Originally from the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area, Albert Kovanis, Jr. gained his MBA at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh and went on to have a long career as an accountant. He retired after 52 years and relocated to Northern California with his wife. Al continues to cherish family traditions and stories and hope hopes that his three children and their children will continue to explore and preserve their shared Slovak heritage.

Al’s story is part of a Global Slovakia Project- Slovak Settlers, authored by Zuzana Palovic and Gabriela Bereghazyova. The book is available for purchase via info.globalslovakia@gmail.com.

I am the second child in a family of 12 children born between 1947 and 1971. My early life was shaped by the faith and guidance passed on to me from my parents and grandparents. My mother’s family had roots in several European countries, but my father’s parents, who were more recent immigrants, were proud to state in their soft-accented voices that they were Slovak.

My school geography lessons taught that Slovaks and Czechs lived in the country of Czechoslovakia, based on the system of Soviet communism that was much different from the democracy we lived in. Czechoslovakia was an ally of the Soviet Union which made it our ‘enemy’ during the Cold War.

Although my Slovak grandparents were smart, hardworking, and loving, I was uncomfortable telling anyone that they came from Czechoslovakia. As a result, my Slovak heritage was kept mostly hidden. I didn’t try to find out more about the origins of my family. It was enough for me to know that I was American. It wasn’t until later that I discovered the rich Slovak culture and felt proud of my Slovak family legacy.

