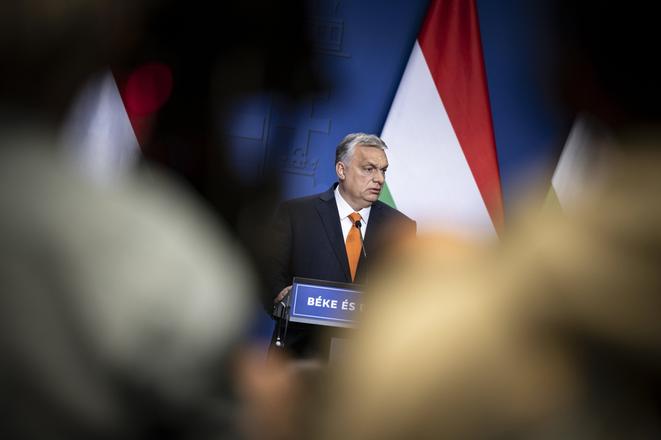

While Slovakia and the Czech Republic have seen several changes of prime minister in recent years, Hungary chose on Sunday to keep the same one it has had since 2010. Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party won another crushing victory, their fourth in a row, in parliamentary elections across Hungary on April 3.

Orbán thus gets a fourth consecutive term in office, his fifth overall, as Hungarian prime minister. Fidesz’s position is even stronger than in the outgoing parliament, with the party gaining two more seats and retaining its constitutional majority.

“We have scored a victory so big that it can be seen even from the Moon – but definitely from Brussels,” Orbán, who has often found himself at odds with the European Commission, said in his victory speech on Sunday night.

He was quick to enumerate his opponents: the left at home, the international left everywhere, bureaucrats in Brussels, all the funds and organisations of “the ruling empire”, the foreign media, and even Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

Having previously lauded his warm relations with Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, Orbán pivoted to campaign on a promise not to let Hungary be dragged into the war in Ukraine, and refused to supply Ukraine with weapons – or even to allow weapons to be transported through Hungarian territory to Ukraine. He accused the opposition, without evidence, of wanting to drag Hungary into the war.

Observers noted that, in terms of his attitude towards Ukraine, Orbán is isolated within the Visegrad Group (V4), which unites Slovakia, Czechia, Poland and Hungary. Unless he changes this approach, cooperation within the Visegrad Group will likely be reduced to a minimum, say observers.

The gradual chilling of relations

Representatives of other V4 countries will tend to distance themselves from the political leadership of Hungary or will prefer to cooperate in different spheres, opined Pavlína Janebová, research director of the Association for International Affairs in the Czech Republic.

“This does not mean the immediate break-up of the Visegrad Group; cooperation will probably continue at lower levels, but it may chill gradually,” she told The Slovak Spectator. “What we currently see at the political level can be called a crucial crisis in the history of the V4.”