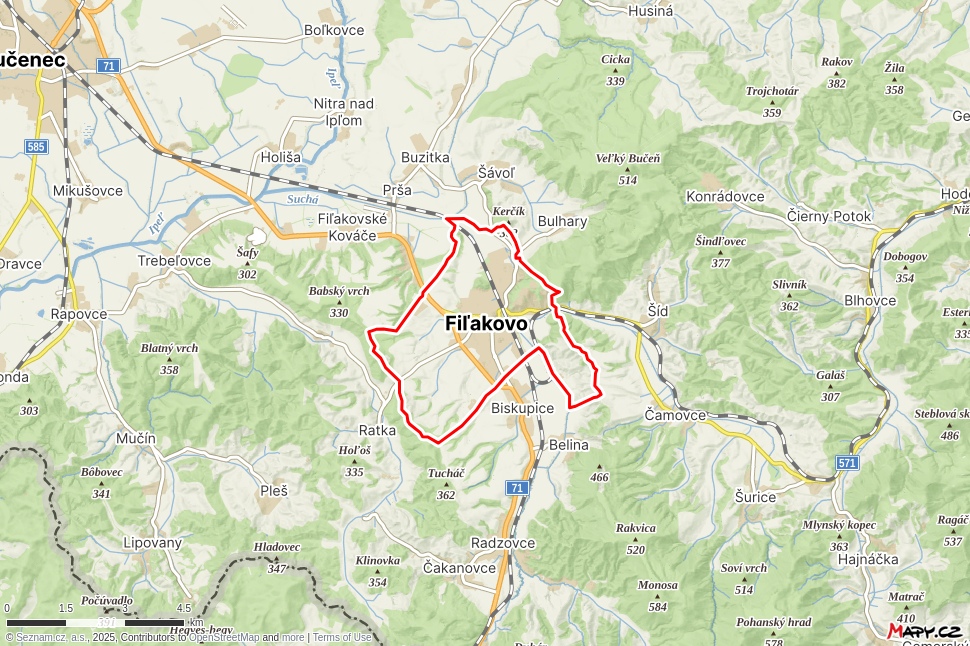

I was just a boy when World War Two disrupted my universe, pulled me out of my small Slovak hometown, and took me away from everything I knew. Since then, I have returned to Fiľakovo many times and walked its streets, trying to remember the smell of those sweet years before things turned ugly for the Jewish community of Slovakia.

I am 91 as I write this story. I am sitting in my study in Tel-Aviv, freeing my mind to float back to Fiľakovo in 1930, where I was born into a close-knit religious family, surrounded by a Jewish community of about 200 souls. They were my whole world. We and the others followed the Jewish calendar religiously, which centred around the local synagogue. Everyone contributed to its upkeep and towards the rabbi’s salary. It was called a ‘culture tax’. But let’s return to me and my family.

Although I was born in the depths of the global depression, we were always clothed, fed, and educated. Our lives were simple and wholesome. We had fruit trees, grew vegetables, and drew water from a large handpump in the garden. I was bathed on the kitchen table, and us four children shared beds. From the front room facing the street, mother ran a grocery store selling sugar, bread, flour, and other staples. Bells were attached to the door and whenever we heard them tinkle, we knew a customer had arrived. I used to hear it a lot. As the youngest child, I spent most of my time during the first years of life with my mother.

Her family, the Grunfelds, hailed from Revúca where they also ran a grocery store. The highlight of our year was taking a train to visit them in the summer. I still remember carefree play with my cousins, especially with the blue-eyed girls Renée and Rebecca. Our families didn’t meet very often, but the distance between us was bridged with weekly letters full of domestic details and words of love.

My father, Hugo, was born into a large family of a former teacher. His father gave up teaching to become an innkeeper, so he could better support his family. The family moved to Fiľakovo where they lived behind the inn. When he passed away, my grandmother remained there with her daughter and family. Our lives were interwoven with theirs, and mother would often leave me to play with my cousin under the watchful eye of my grandmother.