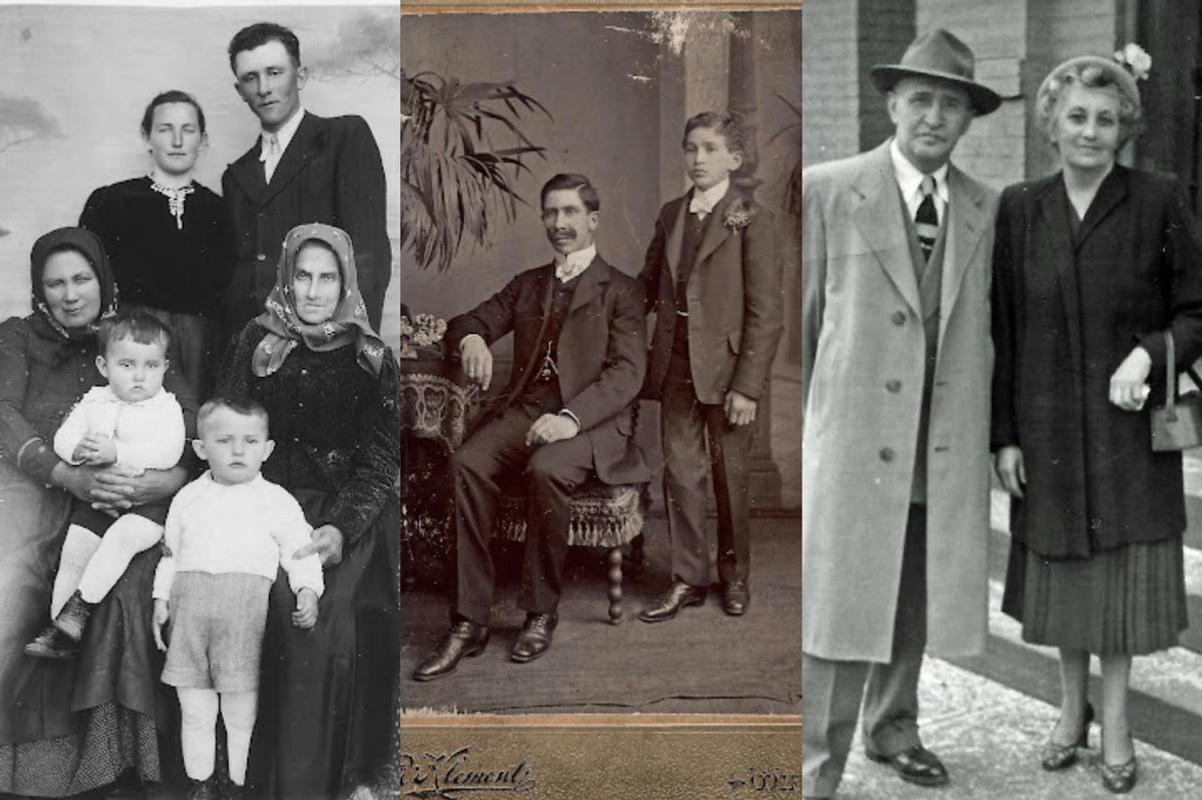

Felix Kovanič and Johanna Kovárik left the comfort of their family to come to America at the beginning of the 20th century. With confusingly similar surnames, perhaps it was in their destiny that they would end up together. They could not have foreseen or predicted the events and great adventure that their futures would bring. This humble couple from simple peasant stock would live extraordinary lives.

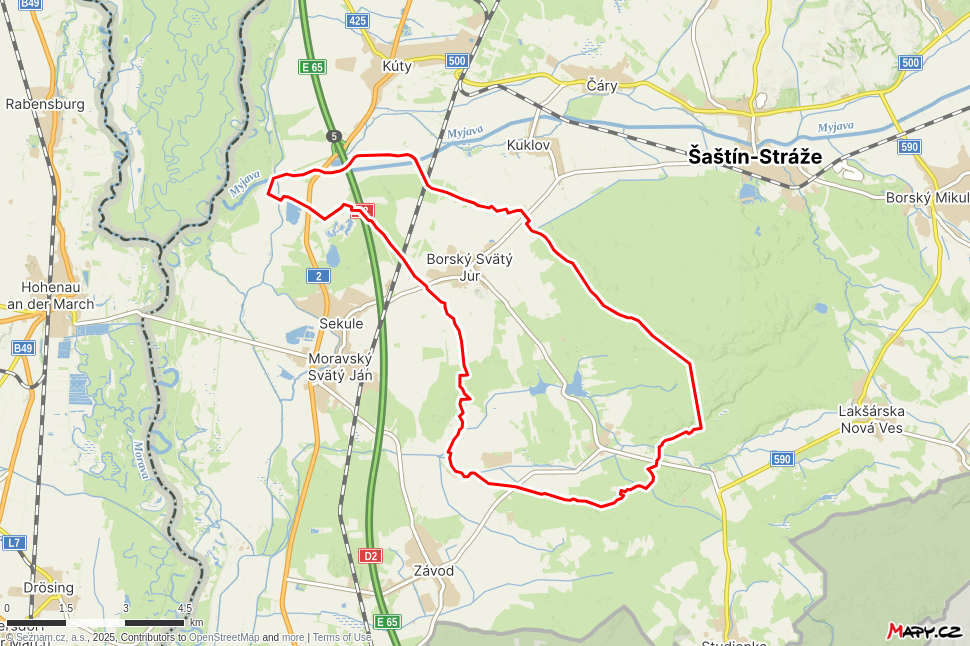

Their home was the region of Záhorie in western Slovakia, between the Little Carpathian Mountains in the east and the Morava River in the west. Politically it had been part of the Kingdom of Hungary for centuries. It was also home to diverse ethnic communities, who preserved their identities as Slovaks, Czechs, Germans, and others. This is not just historical trivia, but a legacy that lives on in my blood.

The family history of my grandfather Felix is no less intricate. Felix Kovanič, the seventh child of his parents, was born in 1895 in the small village of Burszentgyorgy. Today this village is known as Borský Svätý Jur. The local records reveal that the surname was present in this part of Slovakia for at least a half dozen earlier generations of serfs tied to the land. But it is very possible that these people had been living there for much longer than that.

The area received Croatian settlers in the 16th century when the mighty Ottoman armies sprawled across the Balkans and even invaded the Kingdom of Hungary. As they advanced in the direction of the territory of what is today Slovakia, they pushed people from the conquered lands north. Many found refuge in modern day Slovakia, then known as Upper Hungary, which never fully fell into Ottoman hands.

