While admitting that the current situation is difficult, they are already seeing the first signs of recovery in the real estate sector and believe that good times for developers and investors will return. They also say that the financial markets are recovering in certain parts of Europe and hope that lending will improve in Slovakia too: the question is when. Leading real estate consultants agree that it is the banks that need to grease the wheels and provide funds to make real estate attractive again for purchasers and the industry. The Slovak Spectator spoke to Andrew Thompson, managing partner of Cushman & Wakefield, Jörg Kreindl, managing director of CB Richard Ellis and Peter Nitschneider, Associate Director and Head of Investment and Professional Services at King Sturge, about the pains and the prospects of the real estate market in Slovakia.

The Slovak Spectator (TSS): Sceptics say that the golden times of real estate are over in Slovakia while optimists say they have detected some signs of revival. How do you assess the current situation?

Andrew Thompson (AT): My position is somewhat positive. The golden times may refer somewhat to the availability of debt financing. I have to say that lending markets are already coming back in places like the UK and I am aware of some banks a lending for development projects in Slovakia too. I can see positive signals such as GDP growth expectations in Slovakia and elsewhere, talk of recoveries, etc. I do expect the bounce-back to be relatively quick.

Jörg Kreindl (JK): It always depends on one’s perspective. As a building occupant the opportunities are endless these days – fantastic deals wherever one looks. This window of opportunity will continue in some segments for a longer period and in others for a shorter while. The good times for developers and investors will return as well – the question is when. Once the existing stock is about absorbed and demand is healthy again, the developers will start to be active once again and international investors will buy their products. Of course, the banks need to be back to normal by then – without financing there are no golden times.

Peter Nitschneider (PN): We are in a very difficult situation. The last institutional investment transaction happened in the third quarter of 2008. Since then nearly all of the investors are just observing the market or restructuring their portfolios. The first signs of recovery are vivid and, hopefully, during the next year we will see trading again. But definitely, at a different price level. Investors need to first saturate the lucrative markets in countries such as the UK, Germany and France, and then they will spread through the central and eastern European (CEE) region. The more eastern, the more time it will take.

TSS: Which segments of the market have been most affected by the global financial crisis and which are least affected? Which currently have the greatest potential for revival?

AT: All segments have slowed down but all have the potential to come back. My one reservation relates to high-end residential flats where I fear that there simply will not be the demand that was expected 2 or 3 years ago.

JK: The global financial downturn resulted in a global recession and inevitably all sectors of real estate got hit badly. The rest is very market and country specific. You could argue that Bratislava’s office market is the least affected one: it is still the most dynamic and developers will be able to sell their under-rented projects in the mid-term future. Then the vacancy rate will go down and rents will grow.

Industrial properties are struggling from a still declining demand from occupants and hardly any appetite from end-investors. This sector could come back quickly though, depending on whether the European industrial sector will continue to recover.

Retail in Slovakia hasn’t had the level of sophistication comparable to other countries in CEE and one should believe there is the most potential in retail: but the proximity to Austria and the expensive euro, or rather the inexpensive, good-quality shopping opportunities across Slovakia’s borders will make it difficult for retail here in the near to mid future. Residential will undoubtedly come back – it is a question of time and when people begin to trust the economy and their sustainable jobs again.

PN: It’s hard to say; all sectors were hit the same way, the difference was which sector was hit first. The investment and residential markets were hit first mainly due to lack of liquidity and inaccessibility of financing in the market. The commercial market (office, industrial) followed later due to the cuts in production. The retail market, directly linked with growing unemployment, was hit at the end.

TSS: What factors will play the most important role for the development of Slovakia’s real estate market in 2010?

AT: First, it is the availability and cost of financing. At the moment this is killing most development projects and potentially some investment acquisitions. The banks need to grease the wheels and provide some loans to make real estate attractive. Second, growth in the GDP would have several benefits – with everyone having more confidence in the economy (occupants, bankers, investors, developers). If tenants require space for expansion, developers become active and investors take confidence in the underlying sustainability of the markets. This should lead to employment growth – although next year it is expected that unemployment will peak at the same time that GDP growth reaches 2 to 3 percent, or 3.7 percent according to the IMF.

Third, it is consumer spending, related to the availability of income and financing and GDP growth but important for retailers seeking to expand – confidence will come back if consumer spending improves. Fourth, the stability of the Czech crown and the Hungarian forint at reasonable exchange rates – it helps to prevent goods from becoming cheaper in neighbouring countries and the flight of consumer spending to those countries.

JK: Slovakia has to return to the understanding that as a very small country it needs to undertake greater efforts than others to attract direct investment – in both the industrial and service sectors. For a few years this worked brilliantly. With the current government and the upcoming elections I am rather sceptical that we are going in the right direction. After all, real estate is stimulated by economic prosperity and only to a certain extent is it vice versa.

