You can read this exclusive content thanks to the FALATH & PARTNERS law firm, which assists American people with Slovak roots in obtaining Slovak citizenship and reconnecting them with the land of their ancestors.

Among the tens of thousands of Slovaks who emigrated to America at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, was a woman from the village of Dlhé Klčovo, eastern Slovakia. One of her last wishes before she passed away was to be buried at home. Her descendants wanted to fulfil her wish, so they had her cremated and sent her ashes home in an urn.

However, something unexpected happened. When the urn arrived in the village, her family thought it was cocoa, and so they baked a cake.

"I read this story in newspapers," says historian Martin Javor during a tour of Kasigarda, a museum of emigration from Slovakia to North America.

"It was a warning because people didn't know what cremation was."

No reflection in society

It is estimated that before World War I, some 650,000 Slovaks emigrated to America.

The museum in the village of Pavlovce nad Uhom, specifically in the part called Ťahyňa, in eastern Slovakia, only a few kilometres from the border with Ukraine, is dedicated to them and their life in the New World. Most people emigrated from this part of the country.

"One-third of the nation emigrated without any reflection in Slovak society," explains Javor, giving the reasons for founding the museum. The aim is to preserve their cultural heritage.

The museum's name, Kasigarda, is a broken English version of Castle Garden, the main immigration office gate in New York, through which every immigrant had to pass.

It is located in an American-style house ("amerikánsky" in Slovak - Ed. note) that was acquired and renovated.

Yes, the museum is in a remote place, but where else would it be appropriate to have it if not here?

In front of the house stands a fence with enamel cups, and a huge cut-down tree trunk with signposts attached to individual branches pointing to the places where Slovaks went. Among them is Iwo Jima, where Michael Strank from the iconic WW2 flag-raising photo died. It is 8,900 kilometres from Ťahyňa.

On the grounds, young trees have been planted by people close to the emigrants.

Mistaking Slovaks for Native Americans

Javor's family was affected by emigration as well.

"My two great-grandmothers were born in America, one in Homestead, Pennsylvania, and the other in Cleveland, Ohio. My two grandfathers died in Chicago and New Jersey. One of my grandmother's estate forms the backbone of the museum," says Javor upon entering the first room, adding that 90 percent of the items are from the United States and Canada. Two museum workers, Katarína Meždejová and Zuzana Koščová, helped with the exposition. In total, the museum has more than 4,000 items.

"My great-grand uncle Michael Javor was at the landing in Guadalcanal, where he earned a Purple Heart," he continues.

One of the things that immediately catch your eye upon entering is the soldier's uniform on a mannequin standing right opposite the entrance, specifically that of an American Slovak in the Štefánik legions.

"His name was Jozef Kacír and he was among the 110 people personally recruited by [Milan Rastislav] Štefánik in America who fought on the French front in WW1," says Javor. It is one of their most precious exhibits.

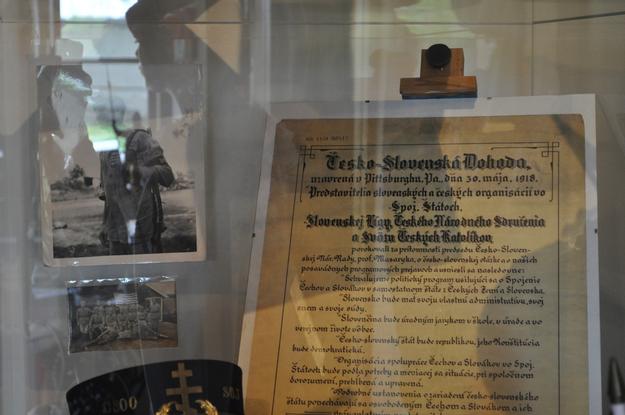

Right next to it stands one of the original copies of the Pittsburgh Agreement in a display case, which prescribed the intent to create an independent Czechoslovakia. The document was salvaged from the closed office of the Slovak League in Passaic, New Jersey.

There are more garments to see. The mannequin to the left displays a skirt and blouse from 1953, sewn in the village of Staré near Michalovce from nylon. The fabric was considered too precious for curtains, for which it was originally intended. The mannequin to the right shows a traditional costume that won the prize for the most beautiful folk dress in 1941 in Cleveland. It originally comes from Heľpa, a village in central Slovakia.