Does the “ič” ending of my family name indicate that its origins are in the Balkans? Were my forefathers among those who escaped the invaders and settled in Upper Hungary?

Felix’s father Georg married a young woman from an ethnic German family that lived in a nearby village. The issue was that Genoveva had an illegitimate son. During a time when single mothers had to face much prejudice and judgement, perhaps it was easier for the couple to move away and start anew.

Eventually, they settled in Borský Svätý Jur, where my grandfather was born. Once the family had a permanent home, Georg who was a tinker, travelled to America for work. When the father of the house was away, the responsibility to look after the family rested on the shoulders of Genoveva and the eldest son Nicolas.

Sadly, in 1898, when my grandfather was only three years old, his mother died from tuberculosis. His brother Nicholas was no longer living with them. He had married and moved to Vienna, Austria, to be close to the family of his wife. Felix’s father understood he needed someone to care for his children, and so he re-married quickly. Georg chose a widow with children of her own before he returned to America to work. Soon after, he received a letter telling him that Felix was bullied by the children of his stepmother.

Being far away in America, Georg swiftly dispatched his son Nicolas to check out the situation. Nicolas told his stepmother to pack Felix’s clothes and took his young brother to Vienna where he raised him as a member of his own family. Later in life, when we asked granddad about his early years, he would smile and simply say, “Aah … Vienna!”

Nicolas ran a grocery in a prosperous neighborhood near the imperial palace Schönbrunn. Nicolas and his wife Juliana had six children, and Felix was raised by a loving family. He learned to speak and write German fluently which became a useful skill when he came to America. He also helped in the grocery store, and his big brother made sure he received a good education.

Felix was enrolled in a prestigious trade school in Vienna where he learned mechanical skills. When he graduated in the fall of 1912, he was at the age for conscription into the Austrian army. But Georg stepped in and arranged for his youngest son to join him in America. He believed America offered much better opportunities than the Austro-Hungarian army.

Unlike many others, Felix did not leave from a German port, but rather travelled via the French port Le Havre in January 1913. He disembarked in New York City and continued to Wheeling, West Virginia to join his father.

Now let’s take a pause and trace the story of my grandmother Johanna Kovárik. Johanna was also born in Záhorie to the family of a forest ranger. Johanna was a sturdy young woman and her mother made sure she learned all the skills necessary for running a successful household.

Gram would tell us that life in Gbely was not easy for the Slovaks. Her school classes were taught in the Hungarian language, and she was forbidden to speak in her native tongue. Getting caught talking Slovak in school led to a whipping; a stern warning not to do so again. So, Johanna stopped going to school and stayed home with her mother instead.

At that time, many were leaving the village to seek better opportunities in the New World, including Johanna’s cousin. She wrote to Johanna and invited her to visit. She promised there was much to see, and they would have a great adventure in America together. Resolutely, Johanna’s parents told her no, but she persisted in asking and finally gained their permission to go. Johanna’s oldest brother, Jan, agreed to loan her enough money for the journey if she promised to repay him. She took the money, and Jan was repaid to the last cent.

As Johanna was leaving for her trip, she received a valuable final piece of advice from Jan. “Don’t believe all the things the boys will tell you!” And with that, the great adventure began. Johanna traveled in a group with seven others from the village, chaperoned by a second cousin.

The youth made their way to Hamburg, Germany and boarded the ship appropriately named America, a good omen. The ship was filled with people from all over the place, but Johanna kept to herself with the other Slovak passengers under her chaperone’s watchful eye. Traveling in steerage, the part mostly below the ship’s waterline, was the first test of her resolve. Light came in only through the ship’s portholes. It was hot and smelly, and Johanna would try to sneak out of her area to the upper decks whenever she could to find at least a temporary relief. This was against the ship rules, but occasionally the crew would take pity on the young girl. She was able stand on an open deck for a short time to get a breath of the fresh ocean air.

