THE WAY the world media bid farewell to Umberto Eco, showed us little Slovaks burdened with the hate towards people educated in humanities, what intellectuals and artists are good for.

That does not mean that every teacher, writer, and graphic designer will have the right for the same kind of ovations after death, nor that we are all equally talented. But it does paint a certain comprehensible picture of what the mission of an educated person is and what the humanities are about.

Intelligentsia and parasites

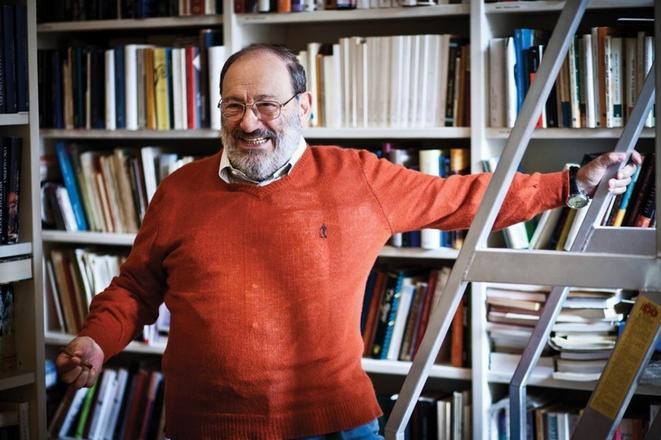

At the time when Nobel Prize laureates were saying goodbye to the Italian lover of comics, occult literature, blasphemist, pamphletist, and author of a postmodern novel that raises its own reader, Slovakia was shaking with a new wave of hatred towards teachers.

As I was reading the obscenities and primitivisms that were addressed to them, accusations that they’ve got three months of holidays, that they are doing nothing, that they teach four hours a day, that they should go work in a factory to see what real work is like; I remembered once again (like I did during the strike of medical doctors) the testimonies from the 1950s about humiliation of those who were educated, and the times when intellectuals were divided into the “working intelligentsia” and the parasites.

The emancipation of the inhabitants of the onetime upper Hungary started thanks to poets, theologians, writers, and we like to label ourselves the country of Proglas and the Word, which we decorate with some ethnic-magical qualities in the chauvinist pathos. Despite that, in reality we are unable to understand and appreciate the creative activity and mission of humanities.

At best we consider them a romantic pendant of a so-called real, exact science, which measures, calculates, renders, and researches; at worst a way for lazy people to be able to pretend they’re working.

Part of the public does not connect things like literary research, or art exhibitions, with work, but rather with some more or less well-made excuse of those who despite uranium mines in Jáchymov, concentration camps, and gulags, continue suffering from a “mental disorder” that makes them believe their lack of exact thinking and their doubts are a full-fledged activity for adult people.

Eco was exceptional

It is hard to understand the self-confidence that the fools display when commenting on the experimental broadcasting of radio Devin, or an exhibition of conceptual art. Who could say they haven’t heard people utter in an art gallery that “my daughter could have done that as well” or in the theatre about an actress “she looks like a whore, we should have gone to see something else”.

On the day when even the big Slovak dailies ran the pictures of the heretic semiotic on their front pages, I almost felt ashamed.

A photograph of a writer on the front page is a hard-to-understand provocation in a country where art gets no considerable attention; where important shows, compositions, and books emerge not thanks to, but despite the atmosphere in the society; where a regional governor dares to label a public theatre performance “pervert”; where programmes about art are doomed to be broadcast only after 10 pm (with the exception of public-service radio and television), because it is only logical that lazy intellectuals do not work during the day and can thus wait till night for the performing part of the population to finish watching their demented TV series.

In truth, Eco was not just any intellectual hated by the local pub in Klenovec; he was a professor, that’s something like a medical doctor, he liked the booze, he liked eating and drinking, he was, how to put it, our man. He simply did well, unlike that snob Visconti, in mingling with us; now and then he seemed like a well-meaning old fellow who gives a free merry-go-round ride to you and your girlfriend at the fair.

There was no mannerism, as we imagine it, in him, he simply wasn’t an affected queer that we see at exhibition openings and fashion shows. As a specialist on meaning and symbols, Eco managed to navigate through all strata of the Italian society.

And now for that unfortunate thing. Where did we get it from, who taught us to hate the educated people so much, to call them impractical, barely in their right mind, unable to work even as a warehouseman in a Chinese heroin warehouse therefore forced to be occupied with transitive verbs in English poetry in the second half of the 17th century?

What on earth is that job that those people do, what do they do when they come to their office, to their research institute for researching words and languages, or design, or lace, or Flemish art, or the influence of porn on lowering the nuclear tension in the world?

And we’ve got the answers. The internet raff know that these losers belong to gas chambers, to factories, to jail – because they’re frauds like Toufar, or drug addicts like Baudelaire, even though they don’t know him, but if they happened to read him by chance, they would say that even their turtle could write such nonsense as well.

Hate and mistrust

At higher levels, hate turns into mistrust. The dispute over the character of the research at the Slovak Academy of Sciences has for years circled around the question of how to turn humanities into something that could be used, for instance, in the automotive industry. They could for instance proofread the manuals for the installation of a ski rack on a car roof; or, in case they harbour more creative ambitions, they could even create funny bumper stickers.

Even the scientific community is not clear about why we should have any sociologists and political scientists at all when we are missing turners and braziers.

It could look like a class war for money, but Slovakia is too small for us to be able to afford cultivating hate towards educated people. Thanks to them this country exists, they invented it in the past, they filled it with certain content, they attempted to make it exceptional, even though they terribly failed to do the latter.

There is nothing we need now and in the future more than humanities. Thanks to them we understand why we are here of all places, why we do what we do, what the generations before us were doing, how we will or won’t be able to keep up their work, how much we are able to move our abstract thinking further than the idea of sex with the girl next door.

Developing humanities-style thinking and our cognitive abilities is the best testimony about the state of the society. Thanks to poets we know how Greeks and Vikings and Romans and Slavs lived; thanks to literature we know about the development of ethics, morals, and mainly language.

The lack of ability to appreciate the work of educated people is the underestimated despicable quality of Slovakia that holds us back more than the lack or the excess of capital and investments.

Michal Havran is a theologian, editor-in-chief of jetotak.sk. This opinion piece was first published in the Sme daily on March 3.

Umberto Eco, the Italian lover of comics, blasphemist, pamphletist, and author of a postmodern novel that raises its own reader. (source: PROFIMEDIA)

Umberto Eco, the Italian lover of comics, blasphemist, pamphletist, and author of a postmodern novel that raises its own reader. (source: PROFIMEDIA)