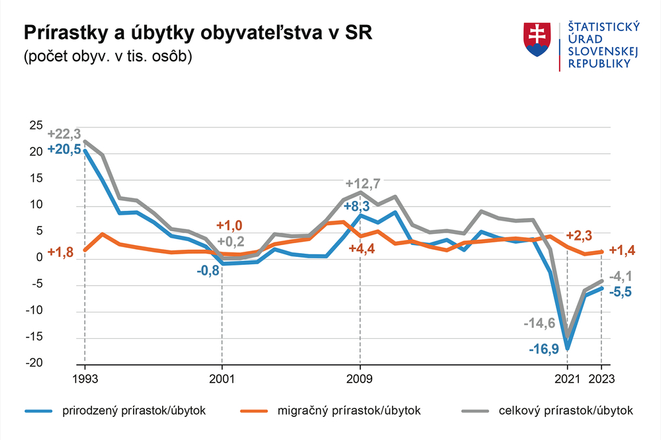

Slovakia’s population has been shrinking for the third year in a row. Despite this, the country’s governments have remained rather hostile to the idea of welcoming more foreigners from outside the EU.

The Statistics Office has published the latest numbers that show a year-on-year decline in the number of citizens by more than 4,000 people.

Slovakia had 5,424,687 inhabitants at the end of 2023.

The Office underscores that the population had been growing for 75 years before it began to shrink three years ago. The data show that the Slovak population has increased by a mere 88,200 people since the emergence of Slovakia in 1993.

The decrease in the total number of inhabitants in 2023 was mainly influenced by the natural decline of the population, the Office writes in its report.

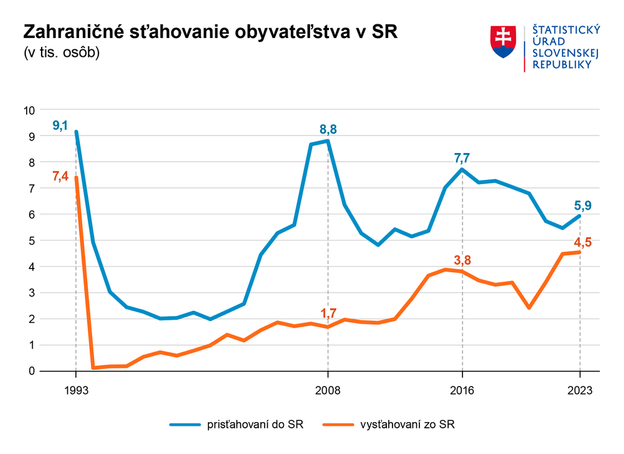

Immigration, despite showing encouraging numbers, didn’t help reverse the latest trend due to a rising number of people leaving the country.

Fewer babies

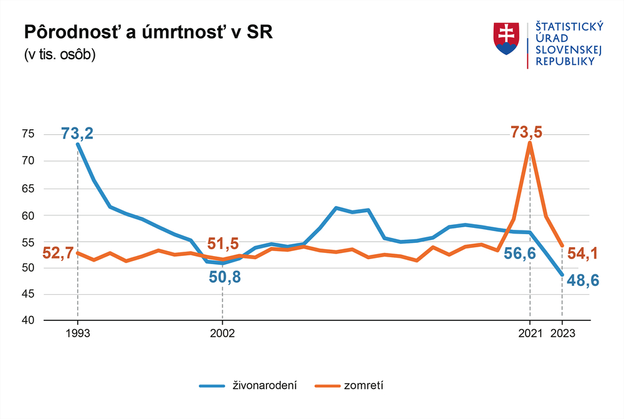

Last year, more than 54,100 people died. As many as 48,600 children were born in the country. As a result, a population decline of 5,500 occurred. This situation has been observed for four years now, in part due to the coronavirus years of 2020-2022.

“However, the natural population decline in Slovakia continued in 2023, despite the fact that the mortality rate reached the long-term average after three pandemic years,” said the Statistics Office’s Population Statistics Department Director Zuzana Podmanická. She went on to cite the fact that the number of children born in Slovakia fell significantly below 50,000 in the past two years.

However, the declining birth rate has been observed for six years.

In the early nineties, the number of births began to fall - from more than 70,000 to exceeding 51,000 in 2002. Then, the number began rising again. In 2011, there were 61,000 newly-born babies. But the figure fell slightly again, and more visibly in the past two years.