Food was scarce and would be shared within groups traveling together. Once, a fellow passenger came into possession of a banana. Since no one had ever seen one before, there was much curiosity about how to eat it. The lucky possessor of this mysterious delicacy simply bit in and ate the whole thing in a few bites, banana peel and all! There was no waste in steerage, and at least one growling belly was quieted for a short while.

It took two exhausting weeks to cross the ocean, and all the passengers were happy beyond words when they finally sailed into port past the Statue of Liberty. Everyone cheered and many eyes filled with tears when they saw this wonderful sight.

Johanna successfully passed through the immigration control at Ellis Island pretending she was 18 (when she was actually 15 years of age). She then found the railroad station and boarded the train to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. When she got off the train, Johanna was greeted by her cousin’s parents, and taken to the nearby town of Carnegie.

However, this was not going to be a holiday. A few days later, Johanna was told that she was expected to pay for her share of the household expenses. So, she made do and found a job as a maid, to the widow of a wealthy industrialist. Before long, her short vacation to the United States turned into months and then several years.

Although she missed her family dearly, she also enjoyed the excitement of her new home. Moreover, the eruption of the First World War made returning to Slovakia impossible. The homemaking skills that Johanna learned from her mother were put to good use. She contributed some of her earnings to support her cousin’s family, and the rest of what she earned was saved to repay the travel expenses and, perhaps, to buy a ticket back someday.

I do not know what 17-year-old Felix Kovanič, or 15-year-old Johanna Kovárik expected to find when they set out for America, but, I know that the most important thing they did was find each other.

When war broke out in Europe, Felix was working with his father in the mills along the Ohio River. Georg wanted to return to be with his family in Hungary, but it would be dangerous for Felix to go with him because he would be drafted into the military service. Felix was doing well at work and had the skills to support himself in America. He wanted to marry, not die on a battlefield!

Sunday was always a day of fun and rest. On one such Sunday, Johanna and her cousin went to Bellaire, Ohio for a Slovak picnic. Bellaire was on the opposite side of the Ohio River from Wheeling, where Felix lived.

There, she met a nice young man named Felix and they were immediately smitten with each other. Soon they got engaged, and in August 1915, the young couple was married in a Slovak church in the same town. It was the beginning of a happy, loving marriage that would last 53 years.

The couple settled in Carnegie, a fine place to find work and raise a family. There were many opportunities for work in the steel mills, coal mines, or railroads. Pittsburgh was just a trolley-ride away and there were plenty of fellow immigrants who formed their own churches, social organizations, and just helped one another.

Felix and Johanna quickly settled into their new community. They lived in an Irish neighborhood, and although some Slovaks also lived in the area, they were few and far between. There was also no Slovak church there, a pillar of Slovak communities in other parts of Pennsylvania. Hence, the couple became active members of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church that was built and supported by the local German community. Felix’s ability to speak German from his Vienna days really helped them to fit in.

The Concordia Club was a favorite social spot for them. That’s where local Slovaks gathered to relax after work and to meet with their friends. On Saturday nights, they sang and danced to familiar songs and downed more than one warm beer! Johanna also joined the Sokol organization where she practiced gymnastics. She served on many Sokol committees and even held the office of Financial Secretary Treasurer for 55 years.

Felix had well-developed mechanical skills. It was said that he could fix anything. He worked at various mills, and when he was not at work, he installed many of the first electrical line connections to houses in the area. The couple also earned money by using their home as a boarding house for Slovak mill workers. Johanna cooked for them and laundered their grimy clothes.

The Kovanič couple became a Slovak-American family when Felix Jr. was born in August, 1916. He was followed by Albert, my father, in December of 1919, and their only daughter, Irene, in November 1922. The family lived a simple lifestyle rooted in a deep faith in God’s goodness.

In 1917, Felix filed a U.S. Department of Labor Declaration of Intent, the first step to becoming an American citizen. The declaration stated, “It is my bona fide intention to renounce forever all allegiance and fidelity to any prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, and particularly to Charles, Emperor of Austria, and Apostolic King of Hungary.”