Most of us lived humbly, but my father’s brother, Leopold, was one of a handful of wealthy men in Fiľakovo. He earned his fortune by running an exclusive agency for the products made by the town’s stove and kitchenware factory. Leopold lived in a big house that we only visited once in a blue moon. I did not care much about that at the time. What fascinated me was his car in which I never got to ride. I had to manage with a bicycle that I was allowed to use to run errands for mother’s shop. I was so small, I had to ride under the cross bar.

By 1936, it was time for me to attend school, play soccer with a ball made from socks during breaks, and head to a Hebrew class after school when the other children went home. I had to go on Sundays too, but occasionally a miracle happened. On those memorable days, father would turn up, talk to the Hebrew teacher and the next minute, I was released. Holding father’s hand, we walked across the fields to the local soccer ground where the team of Fiľakovo, famous for its prowess in the district and beyond, was playing. Men of the Jewish community were big supporters and would sit together on the stand.

It is one of my most cherished memories to be there with father, freed from Hebrew class and watching our team surrounded by men we knew well. I treasure that moment, because I did not see much of my father in those days. He was impacted by the Great Depression and had to work as a travelling salesman for his brother, Leopold, during the week to make ends meet. He returned on Fridays, and I ran home after school to wait for him. Seeing him walk through the door gave me boundless joy. Sometimes, I would even wait at the railway station near our house and run into his arms.

It was a tranquil time in Fiľakovo. Although everyone knew we were Jews, for my first seven or so years, we were not harassed, and there was no official anti-Semitism. There were other minorities in our town too, but we rarely interacted. As far as possible, the Slovaks, the Hungarians, the Roma, and the Jews all kept to their own.

The country was led by Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, a liberal whom we trusted and who appreciated the Jewish culture. In 1935, Edvard Beneš followed Masaryk’s lead. He was a genuine liberal democrat, and we felt protected. But then came 1938, and the earth beneath our feet started to tremble.

Great geopolitical forces were at work, and there was nothing we could do to stop them. Under the Munich agreement, Germany gained permission to occupy the Sudetenland, the areas in the Czech lands that were a home to a large German minority. This happened just before my eighth birthday, and it left us exposed and nervous. Czechoslovakia was wounded, and soon Poland and Hungary would also start claiming a share of our weakened country.

Any remaining sense of security was shattered a few weeks after my birthday. The news of Kristallnacht, a pogrom against Jews throughout Nazi Germany, came as a shock. I could feel anxiety in our community. It was just the beginning. Soon after, Hungary took the Magyar-inhabited southern part of Slovakia and Carpatho-Ruthenia, and Slovakia claimed independence from Prague. All I could feel was raw fear.

In the turmoil, the borders closed and our annual and much looked forward to holidays to Revúca, now under Slovak rule, stopped. Our town fell under Hungarian rule and anti-Semitism rose steeply every day.

Suddenly, Jews were deprived of opportunities to work and own businesses or property. Mother was forced to take a non-Jewish partner into her grocery shop, so his name could appear on the license instead of hers. It was no longer possible for us to keep our heads down and get on with life. In such a small town, we became an immediate target. My friends and I were harassed on the way to and from school. It was humiliating and I was afraid, but I knew I could not afford to show weakness.

Uncle Leopold was forced to take a business partner too, but with Slovakia cut off and the future uncertain, trade was declining, and many were out of work. When Father lost his job, our house was at risk of being repossessed. I remember how distressed my parents were, but I also recall the enormous relief when mother’s family came to the rescue. Her brothers filled a couple of suitcases with cash, traversed the border, and arrived in time to pay out the mortgage and save our house. The memory of that unquestioning family support—the warmth, generosity, and kinship. The feeling that when in need, the family would provide, has remained with me ever since. It is imprinted in my mind. Any problem for one was a problem for them all.

In 1942, we received chilling news. As part of a general roundup of Jews in Slovakia, mother’s family was being deported. Several letters described the deportations and in April, mother opened a heartbreaking letter from her brother Géza. He was in despair about the plight of the children.

