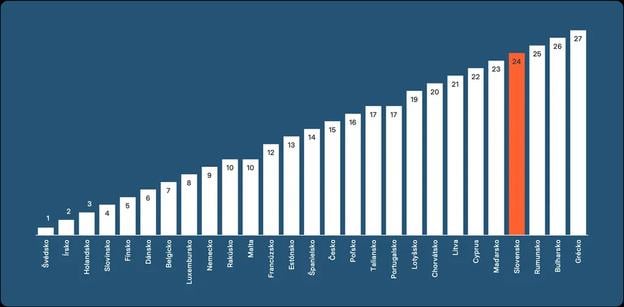

Slovakia’s economy is losing steam. Once a regional growth leader, the country now ranks among the poorest performers in the European Union, coming 24th out of 27 in a new Prosperity Index compiled by Slovenská and Česká sporiteľňa banks. Only Greece, Romania and Bulgaria fared worse.

In contrast, neighbouring Czechia ranked 15th and Slovenia 4th. The top three positions went to Sweden, Ireland and the Netherlands.

The slowdown is not just a symptom of wider European stagnation. Analysts say Slovakia’s long-standing model – a small, open economy built on cheap labour and foreign investment – is hitting its limits. “It appears that our economic model is running out of steam,” said Mária Valachyová, chief economist at Slovenská sporiteľňa.

Modest growth, weak investment

From 2019 to 2024, Slovakia’s GDP grew by 8 percent, outpacing the EU average of 5 percent. But the comparison is misleading. Countries with similar export-driven models – like Poland, Romania and Bulgaria – grew by 15 percent over the same period. These countries offered a more balanced tax system, attracted new investment, or focused on more forward-looking sectors, Index magazine reports.

Slovakia’s household consumption helped boost growth, but at the cost of savings. Slovaks save less than 6 percent of their income, compared to 14.5 percent across the EU. And their investments tend to stay in cash or current accounts, missing out on long-term returns.

Household consumption in Slovakia has been declining in recent months, according to data from the Economic Sentiment Indicator published by the Statistics Office. In May, the index recorded its sharpest drop in 19 months.

Meanwhile, foreign investment has slowed dramatically. Slovakia lags behind its regional peers in attracting new investors and launching modern projects. Investment growth has been stagnant, rising just 10 percent in five years – compared to 30–40 percent in neighbouring countries.

Risk of falling further behind

The country’s heavy reliance on foreign trade – exports and imports amount to 170 percent of GDP – makes it particularly vulnerable to global tensions. Potential US tariffs on cars could hit both Slovak exports and its EU partners.

Adding to the pressure, businesses cite a lack of skilled workers, unpredictable energy prices and a burdensome regulatory environment. Corporate income tax has risen to 24 percent for large firms, among the highest in the region, while a new transaction tax has increased compliance costs.

Slovakia also trails in attracting skilled foreign workers, issuing just 24 EU Blue Cards last year – compared to 505 in Czechia and 7,400 in Poland.

Structural challenges

High industrial energy costs and growing labour expenses are eroding competitiveness. Labour costs have now overtaken those in Czechia. And unlike countries like Spain or Portugal – where wages are similar but job markets are more flexible – Slovakia lacks geographic advantages or an active migration policy to compensate.

Spending on research and development is also low, just 1 percent of GDP, well below the EU average. The number of start-ups per capita is one of the lowest in the bloc.

Unless Slovakia reforms its business environment, improves talent attraction and shifts to higher-value sectors, economists warn it risks sliding further behind. “Without clear, predictable policies and a skilled workforce, Slovakia won’t remain attractive to investors,” said Michal Horváth, chief economist at the National Bank of Slovakia.

Assembly of Kia vehicles at the Kia Slovakia plant in Teplička nad Váhom, near Žilina. (source: TASR)

Assembly of Kia vehicles at the Kia Slovakia plant in Teplička nad Váhom, near Žilina. (source: TASR)

2025 Prosperity Index (source: Slovenská sporiteľňa)

2025 Prosperity Index (source: Slovenská sporiteľňa)