When the war in Europe ended in November 1918, the new nation of Czechoslovakia was born from the ashes of Austria-Hungary. Czechs and Slovaks could finally live under their own government after being ruled by others for centuries. Some Slovaks living in America chose to return to their homeland, but Felix and Johanna stayed in America. On March 16, 1922, a Certificate of Naturalization was issued for four new American citizens: Felix Kovanic, his wife ‘Jennie’, and their sons.

In the following years, the American family name became ‘Kovanis’ instead of ‘Kovanič’. The reason for the change is now unknown. Perhaps it was not wise to be associated with the defeated Austro-Hungarians. These years were filled with happy times but also challenges brought about by the great economic depression that hit the US in 1929. Despite the hard times, Felix was able to always find work and to provide for his family.

Over in Europe, life was far from rosy. Johanna’s father and one of her brothers died during the war. Her mother was not faring well, and on top of it all, Johanna received a sad letter. In it, she discovered that the financial situation was unbearable, it was necessary to sell the family home, and would Johanna agree to sell it? Her share of the inheritance would be protected. Just like that, the sale happened. The family home was gone.

Moreover, the air on the old continent was once again thick with a threat of looming war. When the Second World War broke out and the US finally entered the conflict, Albert Kovanis enlisted in the US Army in the Field Artillery Branch. He was deployed to Hawaii where he was having a great time, sharing his stories in regular letters that he sent to his parents. But two days after his 22nd birthday party, the paradise turned to a living hell. On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked. Many American lives were lost, and Johanna prayed again for the safety of her son. A neighboring family in Carnegie received a government letter informing them that their son was killed on one of the attacked battleships. No letter was received from Albert after the attack, and Johanna was sick with worry. I cannot imagine the relief she felt when a note from her son arrived. Maybe it was Johanna’s prayers that carried the family through the war.

Felix and Johanna celebrated their Golden Wedding Anniversary in August 1965. It wasn’t long afterward that Felix suffered a stroke. He survived, but was left unable to speak and lost most of his ability to move. Johanna lovingly cared for him even though Felix no longer recognized who she was. My father would occasionally bring my grandparents to our house for a visit. They sat together in silence on our couch with Johanna holding Felix’s hand. She talked softly to him in Slovak and gently wiped his forehead with her handkerchief. Felix had a second stroke in August 1968 that completed the journey of his life.

Felix was buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery with an adjacent plot reserved for his wife. We worried that grandmother might want to join her husband in the afterlife soon, but she stayed with us for another 26 years and graced us with much joy.

In the years after Felix’s death, Johanna continued to live in her own house and was always surrounded by her family. Her daughter and grandchildren lived with her and took great care of her. In return, Johanna cooked, baked, and cleaned for the household. Felix Jr. lived nearby and visited often with his family. When Albert moved with nine of his children to Florida in 1971, Johanna was able to escape the cold of the north’s winter by going to Florida.

Although she was no longer a young woman, my grandmother’s spirit for adventure was still strong. There were stories of her first solo plane journey, her first ride on a motorcycle, or the time she went into the swimming pool with her grandkids.

A special event for Johanna was the ordination of my youngest brother Joel as a priest for the Diocese of St. Petersburg, Florida. As Joel was finishing his training, she proudly exclaimed, “We have a priest!” But Grandma did not live to see Joel celebrate his first mass. She passed three months before his ordination. In March 1994, she lay down in her own bed in the house that she had shared for many years with Felix, and closed her eyes forever.

After Johanna died, there were many unanswered questions about the family history. I thought that we would never learn the answers. But I began to remember what Johanna said after she came to America. “I never saw my mother and father again. I never saw my brothers!” I felt called to do something, to do what she could no longer do. There had been no contact with the family in Gbely since the late 1940s. News from Felix’s family in Vienna was even scarcer. What could be done? To our great fortune, I discovered Helene Cincebeaux. She and her mother led tours to Slovakia for Americans with Slovak heritage.

