A glossary of words is also published online.

Eight years have now passed since history teacher Juraj Smatana published his list of dozens of mostly copycat Slovak and Czech websites that suddenly popped up and started spreading pro-Kremlin propaganda amid the 2013-14 Euromaidan protests in Ukraine.

“The narratives are the same: the corrupt, lame-duck West and fascist Ukraine again want to attack the strong and resource-rich Russia, run by the great leader [Vladimir] Putin; Slovakia is seriously threatened by the decaying West and its homosexuality, immigrants and terrorists, which may be prevented only by leaving Western structures; it is important to abolish sanctions against Russia,” Smatana who is now an MP for OĽaNO, the largest party in the governing coalition, told The Slovak Spectator back then. “As these claims are in stark contrast to reality, the supporters of these opinions have drawn closer, sharpening the borders between them and other people.”

Despite warnings from activists and from the Slovak Information Service (SIS), the country's main intelligence service, Slovak governments – led at that time by the Smer party – did little or nothing to deal with these disinformation websites.

The situation changed with outbreak of the pandemic in 2020, when the current government launched several projects to debunk Covid-related disinformation and the police started knocking on the doors of the people who were most active in spreading them.

Now with the Russian invasion of Ukraine giving rise to yet more disinformation, the Slovak government is going even further. Last Friday, the cabinet and the parliament hastily passed an amendment to the Cyber Security Act allowing the National Security Authority (NBÚ) to shut down sources of “malicious content”. This means software or data that causes cyber security incidents, fraud, theft of data, serious misinformation and other forms of hybrid threats.

“This is a democratic country, there are some laws here, and if someone breaks them, they have to pay for it,” Defence Minister Jaroslav Naď told the Sme daily. “No matter that they label themselves 'journalists': we know that they are serving the interests of foreign powers.”

Disinformation on public-service television

A case in point, illustrating the influence of Russian propaganda in Slovakia, is a recent incident involving the public-service television broadcaster, RTVS. Right after Russian forces moved into Donetsk on February 22, RTVS aired comments by former prime minister (1991-92) and justice minister (1998-2002) Ján Čarnogurský, who is well-known for supporting Vladimir Putin’s regime and spreading Ukraine-related disinformation.

He has defended Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea with pro-Kremlin talking points, saying that Crimea was just being "returned" to Russia.

New legislation

Mária Kolíková (SaS), the minister of justice, has proposed an amendment to the Criminal Code that would, controversially, sanction the spreading of misinformation – even by accident. Anyone convicted could face up to a year in prison.

Several coalition leaders have questioned this paragraph, calling it vague and fearing that it could be used to punish people for expressing an opinion.

Minister of Culture Natália Milanová (OĽaNO) has presented legislative changes to regulate media that operate only on the internet. Currently, the standard obligations of publishers do not apply to them. The law is due to be debated by parliament in March.

Since December 2020, the European Union has been debating a draft Digital Services Act which would address the rules for online platforms such as social networks, online shops, accommodation services and more.

He has also stated that Crimeans wanted to be part of Russia partly because of the so-called "Korsun pogrom". This is a reference to the purported deaths of residents of Crimea at the hands of Ukraininan extremists as they were returning home after attending the Euromaidan protests in 2014. The story was supposedly documented, and then widely promoted, by the Kremlin. However, despite investigations, including some by human rights groups, no evidence has ever emerged that any killings actually took place. Certainly, no verifiable victims' names, nor graves, have ever been identified.

Following a wave of criticism, Vahram Chuguryan, head of the RTVS news section, stepped down the day after the interview with Čarnogurský was aired.

“The newsroom management, led by Vahram Chuguryan, has long been pushing the theory that objectivity means publishing every opinion, and therefore also obvious lies,” the chairman of the parliamentary culture and media committee, Kristián Čekovský (OĽaNO), told the press. “He balances the truth with nonsense.”