Emigrants from Slovakia to America often arrived in such clothes. Since they were also tanned from summer work, the locals mistook them for Native Americans and shot at them.

Also displayed are a few of the most interesting suitcases, though according to Javor, they have dozens more.

One bears the name of its owner, Alžbeta Horňák, who left from Vrbovce. On the black wood, "Okres Myjava, Czechoslovakia, Europa" is written in white. The back of Javor’s great-grandmother's suitcase reads: "Bodaj by še nám šifra nepotopila", which translates to "May our ship not sink."

They may go unnoticed at first glance, but at the very back of the room sport trophies stand on another suitcase, including one from the 1928 Slovak Baseball League Championship. A proof that Slovaks had no problem assimilating.

"Hundreds of Americans visited the museum and to my surprise, none of them could explain the sport to me," Javor jokes.

Before we move to the next room, the historian points to a collection of seal-making devices. He pulls out a piece of paper and gives me the chance to try it out. Because of what I remember from post offices, I push the handle down very quickly, almost causing the device to fall. The seal on the paper is barely visible.

"You have to do it slowly and firmly," he advises. He rotates the paper, puts it back, slowly pushes the lever and presses. A clear seal imprint appears on the paper.

"When schools visit, they spend hours stamping," he adds.

Confessional life at the centre

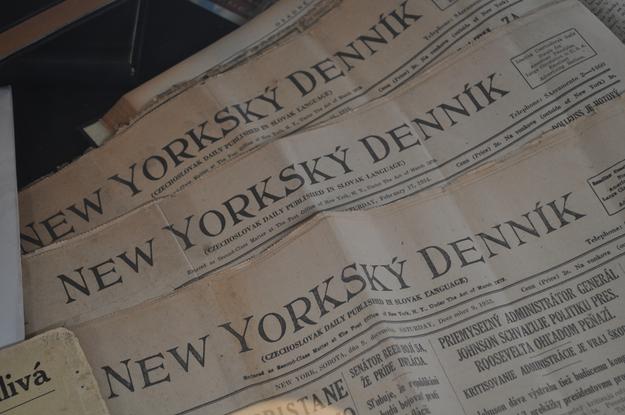

"Slovaks in America published more than 270 types of print materials," Javor says, continuing his explanation in the next room, directing attention to the display case in its centre. This and similar cases were provided for free by the Slovak National Museum, which, according to him, is a great supporter of Kasigarda.

Issues of Jednota (Unity), New Yorkský Denník (New York Daily), Slovenský Sokol (Slovak Falcon), Floridský Slovák (Florida Slovak), and many more are on display.

One thing that definitely catches the eye is a divided canvas painting that dominates the room.

"This painting was probably the most difficult thing to get. It's called Christ and Miners and was painted by Ján Mallin. It's from the Slovak Church of St. Stephen in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania," he tells me.

A pedestal in front of the painting holds a smaller replica that allows you to read the entire inscription. Loosely translated, it reads "Come to me, all you who labour and are burdened, and I will give you rest".

The Kasigarda museum

The website and Facebook page.

Address: Ťahyňská 915/36, 072 14 Pavlovce nad Uhom-Ťahyňa, Slovakia

Book your visit here.

You can visit the museum virtually here.

"By the time I got the painting, someone had cut Christ out of it. Thankfully, I managed to preserve at least a part of it."

The confessional life of Slovaks is also reflected in other exhibits. You will find commemorative plates from Slovak churches in America, totalling 720.

"I am proud that this church was built thanks to my grandmother. This is the first Slovak church in the Western Hemisphere," says Javor, pointing to one of the plates. Above the window, there is a stained glass piece from the Church of St. Michael in Munhall, Pennsylvania. The originally wooden church was later rebuilt by the famous architect John T. Comes. The stained glass reads "Give drink to thirsty." The woman from the opening story also attended this church.

There is also a display case dedicated to Michal Bosák, who became wealthy through the sale of alcohol as well as his banking endeavours - he founded the Bosák State Bank. Another display case features ribbons worn by Slovaks to show their membership in various associations, while another showcases badges supporting politicians and other small items.

