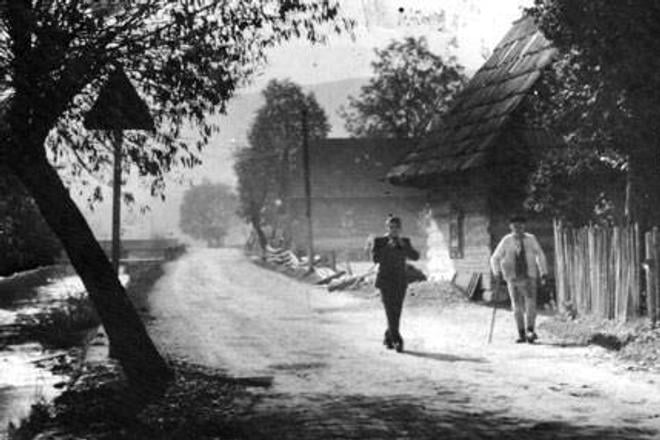

In a small village in Zemplín County in the 1890s, something extraordinary was happening. More than 1,100 residents were receiving an average of 35,000 crowns a year from relatives working in American steel mills and mines — the equivalent of around $250,000 in today’s money, according to some estimates. This was no act of charity; it marked the beginning of a financial revolution that would transform the Slovak countryside.

More than money

By 1910, Slovak emigrants in America were earning $219 million annually, remitting an estimated 100 million crowns ($20 million) to their homeland each year — a sum that would reshape the nation.

But the true revolution lay not only in the figures. It was in how this “American money” fundamentally altered Slovak society — and what lessons the present can draw from the past.

This influx of capital enabled Slovak farmers to buy land from the aristocracy for the first time. Property prices rose, power dynamics shifted, and the very foundations of society began to change.

The funds sent home were not only used to acquire land and farming equipment. They also financed churches, schools, monuments and political movements. For the vast majority, improving basic living conditions was a priority, but the impact went deeper: a social transformation was under way.

The story of Michal Bosák illustrates this momentous trend. A Slovak banker whose signature appeared on American banknotes, Bosák funded a school in his native village on one condition: no pub could be built nearby. He also financed what is still regarded as one of the most beautiful buildings in Prešov — the Art Nouveau Bosák Bank. Like many Slovaks in America, he felt a duty to give back to the homeland.

The modern opportunity

As Slovakia begins to recognise the potential of its historic diaspora, particularly in the United States, an obvious question arises: could this be an opportunity for a country long troubled by brain drain?

By some estimates, as many as two million descendants of Slovaks live in the US alone, many eager to contribute to their ancestral homeland — whether through building monuments, restoring landmarks or supporting schools in the villages their forebears left behind.

This is not only about financial capital, though that presents a huge opportunity, especially in eastern Slovakia where American investment could have a transformative effect. It is also about know-how, values, skills and networks — assets Slovakia could harness to its benefit.

Countries such as Ireland, Israel and India have successfully leveraged their diasporas through investment funds, knowledge-transfer schemes and structured engagement strategies.

The question is not whether Slovaks abroad can contribute to their homeland’s development — history has proved they can and will. The question is whether Slovakia will create the frameworks to harness their capital, expertise and connections for the next chapter of national progress.

The real question is whether Slovakia is ready.