Helene agreed to make a side trip to Gbely during her next trip to Slovakia. She drove to this unfamiliar village with two clues. She was looking for anyone with a family name of Kovárik, and she had a photocopied sheet of some old black and white family photos. A villager directed her to a house where she was greeted by a gentleman who identified himself as Stefan Kovárik. He would turn out to be the grandson of one of Johanna’s brothers. When Stefan looked at the photos, he identified himself as the young boy who was posed with several adults including Johanna’s mother. A family reunion was in the making.

In the summer of 1997, a group of about 20 Kovanis family and friends made the trip to Gbely, Slovakia. The Kovárik family was physically reunited in that moment and emotionally reunited forever. A great celebration was held with photos, stories and slivovica flowing in abundance.

We were told amazing stories about the remote family past, older than anything we could have imagined finding out about. I was given a small replica axe and told that the great Austrian Empress, Maria Theresia, gave our Kovárik ancestor a sizeable grant of land near the village. The grant of land was reward for his skillful service as the royal executioner! Unfortunately, the land was lost when it was collectivized during communism.

Johanna’s brother Stefan was part of the conscripted Hungarian troops guarding Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austrian throne, when he was assassinated in Sarajevo in the run up to the First World War. As punishment, the troops were lined up and told to count to ten. Each 10th soldier would be shot. Stefan unluckily drew the number ten but was spared when a fellow villager and friend falsely swore under oath that Stefan was on sick call that day. In thanks, the home of the friend’s family had been preserved, and was turned into a museum in the village. It was the very spot where our family meeting was taking place. We have made several trips to Slovakia since.

After hiding and knowing little of my Slovak heritage in my youth, I now embrace it. My family and I have reclaimed past connections to our ancestral roots. We feel the love that reminds us of our Slovak heritage.

At our first meeting in Gbely, one of my relatives pointed to the ground and in a proud voice said to me, “This is your home!” It is my home indeed, and I can see the smiles on my grandparents’ faces as I celebrate belonging there.

Apple Strudel

Dough:

2 eggs

½ cup (100 g) Crisco

½ stick butter

4 cups flour

1 tsp sugar

1 tsp salt

½ cup warm water

Filling:

4 lbs apples

1 cup sugar

2 tsp cinnamon

½ cup golden raisins

½ cup chopped walnuts

Flour

½ cup melted butter

½ cup plain breadcrumbs

Combine all the dough ingredients in a large bowl. Knead the dough until it is soft, but not sticky. Cover it and let it stand 1 hour, in a warm place.

Peel, core, and cut the apples into thin slices. In a large bowl, mix the slices with the sugar and cinnamon. Add the raisins and walnuts, then set the bowl aside.

Preheat the oven to 375°F (190°C) and line a baking sheet with parchment paper.

On the counter, spread out a thin kitchen towel, preferably with a pattern (to help you see the shape of the dough). Sprinkle it with flour.

Cut the dough into four pieces. On top of the towel, roll out one piece as thin as possible, into a rectangular shape, with a long side closest to you. Stretch the dough without tearing it.

Brush the dough with the melted butter.

Spread the breadcrumbs over the dough (to absorb some of the butter), leaving a 2” margin along the top and bottom (long edges) of the dough.

Use a slotted spoon to scoop ¼ of the apple filling out of its accumulated liquid, and spread the filling on top of the breadcrumbs, maintaining the 2” margins.

Fold the 2” margins onto the filling, then roll up the strudel from the short side, using the towel to help you roll. Tuck the ends underneath.

Carefully transfer the strudel to the prepared baking sheet, seam side down. Brush with a small amount of melted butter.

Repeat steps 5-10 for the remaining three pieces of dough.

Bake about 45 minutes, until the strudel is lightly golden on top.

Remove from the oven and allow to cool.

Cut into 1” slices and serve.