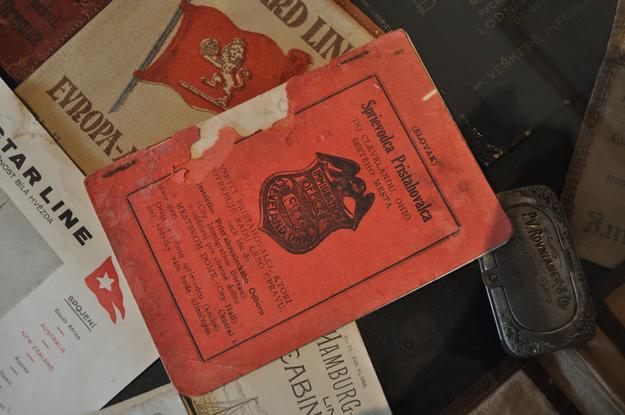

"This immigrant guide to Cleveland is an absolute rarity. It was published in 14 languages, and we have the only surviving Slovak copy. Immigrants received this upon arrival. There is one sentence not found in the English version: 'Do not spit on the ground,'" Javor says.

Rich cultural life

The last room is dedicated to the daily lives of Slovaks in America. The walls are adorned with old photographs: a meeting with President Hoover at the White House, the Slovak Sokol Congress in Connecticut, gymnastics, baseball, basketball, tennis, theatre performances, singing, and dancing.

More proof that Slovaks led a rich cultural life in the US.

Here, you will find a Slovak reader, catechism, and cookbooks with modified recipes because there some of the necessary ingredients were hard to come by in the New World.

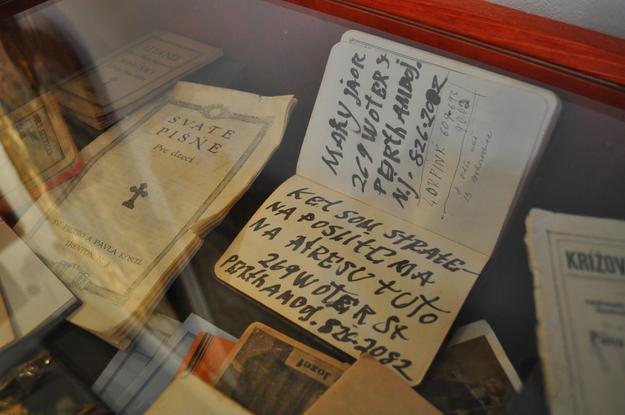

An interesting story is associated with Javor’s great-grandmother's prayer book, which was published in America. On the back, she wrote: "If lost, send me to the address 269 Water Street."

Just two houses down lived the grandmother of musician Jon Bon Jovi, who was Slovak and visited Javor’s great-grandmother, who cooked for her. Bon Jovi acknowledges his Slovak roots, which is confirmed by a signed photograph.

He is not the only one. Next to him is Eugene Cernan's signature, the last man on the Moon, who also had Slovak roots. Construction of an observatory named after him is being planned next to the museum.

"Slovaks need to be reminded of this; that is why this museum exists. To show that these people truly succeeded in their new homeland," adds Javor.

At one point, the historian points to a sign that says "Je Dobre" (It is good) and asks what I think it means. I had no idea; to my surprise, he said that Slovaks in Philadelphia brewed their own beer and named it this.

All these exhibits surround an installation in the centre of the room called "The Trunk of the Transformation of a Slovak into an Amerikán (American)." It shows how a Slovak in traditional dress with a pitchfork transformed into an American in a suit with a pipe through hard work in the mines. The next generation swapped suits for denim clothing, and sent dollars home, which their family exchanged for "bony" (a special currency issued for use at stores during communism - Ed. note) and bought Walkmans, cameras, and other items from the "Tuzex" stores with them. The Americanisation was ultimately completed with a baseball cap, Coca-Cola, and an iPhone.

Spectacular Slovakia travel guides

A helping hand in the heart of Europe thanks to the Slovakia travel guide with more than 1,000 photos and hundred of tourist spots.

Detailed travel guide to the Tatras introduces you to the whole region around the Tatra mountains, including attractions on the Polish side.

Lost in Bratislava? Impossible with our City Guide!

See some selected travel articles, podcasts, and traveller info as well as other guides dedicated to Nitra, Trenčín Region, Trnava Region and Žilina Region.