Russian propaganda in Slovakia

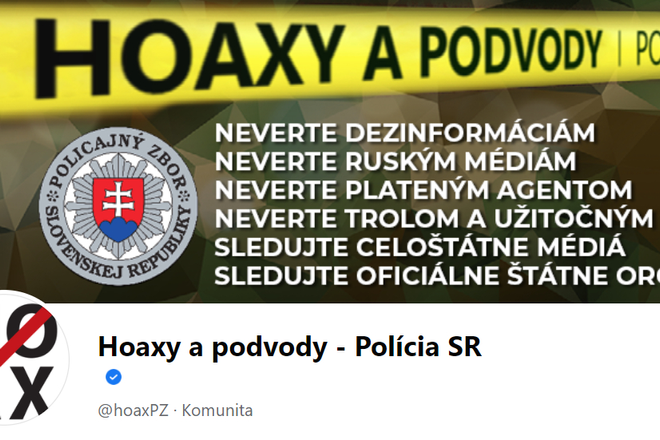

In connection with the invasion of Ukraine the disinformation war continues as the Russian Federation is trying to influence the perception of reality among the citizens of the Slovak Republic, the Slovak police stated on a special Facebook page that they have set up to combat disinformation.

The police page also maintains a list of pro-Kremlin accounts which “spread misinformation, manipulate and lie.” Some of these accounts publish as many as 200 posts a day.

In the recent disinformation effort, some people have received fake text messages pretending to be official government orders declaring that every man aged 18-60 is obliged to join the armed forces.

There is also a video being circulated that purports to show people in Kyiv running towards the camera. Its description says that the recording proves that fighting in the streets of the Ukrainian capital is a lie. However, the video was recorded in 2013 in Birmingham, England, during the filming of a scene for a zombie movie.

The police have warned citizens that its National Criminal Agency (NAKA) is searching for such crimes on the internet in connection with the war in Ukraine. The propagation of war is a crime in Slovakia, punishable by 10 to 25 years in prison.

One of the most serious crimes related to the current situation was a video recording of a man publicly threatening President Zuzana Čaputová, and claiming that he would personally execute her. Police officers identified the man and have searched his home. However, it was empty and they are still looking for him.

On February 26, several Slovak newsrooms that have reported on the hybrid war, among them the Refresher news website, the Denník N daily and the news website Aktuality.sk, came under cyber attack. Hackers also attacked the Czech newsrooms of iDnes and public-service broadcaster Czech Television, Refresher reported.

How public opinion towards Russia has changed

The Slovak population has consistently been judged by researchers as particularly vulnerable to pro-Kremlin propaganda and disinformation.

Data from Globsec, a security think tank, has shown that 50 percent of Slovaks are inclined to see Russia as a victim of the West and in one poll 56 percent of respondents supported the claim that NATO deliberately provokes Russia by encircling it with military bases.

A poll by the Focus agency in January 2022 found that 44.1 percent of respondents believed the US and NATO were to blame for tension between Ukraine and Russia, while 34.7 percent said that Russia was the cause of the tension.

A day after the Russian invasion, the AKO agency conducted a poll that showed that more than 62 percent of respondents said Russia was responsible for the war. Meanwhile 25 percent of those polled believe the US should be blamed for the conflict.

Meanwhile, the national administrator of web domains in the Czech Republic, CZ.NIC, shut down several Czech disinformation websites that had been spreading fake, Russian-origin reports about Ukrainian "atrocities" and using these to justify President Putin's decision to invade Ukraine.

Further plans

Even before the Ukraine crisis, Slovakia's Ministries of Justice and Culture proposed making several changes to the Criminal Code and media laws in order to address problems with misinformation.

Also, the Interior Ministry has started to build a Centre for Combating Hybrid Threats, which will eventually employ about 50 people. This will analyse disinformation and design strategies to defend the country against it.

The Ministry of Defence is also planning to conduct its own campaigns to strengthen public resilience against foreign information operations.

"The debunking of hoaxes is a small but important part of the communication effort aimed at combating misinformation," Martina Kovaľ Kakaščíková, spokeswoman for the Ministry of Defence, told The Slovak Spectator.

Matej Spišák from the non-governmental project Infosecurity.sk, which debunks disinformation on social networks, applauded these efforts by the government. Although the changes are coming rather late, Spišák noted, this is understandable because the current Slovak government had to face the pandemic crisis as soon as it came to power and the Ukraine crisis has only recently emerged.

"The ministries were aware of the hybrid threats, they were ready for their arrival, but they did not yet have the capacity to deal with them properly," Spišák told The Slovak Spectator.

The Spectator College is a programme designed to support the study and teaching of English in Slovakia, as well as to inspire interest in important public issues among young people.

The official police Facebook page battling misinformation (source: Facebook/Slovak Police )

The official police Facebook page battling misinformation (source: Facebook/Slovak Police )