‘I would very much like to ask you if you could take our dear children to be with you. Although I know you are not in an easy situation, one only pities the little ones. We can manage somehow. We could arrange to get them to [word deleted by censors] and you could come and meet them there, if we are still here at that time.’

Without a moment’s delay, my parents despatched a trusted non-Jewish woman from the village to go towards Revúca to collect the children at a place near the border. The woman had cash to secure their passage, but they never arrived. The family had been deported the day before. In total, four families, each with three or four children, had disappeared and little information was available about where they had gone.

I was 11 and tried to imagine what might have happened to Renée and Rebecca. How could we help them? Mother was distraught. She spent much of her days crying and praying. There was a letter from one of the families and for a couple of months she held hope, but no letters followed, and eventually, mother was overcome by uncontainable grief. Sadness pervaded the house, with each child feeling the heavy weight of the immense loss. I was becoming aware of the precariousness of our existence and of ominous forces at work.

A few months later, Father decided we should move to Budapest where it would be easier to blend in among the one million inhabitants. The then-regent of the city was relatively protective of the Jews, allowing discrimination, but within limits. Our house and shop were sold, we packed up and joined our extended family that had been in Budapest for a year. After lodging with them for a few weeks, we found an apartment with a bathroom and heating, which was luxurious for us.

But my oldest brother, Alex, couldn’t join us. He had been drafted into the Hungarian army as a labourer. Mother ran our home; I went to school; and Father, my older sister, and brother all found work. In some ways, this period was an interlude of happiness for us. Despite considerable anti-Jewish sentiment and restrictions, we could live openly. I could still go to school. Some Sundays, I even attended soccer matches.

The fragile equilibrium was blown apart on Sunday, March 19, 1944, when the Nazis entered Budapest with the sole intention of ridding Hungary of Jews. When I close my eyes, I can still see the fright in my parents’ faces. They talked all night, plotting a way out of this impasse. In the morning, father went to the railway station to buy tickets to move us to the provinces, but his arrival at the station coincided disastrously with a raid by the secret police.

For days, I stood on the sofa next to the window, looking down into the street, hoping to see him returning. We never saw him again.

We did not know where to turn. A relative suggested we buy false papers and split up. That is what we did, but there were no papers for me. As my sister and brother went off separately, mother and I went into hiding. Stories of our family’s survival could fill an entire book…

Eventually, Budapest was liberated, and we found each other again. My oldest brother returned from the war, and the five of us clung together, waiting for father. Every day, we checked the Red Cross lists, questioned returning survivors, and followed all possible leads. As hope faded, we could see no future in Budapest and, with heavy hearts, we turned for ‘home’. If father were alive, he would surely find us in Fiľakovo.

Jews had begun trickling back from the camps, and although only around 30 returned to Fiľakovo, none were welcomed, and none were spared the details of what had happened when the town was ‘cleansed’ of its Jews. When I heard what happened to Uncle Leopold, I could not sleep at night, and I knew this was not a place for us. Although he had lost his money by 1943, he was accused of hiding it and brutally beaten for not producing it. His body was broken and, barely conscious, he had to be carried to the trucks waiting to transport the Jews to a larger town, before sending them on to Auschwitz. This could no longer be our home. We packed our few belongings and went to Lučenec to turn over a new leaf and start again.

One of my brothers opened a shop there, and my sister met a lawyer called Paul Weiner. They married and began planning to move to Australia, but my other brother Janko was restless. He felt he had no identity. Although he was a Czechoslovak citizen, he felt neither Czech nor Slovak. He certainly did not feel Hungarian. He saw his future in Palestine, where he could recreate himself, be born again. As he left, he said, “In Palestine, I can be part of something I could claim as my own.”