The decline in the historically lowest value is also confirmed by the gross birth rate. “The gross birth rate in Slovakia reached an unprecedentedly low value in 2023, not only in the modern history of independent Slovakia, but in the last 100 years,” explained Podmanická. During the last 20 years, this indicator reached the value of 1,033 births per 100,000 inhabitants. It fell below 1,000 in 2022. Last year it dropped even deeper, to 896 newborn children per 100,000 inhabitants.

But births and deaths aren’t the only factor that has had an impact on the total number of inhabitants in Slovakia.

More people move in than out

Migration is the other factor.

The population increase through migration has been in positive numbers for a long time, the Statistics Office reports. For example, 5,923 people relocated to Slovakia last year and have permanent residence in the country. And 4,522 people decided to move out of the country.

Many of those who moved to Slovakia last year came from Czechia (1,542), Ukraine (523), Austria (519), Great Britain (579), Germany (368) and Hungary (326). Conversely, those who decided to emigrate from Slovakia left for Czechia (1,876), Austria (781), Germany (372) and Great Britain (376) in 2023.

Also, according to the latest census, 58,498 foreigners with permanent residence lived in Slovakia in 2021. The number almost doubled in a decade.

The number of immigrants has exceeded the number of those who emigrated every year, ranging from 900 to 7,100 people, the Office points out. Last year’s migration balance stood at 1,401 individuals.

But in the last three years these figures haven’t been able to compensate for the losses resulting from the falling birth rate.

European Migration and Asylum Pact approved

The Statistics Office, headed by former Smer MP Martin Nemky as of early February, published the latest demography data when on Wednesday the European Parliament adopted 10 different laws reforming the EU’s migration and asylum policy. They’re yet to be approved - formally - by the Council. The package will come into force in two years.

Slovakia rejected the draft of the so-called new “Migration Pact” by voting at the level of ambassadors to the EU in Brussels in February, the Slovak Foreign Ministry stressed. However, it will also apply to Slovakia.

The new system is based on solidarity, which means that Slovakia can choose if it will take in asylum applicants, contribute financially or provide technical support in tackling migratory pressures on other EU member states. Yet, the Slovak Foreign Ministry repeated on Thursday that it does not agree with the approved changes, saying that it refuses to accept the condition of the mandatory admission of illegal migrants to Slovakia.

“Illegal migration is a huge challenge facing the EU, and it's our duty to tackle it above all in line with the sovereign interests of our homeland,” said Slovak Foreign Minister Juraj Blanár of the Smer party.

The intake of immigrants is, however, optional.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, almost 140,000 Ukrainian newcomers have found temporary refuge in Slovakia. However, at the same time, the country approved only 37 of 416 asylum applications in 2023, an approach adopted by the authorities a long time ago.

What the MEPs approved on Wednesday is something that Fico’s government called for in 2016, when the EU faced the first wave of a migration crisis. Fico then opposed mandatory quotas for immigrants.

“If we don’t want to accept migrants, and we don’t, then we can send more police officers, provide more funds, more experts,” Fico said back in the day.

Today, it seems clear which path of ‘mandatory solidarity’ Fico will choose. He will prefer to make financial contributions instead of allow migrants into Slovakia, though they could help Slovakia’s demography and economy.

“The European Union should say outright that illegal migration is mainly motivated by economic motives. And it's not only a problem, but also an opportunity,” economist Vladimír Baláž said last year. “Europe is aging fast. And the eastern region in particular. Our employers are already having trouble finding manpower.”

Recently, the country has decided to issue more visas for workers coming from certain countries. This change only concerns certain industries. But like many Slovak politicians, many Slovak people are suspicious of foreigners and do not trust them.

The economist added that Slovakia will have to learn how to integrate foreigners.

“The sooner, the better,” he said.

Population increase and decrease in Slovakia (in thousands): blue (natural), orange (migration), and gray (total). (source: Statistics Office)

Population increase and decrease in Slovakia (in thousands): blue (natural), orange (migration), and gray (total). (source: Statistics Office)

Births and deaths in Slovakia (in thousands). (source: Statistics Office)

Births and deaths in Slovakia (in thousands). (source: Statistics Office)

Migration (in thousands): blue (immigration) and orange (emigration). (source: Statistics Office)

Migration (in thousands): blue (immigration) and orange (emigration). (source: Statistics Office)