PN: Any project and any development in any segment will depend on the availability of funding – bank financing. Because the banks have been hit the most by the crisis, they now are financing only the “best” projects. They are picking off just the “cherries on the fancy cake”.

TSS: How has the global economic crisis changed the real estate consultancy business?

AT: First, it has changed the perception of developers that “every site is a development opportunity” into “we need to think whether this site will work, why it has a competitive advantage and why it will make money” so that we don’t get some of the poorer-thought-out developments in Slovakia. This will be better for occupants, citizens, communities and investors.

It has promoted more professionalism and analytical judgement. The question “what if...” for example, about risks needs to be considered more deeply. From developers and investors to banks and occupants – everyone needs to have a good think about what they are doing, who they decide to partner with and what the opportunities will be.

Second, it has “burst the bubble” of the idea that Slovakia is somehow insulated from global economic affairs. We are all inter-linked.

Occupants, banks and investors are now appreciating more the value of true high-quality property and asset management. In the good times, everyone can perform – everyone wants space, quality matters less. In tougher times, occupants start to suffer and this is made worse if the buildings are not managed correctly. This also goes together with developers building better, more sustainable products.

Third, occupants are now more respectful of the advice of professionals. Choosing real estate is considered one of the most complicated purchasing decisions. It sometimes takes a crisis for managers whose business is not property to understand the difference and value added between a professionally-advised deal and a “direct” deal. A simple example might be where developers provide misleading information on future service charges – sometimes providing figures which are some amount below what the actual costs really are.

Of course, all of this should encourage anyone looking to do something in commercial real estate to seek out professional advisors. At the same time, people purporting to provide professional advice who do not have the systems, ethics, professional capability and capacity to do a really professional job will find it more difficult to secure work and there will be a natural gravitation towards the more reputable people. Hopefully, the current situation has made everyone into more well-rounded professionals.

JK: The real estate consultancy business has a lot of different aspects: Global companies must cover a lot of different business lines in order to maintain a regular income in addition to the transactional business. Then they can survive. Plus many companies didn’t react quickly enough to the changing conditions. They will probably disappear soon.

Bratislava’s consultancy landscape is a good reference point to what has happened in commercial real estate: the number of people working in real estate consultancies has probably halved during the last 12 months.

PN: Definitely yes. The windows of opportunities have been recently re-opened and only those flexible and creative will adapt.

TSS: In the CEE region, most real estate investment flows to the capital cities and much less to the regions. What could make the regions more attractive to investors?

AT: In terms of attraction of investment it is better availability of information. In time, as these regional centres show their performance, they will be more easily priced in the measure of risk versus return. Then, better control and clearer planning approaches by city authorities would help. Some developers have expressed their disappointment to me that there are rather small towns that have granted several developers approval to build shopping centres. Clearly, this doesn’t make sense for anyone and adds more risk to everyone concerned. If no one then decides to go ahead (because of the risks of a competing centre being built next door), it is the consumer who loses out. There also appears to be too much “qualitative” assessment of development schemes which results in approvals being slowed down so much that projects suffer.

JK: In the case of Slovakia it certainly is infrastructure. I don’t see why eastern Slovakia should not become attractive for industrial and service businesses – if the obstacle of a missing highway was removed as well as having only one remaining flight operator. Generally speaking, the vast majority of real estate developments will always take place in larger cities. In the case of Slovakia, this is Bratislava – and, in very limited terms, Košice in the future.

PN: Western Europe has experienced re-pricing and therefore the investment market has picked up. In order to attract foreign investors into the CEE region, expectations need to be much more realistic.

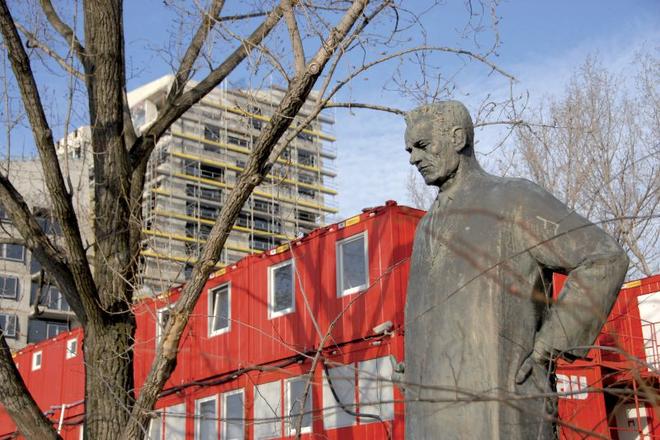

Celebrated Slovak architect Dušan Jurkovič looks on as another new building rises up next to him. (source: Jana Liptáková)

Celebrated Slovak architect Dušan Jurkovič looks on as another new building rises up next to him. (source: Jana Liptáková)