Soon after he left, Mother recognized the desolation of our life in Europe and said I should join him. To this end, I went to a Zionist-funded camp in Košice where I was taught about Palestine and Zionism. The Jewish Agency had for some years been organizing escape routes from central Europe to the Mediterranean where it bought or chartered ships to Palestine. There was nothing for me in Czechoslovakia—only bleak memories. What is more, I had missed many days of school and was not motivated to catch up. I also felt a huge inner pressure to leave. Palestine offered a new beginning and a chance to be part of the Jewish drive to create a homeland.

I said goodbye to mother in early 1946. The sadness of separation was tempered with the hope of something new. Through the pain of parting, she assured me that we would all meet again in Palestine. I travelled by train to Prague and then Paris with two dozen youngsters, chaperoned by the Jewish Agency. Just south of Marseille, at the port of La Ciotat, we boarded a ship that had been patched together and was barely seaworthy. Designed to carry 100, it had more than 750 souls on board with little food or water.

During one stormy night, it finally dawned on me what my decision meant. Mother had always been the still point in the turmoil of the world, and now I was alone, seasick, and frightened. I couldn’t seek comfort from anyone. I was 15 and I was crying on the inside. When I stepped ashore in Palestine, there were no questions, just an unspoken promise of belonging. I joined a small group of boys and girls who had survived the Holocaust and together. We worked in the fields in the mornings, attended lessons in the afternoons, and had our evenings free. It was a healing time for me.

Things changed dramatically in late-1947. The United Nations voted in favor of creating a Jewish State. The local Palestinians and surrounding Arab countries were in violent disagreement with this decision, and in 1948, when David Ben Gurion declared independence, they all combined to attack the new State of Israel. I had just turned 17 and signed up immediately to fight for the Biblical homeland I had learned so much about in Košice. Willing to endure any hardship, the group to which I belonged was selected to join the first commando unit in the Israeli army. As part of the Golani Brigade, it operated at night, behind enemy lines.

When the war was over, I found work on building sites, then worked in the post office while attending night school to learn accounting. That helped me secure a job in a bank. I was living with my brother Janko. Our free time was devoted to soccer, and life seemed to be “normal” again. Although I never said it out loud, every match took me back to father. We also missed Mother, more than words can describe.

Mother and other members of the family had moved to Sydney, Australia, and we yearned to be reunited. But Israel was brimming with youthful optimism, and we also wanted to stay. We agonised over the decision, but the pull of family was irresistible and in January 1952, I rushed into mother’s arms at Sydney airport. All I possessed was a small suitcase and a debt to cover my airfare to Australia. Soon I was delivering smallgoods all over Sydney. This job came with a small commission. The more I delivered and sold, the more I would make. So, I never stopped.

That year, at a party to celebrate the Jewish festival of Channukah, I met a beautiful 18-year-old lady called Shirley Rusanow who, for the next 66 years, would become my life partner. While I worked as hard as was humanly possible, she looked after our three sons, David, Peter, and Steven and ran our home. Shirley was our center of gravity, and while business often took me away, she was always there. She was my home.

Life went on, and I entered into a business partnership with an older European émigré, Janu Schwartz. It started as a small delicatessen. Over time, we grew it into a shopping center called Westfield, which then spread across Australia, into America, and the U.K. On some metrics, it became the largest retail real estate company in the world. My sons and I worked together like a business machine driving the company forward.

My love for soccer never faded. As my father had done for me, so I had ignited a passion for soccer in my sons. By 2003, Australian football (soccer) had fallen into disarray and its administration had collapsed. When I was asked to restore the sport to a professional level, I did not hesitate, first rebuilding the domestic league, then strengthening the national team and seeing it qualify for three successive FIFA World Cups. Soccer remains central in our lives and for me, it will always be an unbroken link to Fiľakovo.

For personal comfort, I always carried a photo of mother and father in my wallet to remind me of what was lost and why I should live life to the fullest. I also carried a photo of my blue-eyed cousins Renée and Rebecca. In the late-60s, these images were with me when I took Shirley to Fiľakovo for the first time. We stood on the pavement and looked at the old house.

I felt nothing. We walked to the railway station. Still nothing. Then I found the place where the Synagogue had stood, but there was no trace of it. The Communist Party had erased it from the map. Over the years we went back to Slovakia a few more times, finding nothing. Then, when the communist regime fell, there was a lighter mood in the town, and we braved to knock on the front door of our old house. To our amazement, we were invited in.

Suddenly, it all came alive for me!

I remembered it all, and with that, felt the stirrings of a connection. I went back a few years later, this time with my sons and their wives. Just as we were leaving the town, we noticed the derelict Jewish cemetery and stopped. My sons and I climbed its high fences and found it overgrown with stones that had long since fallen. After an hour of clearing weeds in the sun, we turned over the headstone of Jonah Lowy, the grandfather and inn keeper I had never known. We set his stone upright and stood in silence, each aware that four generations of Lowy men were in one spot. Only father was missing. In faltering voices, we recited Kaddish, the traditional prayer for the dead.

The cemetery was the only sign that Jews had ever lived in Fiľakovo. It was an opportunity pleading to be taken. Janko agreed to fly there and stay a couple of months to arrange for it to be restored. This project awakened interest in the townsfolk and was, I think, the beginning of the recognition of what was lost.

By then, I had learned that Father had perished at Auschwitz for refusing to forsake his faith and in 2010, I managed to create a private memorial for him at the place where he died. With that, a part of me relaxed, but something was not right yet. So, I went back to Fiľakovo. There is a small park where the synagogue once stood. I placed an obelisk and dedicated it to the memory of our community that had been there since the early-1800s. The town enthusiastically organized a ceremony and with this, the lost community was acknowledged.

With my community recognized, I feel comfortable in Fiľakovo again. I eat in its restaurants, and I am touched by the museum displays that show a few artefacts someone had saved from the synagogue before it was destroyed. One of these artefacts is a seating plan that shows where my father used to sit. I would like to thank Edita Berntsen a Slovak immigrant, lawyer, and Honorary Consul for Slovakia in Sydney, who has helped coordinate my reconnection on to Fiľakovo for the past 20 years.

When I was signing a contract for the town to maintain the memorial, a local citizen, Peter Sáfrány, offered to look after the cemetery as an act of grace. He asks no payment, but as we share a passion for soccer, I sponsor his club and the team I followed as a boy. That is another cycle closed. Thereafter, I returned every year or so, bringing my grandchildren so they would know the story of their family.

In 2018, Shirley and I moved to Israel to live. She passed away peacefully in 2020, on the eve of the Jewish Festival of Channukah.

In 2021, Slovakia apologized to its Jews for the tragedy unleashed on them during those fateful and tragic years. As someone who lived through the sad times and survived the Holocaust, I appreciate this gesture and regard it as significant.

Matzo Balls (Kneidelach)

Ingredients:

2 large eggs

½ cup cold water

cup olive oil (traditionally, chicken fat was used)

½ tsp salt

pinch of pepper

finely minced parsley

1 cup matzo meal (ground-up matzo, a traditional Jewish unleavened bread)

Steps:

1) In a large bowl, beat the eggs with a fork. Mix in the cold water and the olive oil.

2) Add salt, pepper, and parsley, and mix well.

3) Add the matzo meal and blend well.

4) Cover the bowl and refrigerate for 2-3 hours. The consistency will change.

5) Moisten both hands and form the mixture into balls about 1” in diameter.

6) Drop the balls gently into a big pot of boiling chicken broth.

7) Reduce the heat and let simmer for 30 minutes or more. The matzo balls will rise to the top. (If you make the balls bigger than 1”, simmer them longer.)

8) Carefully remove the matzo balls from the broth with a slotted spoon, place them in a large bowl, then gently pour the soup over them.

Frank Lowy (source: Courtesy, Frank Lowy)

Frank Lowy (source: Courtesy, Frank Lowy)

(source: Courtesy, Frank Lowy)

(source: Courtesy, Frank Lowy)

(source: Courtesy, Frank Lowy)

(source: Courtesy, Frank Lowy)